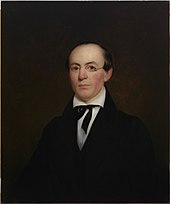

William Lloyd Garrison

He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper The Liberator, which Garrison founded in 1831 and published in Boston until slavery in the United States was partially abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

Garrison promoted "no-governmentism" and rejected the inherent validity of the American government on the basis that its engagement in war, imperialism, and slavery made it corrupt and tyrannical.

He initially opposed violence as a principle and advocated for Christian pacifism against evil; however, at the outbreak of the American Civil War, he recognized the necessity of armed struggle as a means to achieve the abolition of slavery and supported the Lincoln administration’s efforts to end the institution.

He was one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society and promoted immediate and uncompensated, as opposed to gradual and compensated, emancipation of slaves in the United States.

Under An Act for the relief of sick and disabled seamen, his father Abijah Garrison, a merchant-sailing pilot and master, had obtained American papers and moved his family to Newburyport in 1806.

[4] After his apprenticeship ended, Garrison became the sole owner, editor, and printer of the Newburyport Free Press, acquiring the rights from his friend Isaac Knapp, who had also apprenticed at the Herald.

At the age of 25, Garrison joined the anti-slavery movement, later crediting the 1826 book of Presbyterian Reverend John Rankin, Letters on Slavery, for attracting him to the cause.

[5] For a brief time, he became associated with the American Colonization Society, an organization that promoted the "resettlement" of free blacks to a territory (now known as Liberia) on the west coast of Africa.

Although some members of the society encouraged granting freedom to enslaved people, others considered relocation a means to reduce the number of already free blacks in the United States.

[7] In 1829, Garrison began writing for and became co-editor with Benjamin Lundy of the Quaker newspaper Genius of Universal Emancipation, published at that time in Baltimore, Maryland.

Garrison initially shared Lundy's gradualist views, but while working for the Genius, he became convinced of the need to demand immediate and complete emancipation.

The state of Maryland also brought criminal charges[clarification needed] against Garrison, quickly finding him guilty and ordering him to pay a fine of $50 and court costs.

In 1831, Garrison, fully aware of the press as a means to bring about political change,[10]: 750 returned to New England, where he co-founded a weekly anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, with his friend Isaac Knapp.

[11] In the first issue, Garrison stated: In Park-Street Church, on the Fourth of July, 1829, I unreflectingly assented to the popular but pernicious doctrine of gradual abolition.

Although Garrison rejected violence as a means for ending slavery, his critics saw him as a dangerous fanatic because he demanded immediate and total emancipation, without compensation to the slave owners.

A North Carolina grand jury indicted him for distributing incendiary material, and the Georgia Legislature offered a $5,000 reward (equivalent to $152,600 in 2023) for his capture and conveyance to the state for trial.

Later in 1845, when Garrison published a eulogy for his former partner and friend, he revealed that Knapp "was led by adversity and business mismanagement, to put the cup of intoxication to his lips,"[14] forcing the co-authors to part.

After the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery by the Thirteenth Amendment, Garrison published the last issue (number 1,820) on December 29, 1865, writing a "Valedictory" column.

After reviewing his long career in journalism and the cause of abolitionism, he wrote: The object for which the Liberator was commenced – the extermination of chattel slavery – having been gloriously consummated, it seems to be especially appropriate to let its existence cover the historic period of the great struggle; leaving what remains to be done to complete the work of emancipation to other instrumentalities, (of which I hope to avail myself,) under new auspices, with more abundant means, and with millions instead of hundreds for allies.

[18] The mob spotted and apprehended Garrison, tied a rope around his waist, and pulled him through the streets toward Boston Common, calling for tar and feathers.

In 1837, women abolitionists from seven states convened in New York to expand their petitioning efforts and repudiate the social mores that proscribed their participation in public affairs.

In The Liberator Garrison argued that the verdict relied on "circumstantial evidence of the most flimsy character ..." and feared that the determination of the government to uphold its decision to execute Goode was based on race.

[29] On the eve of the Civil War, a sermon preached in a Universalist chapel in Brooklyn, New York, denounced "the bloodthirsty sentiments of Garrison and his school; and did not wonder that the feeling of the South was exasperated, taking as they did, the insane and bloody ravings of the Garrisonian traitors for the fairly expressed opinions of the North.

The resolution prompted a sharp debate, however, led by his long-time friend Wendell Phillips, who argued that the mission of the AASS was not fully completed until black Southerners gained full political and civil equality.

With Wendell Phillips at its head, the AASS continued to operate for five more years, until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution granted voting rights to black men.

[citation needed] In 1870, he became an associate editor of the women's suffrage newspaper, the Woman's Journal, along with Mary Livermore, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Lucy Stone, and Henry B. Blackwell.

[31] In 1873, he healed his long estrangements from Frederick Douglass and Wendell Phillips, affectionately reuniting with them on the platform at an AWSA rally organized by Abby Kelly Foster and Lucy Stone on the one-hundredth anniversary of the Boston Tea Party.

[33] Garrison called the ancient Jews an exclusivist people "whose feet ran to evil" and suggested that the Jewish diaspora was the result of their own "egotism and self-complacency.

"[36][37] However, Garrison acknowledged prejudice against Jews in Europe, which he compared to prejudice against African-Americans, and opposed a proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States affirming the divinity of Jesus Christ on the basis of religious freedom, writing that "no one can fail to see that the Jew, Unitarian, or Deist could not worship in his own way, as an American citizen, precisely because the Constitution, under which his citizenship exists, would make faith in the New Testament and the divinity of Jesus Christ a national creed.

Fanny's son Oswald Garrison Villard became a prominent journalist, a founding member of the NAACP, and wrote an important biography of the abolitionist John Brown.