Philosophy of history

[10][11][verification needed] The divergence between these approaches crystallizes in the disagreements between Hume and Kant on the question of causality.

From the Classical period to the Renaissance, historians' focus alternated between subjects designed to improve mankind and a devotion to fact.

History was composed mainly of hagiographies of monarchs and epic poetry describing heroic deeds such as The Song of Roland—about the Battle of Roncevaux Pass (778) during Charlemagne's first campaign to conquer the Iberian Peninsula.

He introduced a scientific method to the philosophy of history (which Dawood[14] considers something "totally new to his age") and he often referred to it as his "new science", which is now associated with historiography.

His historical method also laid the groundwork for the observation of the role of the state, communication, propaganda, and systematic bias in history.

[13] By the eighteenth century historians had turned toward a more positivist approach—focusing on fact as much as possible, but still with an eye on telling histories that could instruct and improve.

Starting with Fustel de Coulanges (1830–1889) and Theodor Mommsen (1817–1903), historical studies began to move towards a more modern scientific form.

During the Renaissance, cyclical conceptions of history would become common, with proponents illustrating decay and rebirth by pointing to the decline of the Roman Empire.

Condorcet's interpretations of the various "stages of humanity" and Auguste Comte's positivism were among the most important formulations of such conceptions of history, which trusted social progress.

Cyclical conceptions continued in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the works of authors such as Oswald Spengler (1880–1936), Correa Moylan Walsh (1862–1936), Nikolay Danilevsky (1822–1885), Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009),[15] and Paul Kennedy (1945– ), who conceived the human past as a series of repetitive rises and falls.

Spengler, like Butterfield, when writing in reaction to the carnage of the First World War of 1914–1918, believed that a civilization enters upon an era of Caesarism[16] after its soul dies.

[20] John Gaddis has distinguished between exceptional and general causes (following Marc Bloch) and between "routine" and "distinctive links" in causal relationships: "in accounting for what happened at Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, we attach greater importance to the fact that President Truman ordered the dropping of an atomic bomb than to the decision of the Army Air Force to carry out his orders.

Their main point is, however, that such events are rare and that even apparently large shocks like wars and revolutions often have no more than temporary effects on the evolution of the society.

[27][28] Analytic and critical philosophers of history have debated whether historians should express judgements on historical figures, or if this would infringe on their supposed role.

Augustine of Hippo, Thomas Aquinas, Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, in his 1679 Discourse On Universal History, and Gottfried Leibniz, who coined the term, formulated such philosophical theodicies.

Thus, if one adopts God's perspective, seemingly evil events in fact only take place in the larger divine plan.

In this way theodicies explained the necessity of evil as a relative element that forms part of a larger plan of history.

[31] With this end in mind, Hegel applied his philosophical system, both metaphysical and logical, to develop the thesis that the history of humanity consists of a rational process of constant progress towards freedom.

Greece and Rome, civilizations where freedom no longer belonged only to the head of the state, but also to a limited number of people who met certain requirements, that is, the citizens.

[29][34] On the other hand, it is argued that Hegel's philosophy of history is an example of totalitarianism, racism, and Eurocentrism, widely debated criticisms.

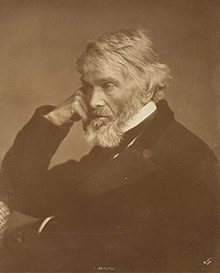

His view of heroes included not only political and military figures, the founders or topplers of states, but artists, poets, theologians and other cultural leaders.

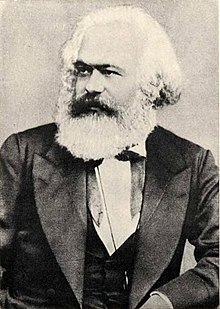

[note 1] After Marx's conception of a materialist history based on the class struggle, which raised attention for the first time to the importance of social factors such as economics in the unfolding of history, Herbert Spencer wrote "You must admit that the genesis of the great man depends on the long series of complex influences which has produced the race in which he appears, and the social state into which that race has slowly grown.

Maine described the direction of progress as "from status to contract," from a world in which a child's whole life is pre-determined by the circumstances of his birth, toward one of mobility and choice.

Historians of the Annales School, founded in 1929 by Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch, were a major landmark in the shift from a history centered on individual subjects to studies concentrating in geography, economics, demography, and other social forces.

History itself, which was traditionally the sovereign's science, the legend of his glorious feats and monument building, ultimately became the discourse of the people, thus a political stake.

Therefore, what became the historical subject must search in history's furor, under the "juridical code's dried blood", the multiple contingencies from which a fragile rationality temporarily finally emerged.

In spite of this, most modern historians such as Barbara Tuchman or David McCullough consider narrative writing important to their approaches.

Louis Mink writes that "the significance of past occurrences is understandable only as they are locatable in the ensemble of interrelationships that can be grasped only in the construction of narrative form" (148).

Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson also analyzes historical understanding this way, and writes that "history is inaccessible to us except in textual form .

Public education has been seen by republican regimes and the Enlightenment as a prerequisite of the masses' progressive emancipation, as conceived by Kant in Was Ist Aufklärung?