Historical materialism

[2] Marx's lifetime collaborator, Friedrich Engels, coined the term "historical materialism" and described it as "that view of the course of history which seeks the ultimate cause and the great moving power of all important historic events in the economic development of society, in the changes in the modes of production and exchange, in the consequent division of society into distinct classes, and in the struggles of these classes against one another.

Marx's view of history was shaped by his engagement with the intellectual and philosophical movement known as the Age of Enlightenment and the profound scientific, political, economic and social transformations that took place in Britain and other parts of Europe in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.

Some philosophers, for example, Vico (1668–1744), Herder (1744–1803) and Hegel (1770–1831), sought to uncover organizing principles of human history in underlying themes, meanings, and directions.

[15] Marx's ideas were also influenced by his reading of Young Hegelian writer Ludwig Feuerbach's 1833 work Geschichte der neuern Philosophie von Bacon von Verulam bis Benedict Spinoza which covered Gassendi's materialist philosophy as well as Gassendi's treatment on materialist Ancient Greek philosophers such as Epicurus, Leucippus, and Democritus.

[15] Inspired by Enlightenment thinkers, especially Condorcet, the utopian socialist Henri de Saint-Simon (1760–1825) formulated his own materialist interpretation of history, similar to those later used in Marxism, analyzing historical epochs based on their level of technology and organization and dividing them between eras of slavery, serfdom, and finally wage labor.

[16][17] According to the socialist leader Jean Jaurès, the French writer Antoine Barnave was the first to develop the theory that economic forces were the driving factors in history.

[18] Marx came to his commitment to a materialist analysis of society and political economy around 1844 and completed his works The Holy Family in 1845, The German Ideology or Leipzig Council in 1846, and The Poverty of Philosophy in 1847 along with Friedrich Engels.

[19] Marx rejected the enlightenment view that ideas alone were the driving force in society or that the underlying cause of change was guided by the actions of leaders in government or religion.

One of Hegel's key critiques of enlightenment philosophy was that while thinkers were often able to describe what made societies from one epoch to the next different, they struggled to account for why they changed.

[23] Hegel challenged this view and argued that human nature as well as the formulations of art, science and the institutions of the state and its codes, laws and norms were all defined by their history and could only be understood by examining their historical development.

[27] It was only through wider society and the state, which was expressed in each historical epoch, by a "spirit of the age", collective consciousness or geist, that "Freedom" could be realized.

[citation needed] These ideas were inspirational to Marx and the Young Hegelians who sought to develop a radical critique of the Prussian authorities and their failure to introduce constitutional change or reform social institutions.

The book is a lengthy polemic against Marx and Engels' fellow Young Hegelians and contemporaries Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, and Max Stirner.

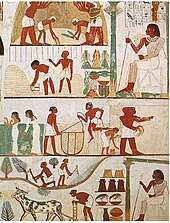

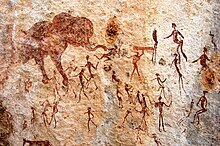

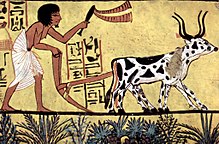

In The German Ideology, Marx wrote that the first historical act was the production of means to satisfy material needs and that labor is a "fundamental condition of all history, which today, as thousands of years ago, must daily and hourly be fulfilled merely in order to sustain human life".

"[42] It is because the influences in the two directions are not symmetrical that it makes sense to speak of primary and secondary factors, even where one is giving a non-reductionist, "holistic" account of social interaction.

Historical materialism posits that history is made as a result of struggle between different social classes rooted in the underlying economic base.

In a primitive communist society, the productive forces would have consisted of all able-bodied persons engaged in obtaining food and resources from the land,[46] and everyone would share in what was produced by hunting and gathering.

The other was expressed in the expansion of links among nations, the breaking down of barriers between them, the establishment of a unified economy and of a world market (globalization); the first is a characteristic of lower-stage capitalism and the second a more advanced form, furthering the unity of the international proletariat.

The Communist Manifesto stated: National differences and antagonism between peoples are daily more and more vanishing, owing to the development of the bourgeoisie, to freedom of commerce, to the world market, to uniformity in the mode of production and in the conditions of life corresponding thereto.

[59]The bourgeoisie, as Marx stated in The Communist Manifesto, has "forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons—the modern working class—the proletarians.

Some such as Joseph Stalin, Fidel Castro, and other Marxist-Leninists believe that the lower-stage of communism constitutes its own mode of production, which they call socialist rather than communist.

[citation needed] The first explicit and systematic summary of the materialist interpretation of history to be published was Engels's book Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science, written with Marx's approval and guidance, and often referred to as the Anti-Dühring.

Towards the end of his life, in 1877, Marx wrote a letter to the editor of the Russian paper Otetchestvennye Zapisky, which significantly contained the following disclaimer: Russia... will not succeed without having first transformed a good part of her peasants into proletarians; and after that, once taken to the bosom of the capitalist regime, she will experience its pitiless laws like other profane peoples.

[72] In a letter to Conrad Schmidt dated 5 August 1890, he stated: And if this man [i.e., Paul Barth] has not yet discovered that while the material mode of existence is the primum agens [first agent] this does not preclude the ideological spheres from reacting upon it in their turn, though with a secondary effect, he cannot possibly have understood the subject he is writing about.

[73]Finally, in a letter to Franz Mehring dated 14 July 1893, Engels stated: [T]here is only one other point lacking, which, however, Marx and I always failed to stress enough in our writings and in regard to which we are all equally guilty.

[77] In his 1940 essay Theses on the Philosophy of History, scholar Walter Benjamin compares historical materialism to the Turk, an 18th-century device which was promoted as a mechanized automaton which could defeat skilled chess players but actually concealed a human who controlled the machine.

"[79] Indeed, in the years after Marx and Engels' deaths, "historical materialism" was identified as a distinct philosophical doctrine and was subsequently elaborated upon and systematized by Orthodox Marxist and Marxist–Leninist thinkers such as Eduard Bernstein, Karl Kautsky, Georgi Plekhanov and Nikolai Bukharin.

[82] Perhaps the most notable recent exploration of historical materialism is G. A. Cohen's Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence,[83] which inaugurated the school of Analytical Marxism.

A major effort to "renew" historical materialism comes from historian Ellen Meiksins Wood, who wrote in 1995 that, "There is something off about the assumption that the collapse of Communism represents a terminal crisis for Marxism.

[89]Referencing Marx's Theses on Feuerbach, Wood argued for historical materialism to be understood as "a theoretical foundation for interpreting the world in order to change it.