Phillis Wheatley

[2][3] Born in West Africa, she was kidnapped and subsequently sold into slavery at the age of seven or eight and transported to North America, where she was bought by the Wheatley family of Boston.

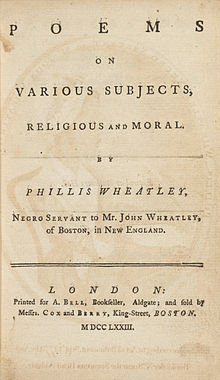

The publication in London of her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral on September 1, 1773, brought her fame both in England and the American colonies.

Although the date and place of her birth are not documented, scholars believe that Wheatley was born in 1753 in West Africa, most likely in present-day Gambia or Senegal.

[7] She was sold by a local chief to a visiting trader, who took her to Boston in the then British Colony of Massachusetts, on July 11, 1761,[8] on a slave ship called The Phillis.

John Wheatley was known as a progressive throughout New England; his family afforded Phillis an unprecedented education for an enslaved person, and one unusual for a woman of any race at the time.

By the age of 12, Phillis was reading Greek and Latin classics in their original languages, as well as difficult passages from the Bible.

[12][13] Recognizing her literary ability, the Wheatley family supported Phillis's education and left household labor to their other domestic enslaved workers.

Strongly influenced by her readings of the works of Alexander Pope, John Milton, Homer, Horace and Virgil, Phillis began to write poetry.

[15] Phillis had an audience with Frederick Bull, who was the Lord Mayor of London, and other prominent members of British society.

Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, became interested in the talented young African woman and subsidized the publication of Wheatley's volume of poems, which appeared in London in the summer of 1773.

[18] Wheatley wrote a letter to Reverend Samson Occom, commending him on his ideas and beliefs stating that enslaved people should be given their natural-born rights in America.

[24] In 1779, Wheatley issued a proposal for a second volume of poems but was unable to publish it because she had lost her patrons after her emancipation; publication of books was often based on gaining subscriptions for guaranteed sales beforehand.

[27] As the American Revolution gained strength, Wheatley's writing turned to themes that expressed ideas of the rebellious colonists.

Her poetry received comment in The London Magazine in 1773, which published her poem "Hymn to the Morning" as a specimen of her work, writing: "[t]hese poems display no astonishing power of genius; but when we consider them as the productions of a young untutored African, who wrote them after six months casual study of the English language and of writing, we cannot suppress our admiration of talents so vigorous and lively.

[40] John C. Shields, noting that her poetry did not simply reflect the literature she read but was based on her personal ideas and beliefs, writes: Wheatley had more in mind than simple conformity.

"[42] Shields believes that the word "light" is significant to her as it marks her African history, a past that she has left physically behind.

[42] Wheatley also refers to "heav'nly muse" in two of her poems: "To a Clergy Man on the Death of his Lady" and "Isaiah LXIII," signifying her idea of the Christian deity.

O'Neal notes that Wheatley "was a strong force among contemporary abolitionist writers, and that, through the use of Biblical imagery, she incorporated anti-slavery statements in her work within the confines of her era and her position as a slave.

"[49] Chernoh Sesay, Jr. sees a trend towards a more balanced view of Wheatley, looking at her "not in twentieth century terms, but instead according to the conditions of the eighteenth century,"[50] and Henry Louis Gates has argued for her rehabilitation, asking "What would happen if we ceased to stereotype Wheatley but, instead, read her, read her with all the resourcefulness that she herself brought to her craft?

Writing in 1974, Eleanor Smith argued that the Wheatley family took interest in her at a young age because of her timid and submissive nature.

John Paul Jones asked a fellow officer to deliver some of his personal writings to "Phillis the African favorite of the Nine (muses) and Apollo.

The Phillis Wheatley Community Center opened in 1920 in Greenville, South Carolina, and in 1924 (spelled "Phyllis") in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Bell Booksellers published Wheatley's first book in September 1773 (8 Aldgate, now the location of the Dorsett City Hotel), the unveiling took place of a commemorative blue plaque honoring her, organized by the Nubian Jak Community Trust and Black History Walks.

[65][66] Wheatley is the subject of a project and play by British-Nigerian writer Ade Solanke entitled Phillis in London, which was showcased at the Greenwich Book Festival in June 2018.

[68] A 30-item collection of material related to Wheatley, including publications from her lifetime containing poems by her, was acquired by the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2023.