Philosophical pessimism

Later thinkers, including Julio Cabrera and David Benatar, have expanded on pessimism with contemporary analyses focusing on the empirical life experiences of living beings rather than on metaphysical principles.

The character of Rust Cohle in the first season of the TV series True Detective embodies a pessimistic worldview, drawing on the works of authors such as Thomas Ligotti, Emil Cioran, and David Benatar.

Notable 20th and 21st authors who espoused philosophically pessimistic views include Emil Cioran,[30] Peter Wessel Zapffe,[31][32] Eugene Thacker,[33] Thomas Ligotti,[18] David Benatar,[11] Drew M. Dalton,[34] and Julio Cabrera.

Since one of the central concepts in Buddhism is that of liberation or nirvana, this highlights the miserable nature of existence — the need to strive for enlightenment through the Noble Eightfold Path emphasizes that life, under this perspective, is characterized by suffering, lack of a permanent self, and the inevitability of change.

He argues that the natural sciences provide the best foundation for understanding existence, revealing that the totality of reality is in fact composed of diverse individual wills, each striving to live while simultaneously and ultimately contributing to the demise and decay of others.

Instead, the overwhelming pain and despair experienced in such an extreme form of solitude underscores the notion that humans constantly require external values and diversions to find meaning in life.

[50]: §146 Blaise Pascal, a French philosopher from the 17th century, also addresses this theme of diversion, suggesting that humans engage in various distractions to avoid confronting the deeper questions of existence and the suffering that accompanies self-awareness.

In his work "Pensées," Pascal argues that people often seek entertainment and social interaction as a means to escape the anxiety and existential dread that arise from an awareness of their finitude.

[11]: 35–36 Similarly, Peter Wessel Zapffe, a Nowergian philosopher from the 20th century, articulates a profound sense of existential despair rooted in the nature of human interests and the limitations of our earthly existence.

[5]: 267 Philipp Mainländer critiques the moral quietism in Schopenhauer's philosophy and early Buddhism, arguing that while these systems alleviate individual suffering, they neglect broader societal injustices.

He supports communism and a "free love movement" (freie Liebe) as essential for a just society — promoting communal ownership and a collective responsibility to renounce the will to life.

[34]: 239–241 [53] Through such a free love movement, Mainländer seeks to redefine sexual and marital relations, liberating individuals from societal constraints which bind them to marriage and procreation, thus allowing them to pursue the path of contemplation, compassion, chastity, and finally the renunciation of being itself through suicide.

Instead, he opted for a collective solution: he believed that life progresses towards greater rationality — culminating in humankind — and that as humans became more educated and more intelligent, they would see through various illusions regarding the abolition of suffering, eventually realizing that the problem lies ultimately in existence itself.

[4]: 191 In his 1942 essay The Myth of Sisyphus, the 20th century French philosopher Albert Camus similarly presents a kind of "heroic pessimism"; that is to say, a perspective that resonates with Nietzsche's affirmation of life, particularly in the face of existential absurdity.

While Nietzsche advocates for an unqualified acceptance of existence through the concepts of amor fati and eternal recurrence, Camus on the other hand makes use of Sisyphus's punishment as a metaphor for the human condition, similarly emphasizing the importance of embracing life, even amidst its inherent struggles and absurdities.

[18]: 181 Peter Wessel Zapffe viewed humans as animals with an overly developed consciousness who yearn for justice and meaning in a fundamentally meaningless and unjust universe — constantly struggling against feelings of existential dread as well as the knowledge of their own mortality.

[31] Sublimation: artistic expression may act as a temporary means of respite from feelings of existential angst by transforming them into works of art that can be aesthetically appreciated from a distance.

[67][68] Thomas Ligotti, an American horror writer, draws parallels between TMT and Zapffe's philosophy, noting that both recognize humans' heightened self-awareness of mortality and the coping mechanisms this awareness necessitates.

Zapffe argues that people shield themselves from existential despair by limiting consciousness, engaging in distractions, and constructing artificial meaning — a view that echoes Becker's analysis of how individuals use social and psychological strategies to manage their fear of death.

[18]: 158–159 Peter Wessel Zapffe was skeptical of many forms of technological enhancements, viewing them primarily as superficial distractions that fail to address the deeper existential questions present in human life.

From Zapffe's perspective, the current human baseline is itself in a "sick" state due to our overly developed awareness towards questions regarding metaphysical meaning and justice within existence, which challenges the traditional distinction between health and enhancement.

Notably, Arthur Schopenhauer asked:[50]: 318–319 One should try to imagine that the act of procreation were neither a need, nor accompanied by sexual pleasure, but instead a matter of pure, rational reflection; could the human race even continue to exist?

Would not everyone, on the contrary, have so much compassion for the coming generation that he would rather spare it the burden of existence, or at least refuse to take it upon himself to cold-bloodedly impose it on them?Schopenhauer also compares life to a debt that's being collected through urgent needs and torturing wants.

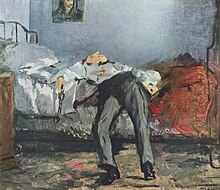

[72]: 584–604 Some pessimists, including David Benatar, Philipp Mainländer and Julio Cabrera, argue that in some extreme situations, such as intense pain, terror, and slavery, people are morally justified to end their own lives.

[12][74][73] Jiwoon Hwang argued that the hedonistic interpretation of David Benatar's axiological asymmetry of harms and benefits entails promortalism — the view that it is always preferable to cease to exist than to continue to live.

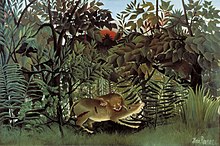

[75] Aside from the human predicament, many philosophical pessimists also emphasize the negative quality of the life of non-human animals and sentient existence as a whole, thereby criticizing the notion of nature as a "wise and benevolent" creator.

He argues that the emotional state of "Weltschmerz"— a pervasive sadness about existence — is not merely a philosophical stance but is deeply influenced by individual psychological traits and socioeconomic conditions.

[91] He identifies several psychological traits that contribute to a pessimistic outlook, including acute sensibility, which leads to an excessive anticipation of suffering; an irritable and rebellious mindset that perceives the world as hostile; a sluggish temperament that fosters a burdensome view of life; a carping disposition that highlights the world's deficiencies compared to personal ideals; and a desire for adulation, which reinforces pessimistic beliefs by seeking recognition as a martyr for enduring suffering.

Russell characterized pessimism as a matter of temperament rather than reason,[92]: 758 while Magee suggested that Schopenhauer's despairing worldview could be seen as neurotic manifestations rooted in his relationship with his mother rather than a coherent philosophical argument.

In contrast, Nietzsche introduces the concept of the "will to power," which he sees as the fundamental driving force in human beings, emphasizing the transcendence and perfection of oneself rather than mere survival.