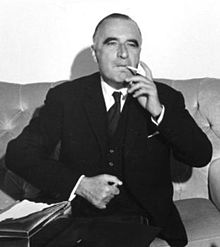

Philibert Tsiranana

[3] To ensure that they won one of the two seats allotted to native people of Madagascar, the inhabitants of the coastal region made an agreement with the Mouvement démocratique de la rénovation malgache (MDRM) which was controlled by the Merina of the uplands.

[3][Note 1] The coastal people agreed to seek the election of Paul Ralaivoavy in the west,[3] while leaving the east to the Merina candidate, Joseph Ravoahangy.

[12] In article published on 24 April 1951 in Varomahery, entitled "Mba Hiraisantsika" (To unite us), he called for reconciliation between the coastal people and the Merina in advance of the forthcoming legislative elections.

[14] The tactic failed because far from creating agreement, it led to suspicion among the coastal political class that he was a communist,[13] and he was forced to renounce his candidature in favour of the "moderate" Raveloson-Mahasampo.

[19] In the same year, Tsiranana joined the new Malagasy Action, a "third party between radical nationalists and supporters of the status quo,"[3] which sought to establish social harmony through equality and justice.

[20] Tsiranana hoped to establish a national profile for himself and transcend the coastal and regional character of PADESM, especially since he no longer supported Madagascar simply being a free state of the French Union, but sought full independence from France.

[3] He rapidly gained a reputation as a frank talker; in March 1956, he affirmed the dissatisfaction of the Malagasy with the French Union which he characterised as simply a continuation of savage colonialism: "All this is just a facade - the foundation remains the same.

As a result, he received harsh criticism from some members of the French Communist Party (PCF) who were allied to ardent nationalists in Tananarive and accused him of seeking to "Balkanise" Madagascar.

[3] This support for private property led him to submit his only bill of law on 20 February 1957, proposing "increased penalties for cattle thieves," which the French penal code did not take into account.

[26] In April 1958, during the 3rd PSD party congress, Tsiranana attacked the Loi Cadre and the bicephalous character which it imposed on the council and the fact that the presidency of the Malagasy government was held by the high commissioner.

A fairly radical opposition existed in the form of the National Movement for the Independence of Madagascar (MONIMA), led by nationalist Monja Jaona who campaigned vigorously on behalf of the very poor Malagasy of the south, while AKFM extolled "scientific socialism" and close friendship with the USSR.

By decree n°60.085 of 24 August 1960 it was established that "the administration of the city of Tananarive is henceforth entrusted to an official chosen by the Minister of the Interior and entitled General Delegate."

[61] According to Tsiranana, the weakness of the opposition was due to the fact that its members "talk a lot but never act," unlike those of the PSD, who were he claimed supported by the majority of Malagasy because they were organised, disciplined, and in permanent contact with the working class.

[70] The economic policy instituted by Tsiranana's administration incorporated a neo-liberal ethos, combining encouragement of (national and foreign) private initiative and state intervention.

We, we need to fill the gaps, because we do not want to create a lazy nationalisation, but on the contrary a dynamic one, which is to say that we must not despoil others and that the state should only intervene where the private sector is deficient.This did not prevent the government from instituting a 50% tax on commercial profits not reinvested in Madagascar.

[92] Membership of this zone allowed Madagascar to assure foreign currency cover for recognised priority imports, to provide a guaranteed market for certain agricultural products (bananas, meat, sugar, de luxe rice, pepper etc.)

[37] In fact, by this French policy, Tsiranana simply tried to extract the maximum amount of profit for his country in the face of the insurmountable constraints against seeking other ways.

[109] In November 1968, a document entitled Dix années de République (Ten Years of the Republic) was published, which had been drafted by a French technical assistant and a Malagasy and which harshly criticised the leaders of PSD, denouncing some financial scandals which the authors attributed to members of the government.

[92] The revision of the Franco-Malagasy accords and significant nationalisation were seen by many Malagasy as offering a way to free up between five and ten thousand jobs, then held by Europeans, which could be replaced by locals.

[122] During this three and a half month period, he received visits from numerous French and Malagasy politicians, including, on 8 April, the head of the opposition, Richard Andriamanjato, who was on his way back from Moscow.

And didn't God take a humble cattle farmer from a lonely village of Madagascar to be head of an entire people?In fact, cut off from reality by an entourage of self-interested courtiers, he showed himself unable to appreciate the socio-economic situation.

[92] On the one side was the moderate, liberal and Christian wing symbolised by Jacques Rabemananjara,[92] which was opposed by the progressivist tendency represented by the powerful minister of the interior, André Resampa.

[129] Some austerity measures and spending cuts concerning cabinet ministers were introduced in September 1965: cancellation of various perks and allowances, including notably the use of administrative vehicles.

[143][144] During the election however, a few journalists had property seized and there was a witchhunt of publications criticising the results of the vote, the methods employed to achieve victory, and the threats and pressure brought to bear on voters in order to get them to the ballot box.

[139] The rebels, led by Monja Jaona, consisted of ranchers from the south-east who refused to pay their heavy taxes and exorbitant mandatory fees to the PSD party.

[146] The exactions of the gendarmerie (whose commander, Colonel Richard Ratsimandrava would later be president in 1975 for six days before his assassination) in response to the insurrection triggered a strong hostility to the "PSD state" across the country.

They had 380 students and student-sympathisers arrested on the evening of 12 May, in order to be imprisoned in the penal colony on Nosy Lava [fr], a small island to the north of Madagascar.

This reconciliation led to the merger of PSD and USM on 10 March 1974, to become the Malagasy Socialist Party (PSM), with Tisranana as president and Resampa as general secretary.

[166] PSM called for a coalition government in order to put an end to economic and social disorder, especially food shortages, linked to the "Malagisation" and "socialisation" of Malagasy society.

In a memorandum of 3 February 1975, Tsiranana proposed the creation of a "committee of elders," which would select a well-known person who would form a provisional government in order to organise free and fair elections within ninety days.