Transport economics

A single trip (the final good, in the consumer's eyes) may require the bundling of services provided by several firms, agencies and modes.

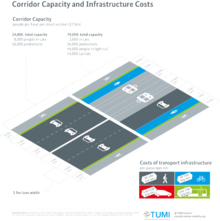

The effect of increases in supply (i.e. capacity) are of particular interest in transport economics (see induced demand), as the potential environmental consequences are significant (see externalities below).

In addition to providing benefits to their users, transport networks impose both positive and negative externalities on non-users.

Positive externalities of transport networks may include the ability to provide emergency services, increases in land value, and agglomeration benefits.

A 2005 American study stated that there are seven root causes of congestion, and gives the following summary of their contributions: bottlenecks 40%, traffic incidents 25%, bad weather 15%, work zones 10%, poor signal timing 5%, and special events/other 5%.

[4] Within the transport economics community, congestion pricing is considered to be an appropriate mechanism to deal with this problem (i.e. to internalise the externality) by allocating scarce roadway capacity to users.

Capacity expansion is also a potential mechanism to deal with traffic congestion, but is often undesirable (particularly in urban areas) and sometimes has questionable benefits (see induced demand).

William Vickrey, winner of the 1996 Nobel Prize for his work on "moral hazard", is considered one of the fathers of congestion pricing, as he first proposed it for the New York City Subway in 1952.

[5] In the road transportation arena these theories were extended by Maurice Allais, a fellow Nobel prize winner "for his pioneering contributions to the theory of markets and efficient utilization of resources", Gabriel Roth who was instrumental in the first designs and upon whose World Bank recommendation[6] the first system was put in place in Singapore.

From 2008 to 2011, Milan had a traffic charge scheme, Ecopass, that exempted higher emission standard vehicles (Euro IV) and other alternative fuel vehicles[17][18][19] This was later replaced by a more conventional congestion pricing scheme, Area C. Even the transport economists who advocate congestion pricing have anticipated several practical limitations, concerns and controversial issues regarding the actual implementation of this policy.

As summarized by noted regional planner Robert Cervero:[20] "True social-cost pricing of metropolitan travel has proven to be a theoretical ideal that so far has eluded real-world implementation.

The primary obstacle is that except for professors of transportation economics and a cadre of vocal environmentalists, few people are in favor of considerably higher charges for peak-period travel.

Critics also argue that charging more to drive is elitist policy, pricing the poor off of roads so that the wealthy can move about unencumbered.

Not everyone will need or want to incur a toll on a daily basis, but on occasions when getting somewhere quickly is necessary, the option of paying to save time is valuable to people at all income levels."

Metropolitan area or city residents, or the taxpayers, will have the option to use the local government-issued mobility rights or congestion credits for themselves, or to trade or sell them to anyone willing to continue traveling by automobile beyond the personal quota.

This trading system will allow direct benefits to be accrued by those users shifting to public transportation or by those reducing their peak-hour travel rather than the government.

The regulation of public transport is often designed to achieve some social, geographic and temporal equity as market forces might otherwise lead to services being limited to the most popular travel times along the most densely settled corridors of development.

The evaluation of projects enables decision makers to understand whether the benefits and costs that were estimated in the appraisal materialised.

The appraisal and evaluation of projects form stages within a broader policy making cycle that includes: In the US those with low income living in cities face a problem called “poverty transportation.” The problem arises because many of the entry-level jobs which are sought out by those with little education are typically located in suburban areas.

And with minimal revenue or funding the transportation systems are forced to decrease service and increase fares, which causes those in poverty to face more inequality.

In places with no public transport a car is the only viable option and that creates unnecessary strain on the roads and environment.

Some of these include creating networks of overlapping routes even among different operators to give people more choice in where and how they want to go somewhere.

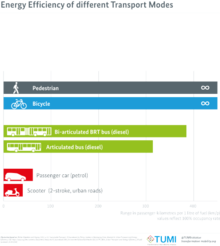

[35] Experiments done in Africa (Uganda and Tanzania) and Sri Lanka on hundreds of households have shown that a bicycle can increase the income of a poor family by as much as 35%.

Taxes can be differentiated to support the market introduction of fuel efficient and low carbon dioxide (CO2) emitting cars.