Personal rapid transit

[8] Personal rapid transit systems attempt to eliminate these wastes by moving small groups nonstop in automated vehicles on fixed tracks.

Passengers can ideally board a pod immediately upon arriving at a station, and can – with a sufficiently extensive network of tracks – take relatively direct routes to their destination without stops.

[8][9] The low weight of PRT's small vehicles allows smaller guideways and support structures than mass transit systems like light rail.

Past projects have failed because of financing, cost overruns, regulatory conflicts, political issues, misapplied technology, and flaws in design, engineering or review.

In 1964, Fichter published a book[38] which proposed an automated public transit system for areas of medium to low population density.

Haltom noticed that the time to start and stop a conventional large monorail train, like those of the Wuppertal Schwebebahn, meant that a single line could only support between 20 and 40 vehicles an hour.

[39] Haltom turned his attention to developing a system that could operate with shorter timings, thereby allowing the individual cars to be smaller while preserving the same overall route capacity.

Lacking pollution control systems, the rapid rise in car ownership and the longer trips to and from work were causing significant air quality problems.

However, planners who were aware of the PRT concept were worried that building more systems based on existing technologies would not help the problem, as Fitcher had earlier noted.

CVS was cancelled when Japan's Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport declared it unsafe under existing rail safety regulations, specifically in respect of braking and headway distances.

They created an extensive PRT technology, including a test track, that was considered fully developed by the German government and its safety authorities.

[22] In January 2003, the prototype ULTra ("Urban Light Transport") system in Cardiff, Wales, was certified to carry passengers by the UK Railway Inspectorate on a 1 km (0.6 mi) test track.

[59] In the 2010s the Mexican Western Institute of Technology and Higher Education began research into project LINT ("Lean Intelligent Network Transportation") and built a 1/12 operational scale model.

Other designs use a car for a model, and choose larger vehicles, making it possible to accommodate families with small children, riders with bicycles, disabled passengers with wheelchairs, or a pallet or two of freight.

According to the designer of Skyweb/Taxi2000, J. Edward Anderson, the lightest system uses linear induction motor (LIM) on the vehicle for both propulsion and braking, which also makes manoeuvres consistent regardless of the weather, especially rain or snow.

Several types of guideways have been proposed or implemented, including beams similar to monorails, bridge-like trusses supporting internal tracks, and cables embedded in a roadway.

The Morgantown PRT failed its cost targets because of the steam-heated track required to keep the large channel guideway free of frequent snow and ice.

Computerized control and active electronic braking (of motors) theoretically permit much closer spacing than the two-second headways recommended for cars at speed.

The UK Railway Inspectorate has evaluated the ULTra design and is willing to accept one-second headways, pending successful completion of initial operational tests at more than 2 seconds.

[67] In other jurisdictions, preexisting rail regulations apply to PRT systems (see CVS, above); these typically calculate headways for absolute stopping distances with standing passengers.

PRT vehicles seat fewer passengers than trains and buses, and must offset this by combining higher average speeds, diverse routes, and shorter headways.

Researchers suggest that high capacity PRT (HCPRT) designs could operate safely at half-second headways, which has already been achieved in practice on the Cabintaxi test track in the late 1970s.

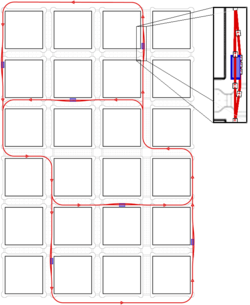

In a PRT system when demand is low, surplus vehicles will be configured to stop at empty stations at strategically placed points around the network.

Early PRT vehicles measured their position by adding up the distance using odometers, with periodic check points to compensate for cumulative errors.

More recent research by the British company ULTra PRT reported that AGT systems have a better safety than more conventional, non-automated modes.

[citation needed] As with many current transit systems, personal passenger safety concerns are likely to be addressed through CCTV monitoring,[76] and communication with a central command center from which engineering or other assistance may be dispatched.

[81] Opponents to PRT schemes have expressed a number of concerns: Vukan R. Vuchic, professor of Transportation Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania and a proponent of traditional forms of transit, has stated his belief that the combination of small vehicles and expensive guideway makes it highly impractical in both cities (not enough capacity) and suburbs (guideway too expensive).

"[83] The manufacturers of ULTra acknowledge that current forms of their system would provide insufficient capacity in high-density areas such as central London, and that the investment costs for the tracks and stations are comparable to building new roads, making the current version of ULTra more suitable for suburbs and other moderate capacity applications, or as a supplementary system in larger cities.

He concluded that there are several issues that would benefit from more research, including urban integration, risks of PRT investment, bad publicity, technical problems, and competing interests from other transport modes.

On the other hand, PRT systems can also make use of self-steering technology and significant benefits remain from operating on a segregated route network.