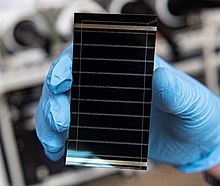

Perovskite solar cell

Perovskite solar cells have found use in powering prototypes of low-power wireless electronics for ambient-powered Internet of things applications,[10] and may help mitigate climate change.

[14] The most commonly studied perovskite absorber is methylammonium lead trihalide (CH3NH3PbX3, where X is a halogen ion such as iodide, bromide, or chloride), which has an optical bandgap between ~1.55 and 2.3 eV, depending on halide content.

However, the metal organic chemical vapor deposition (mocvd) process needed to synthesise lattice-matched and crystalline solar cells with more than one junction is very expensive, making it a less than ideal candidate for widespread use.

Perovskite semiconductors offer an option that has the potential to rival the efficiency of multi-junction solar cells but can be synthesised under more common conditions at a greatly reduced cost.

These multi-junction perovskite solar cells, in addition to being available for cost-effective synthesis, also maintain high PCE under varying weather extremes – making them utilizable worldwide.

[25] This also made them difficult to synthesize at ambient temperatures as the black α-phase is thermodynamically unstable with respect to the yellow δ-phase, although this has been recently tackled by Hei Ming Lai's group, who is a psychiatrist.

[26] The challenge of stabilizing the photoactive black α-phase of inorganic perovskite materials has been tackled in a variety of strategies, including octahedral anchoring and secondary crystal growth.

[31] A study by Tu et al. performed mechanical properties testing on a simple lead iodide system to investigate the role of the number and the length of subunits (organic layer) on the out of plane Young’s modulus utilizing nanoindentation.

Another technique using room temperature solvent-solvent extraction produces high-quality crystalline films with precise control over thickness down to 20 nanometers across areas several centimeters square without generating pinholes.

On one hand, self-assembled porous PbI2 is formed by incorporating small amounts of rationally chosen additives into the PbI2 precursor solutions, which significantly facilitate the conversion of perovskite without any PbI2 residue.

In 2014, Olga Malinkiewicz presented her inkjet printing manufacturing process for perovskite sheets in Boston (US) during the MRS fall meeting – for which she received MIT Technology review's innovators under 35 award.

In contrast to CdTe, hybrid perovskites are very unstable and easily degrade to rather soluble compounds of Pb or Sn with KSP=4.4×10−9, which significantly increases their potential bioavailability[84] and hazard for human health, as confirmed by recent toxicological studies.

[88] Recently, Hong Zhang et al. reported a universal co-solvent dilution strategy to significantly reduce the toxic lead waste production, the usage of perovskite materials as well as the fabrication cost by 70%, which also delivers PCEs of over 24% and 18.45% in labotorary cells and modules, respectively.

[91] Germanium halide perovskites have proven similarly unsuccessful due to low efficiencies and issues with oxidising tendencies, with one experimental solar cells displaying a PCE of only 0.11%.

[95] Experimental results have also shown that, while Antimony and Bismuth halide-based PSCs have good stability, their low carrier mobilities and poor charge transport properties restrict their viability in replacing lead-based perovskites.

This work shows that through judicious selection of a greener co-solvent, we can significantly reduce the usage and waste of toxic solvents and perovskite raw materials, while also simplifying fabrication and cutting costs of PSCs.

[109][110][111][112] Also there have some efforts to cast light on the device mechanism based on simulations where Agrawal et al.[113] suggests a modeling framework,[114] presents analysis of near ideal efficiency, and [115] talks about the importance of interface of perovskite and hole/electron transport layers.

[149] Encapsulating the perovskite absorber with a composite of carbon nanotubes and an inert polymer matrix can prevent the immediate degradation of the material by moist air at elevated temperatures.

[161] However, researchers from EPFL published in June 2017, a work successfully demonstrating large scale perovskite solar modules with no observed degradation over one year (short circuit conditions).

[168] Overall, these ISOS tests helped determine the causes of PSC degradation, which were found to include extended exposure to visible and UV light, environmental contamination, high temperatures, and electrical biases.

But it appears that determining the solar cell efficiency from IV-curves risks producing inflated values if the scanning parameters exceed the time-scale which the perovskite system requires in order to reach an electronic steady-state.

Two possible solutions have been proposed: Unger et al. show that extremely slow voltage-scans allow the system to settle into steady-state conditions at every measurement point which thus eliminates any discrepancy between the FB-SC and the SC-FB scan.

The ambiguity in determining the solar cell efficiency from current-voltage characteristics due to the observed hysteresis has also affected the certification process done by accredited laboratories such as NREL.

Finally, this device served to prove that anions other than iodine and bromine ions are capable of being bombarded into gaps in PV cells, breaking a trend that was evidently hindering prior research [198].

[206] Werner et al. then improved this performance by replacing the SnO2 layer with PCBM and introducing a sequential hybrid deposition method for the perovskite absorber, leading to a tandem cell with 21.2% efficiency.

[211] In March 2020, KAUST-University of Toronto teams reported in Science Magazine regarding tandem devices with spin-cast perovskite films on fully textured bottom cells with 25.7% efficiency.

[220] In addition, making formamidinium cesium lead iodide bromide perovskite into four-terminal tandem cells could achieve efficiency ranging from 19.8% to 25.2%, depending on the parameters of the measurements.

In 2017, Dewei Zhao et al. fabricated low-bandgap (~1.25 eV) mixed Sn-Pb perovskite solar cells (PVSCs) with the thickness of 620 nm, which enables larger grains and higher crystallinity to extend the carrier lifetimes to more than 250 ns, reaching a maximum power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 17.6%.

Furthermore, this low-bandgap PVSC reached an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of more than 70% in the wavelength range of 700–900 nm, the essential infrared spectral region where sunlight transmitted to bottom cell.

This value was measured and recorded by Japan Electrical Safety and Environment Technology Laboratories, and was reached by passivating defects at grain boundaries of the traditional lead-tin perovskite using zwitterionic molecules.