Phosphatodraco

[1][2] The pterosaur material, catalogued as specimen OCP DEK/GE 111, consists of five disarticulated but closely associated cervical (neck) vertebrae and an indeterminate bone, most likely belonging to a single individual.

Tethydraco was originally considered a pteranodontid, but Labita and Martill concluded it was an azhdarchid, and that it possibly represented the wing elements of Phosphatodraco.

They considered the sideways expansion at the front of this vertebra to be due to crushing, and pointed out that such preservation where fragile, yet well-preserved bones are associated with damaged material of the same individual is known from other vertebrate fossils in the same level.

[1] In 2007, paleontologist Alexander W. A. Kellner and colleagues noted that Phosphatodraco was one of the most interesting azhdarchids found in Africa, but used cautious language about the original interpretation of the vertebrae.

[14] A 2015 article by paleontologist Mátyás Vremir and colleagues called the issue "controversial" and considered the specimen too crushed for proper comparison,[15] and Martill and Markus Moser concurred with this in 2018.

[18] Though the palaeontologist Alexandru A. Solomon and colleagues noted the suggested change in interpretation of the holotype order in 2019, they stated that even if the reinterpretation was correct, the specimen was too damaged for comparison with the single known cervical vertebra of their new genus Albadraco.

Combined, the long-wing metacarpals and legs made azhdarchids relatively taller when standing than other pterosaurs, though their feet were narrow and short.

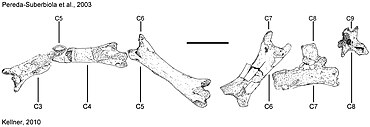

The vertebrae vary in length, the longest being the frontmost of those preserved, a C5 broken in two according to Pereda-Suberbiola and colleagues (C3–C4 according to Kellner[10]), which they estimated to have been about 300 mm (0.98 ft) long when complete.

The right prezygapophys has a small tubercle (a rounded projection) at the midline, and there is no indication of additional processes at the front end of the vertebra or pneumatic foramina (holes) on the side surface of the centrum.

A small protuberance between the postzygapophyses perhaps indicates where the upper margin of the neural canal (through which the spinal cord passed) was located, though its features cannot be accurately determined.

The front and hind margins of the neural spine are vertically parallel to each other, and its top is truncated in a square shape, and perpendicular to the side edges.

[1] In their 2003 description Pereda-Suberbiola and colleagues considered Phosphatodraco a member of Azhdarchidae based on features such as its mid-series cervical vertebrae being elongated, with low vestigial (almost evolutionarily lost) or absent neural spines, the presence of prezygapophyseal tubercles, a pair of lower sulci near the prezygapophyses, and the lack of oval pneumatic foramina on the lower surfaces of the centra.

These researchers noted that previous studies had defined Azhdarchidae as a node-based clade with Azhdarcho and Quetzalcoatlus as internal specifiers, but cautioned that in their new phylogeny, Phosphatodraco, Zhejiangopterus, and Eurazhdarcho would fall outside the group.

They found this undesirable, as those genera had otherwise consistently been considered azhdarchids, and that for stability's sake, Phosphatodraco should be added as a third internal specifier for the group, since this would result in all these taxa being included.

[18] In 2021, American paleontologist Brian Andres also found Phosphatodraco and Aralazhdarcho to be sister taxa, supported by the reduction of pneumatic foramina on the side of the neural canal.

[23] In a 2022 phylogenetic analysis by Argentinian paleontologist Leonardo Ortiz David and colleagues, Phosphatodraco and Aralazhdarcho were again recovered as sister taxa, corroborating their close relationship that is based on similar features.

However, unlike Andres in 2021, Ortiz David and colleagues found both pterosaurs outside Quetzalcoatlinae, in a more basal (primitive) position within Azhdarchidae, forming a clade with Eurazhdarcho.

Eurazhdarcho langendorfensis Phosphatodraco mauritanicus Aralazhdarcho bostobensis Zhejiangopterus linhaiensis Azhdarcho lancicollis Arambourgiania philadelphiae Aerotitan sudamericanus Mistralazhdarcho maggii Hatzegopteryx thambema Albadraco tharmisensis Cryodrakon boreas Thanatosdrakon amaru Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni aff.

In 2008, Witton and Naish pointed out that although azhdarchids have historically been considered to have been scavengers, probers of sediment, swimmers, waders, aerial predators, or stork-like generalists, most researchers until that point had considered them to have been skim-feeders living in coastal settings, which fed by trawling their lower jaws through water while flying and catching prey from the surface (like skimmers and some terns).

In general, pterosaurs have historically been considered marine piscivores (fish-eaters), and despite their unusual anatomy, azhdarchids have been assumed to have occupied the same ecological niche.

[6][2] Witton elaborated in a 2013 book that the proportions of azhdarchids would have been consistent with them striding through vegetated areas with their long limbs, and their downturned skull and jaws reaching the ground.

Their long, stiffened necks would be an advantage as it would help lowering and raising the head and give it a vantage point when searching for prey, and enable them to grab small animals and fruit.

They noted that no azhdarchids had been found in truly terrestrial strata, and proposed they could instead have been associated with aquatic environments, such as rivers, lakes, marine and off-shore settings.

Pterosaurs during this time thereby had increased niche-partitioning compared to earlier faunas from the Santonian and Campanian ages, and they were able to outcompete birds in large size based niches, and birds therefore remained small, not exceeding 2 m (6.6 ft) wingspans during the Late Cretaceous (most pterosaurs during this time had larger wingspans, and thereby avoided the small-size niche).

Albatross-like soaring has also been suggested, but Witton thought this unlikely due to the supposed terrestrial bias of their fossils and adaptations for foraging on the ground.

Studies of azhdarchid flight abilities indicate they would have been able to fly for long and probably fast (especially if they had an adequate amount of fat and muscle as nourishment), so that geographical barriers would not present obstacles.

One long trackway of this kind shows that azhdarchids walked with their limbs held directly underneath their body, and along with the morphology of their feet indicates they were more proficient on the ground than other pterosaurs.

[1][2] The kind of fossils that are usually used in biostratigraphy are rare, which complicates attempts at dating these beds, but "couche III" has been correlated with the late Maastrichtian on the basis of shark teeth, which has also been confirmed by carbon and oxygen isotope stratigraphy.

[2] The phosphatic matrix of the original Phosphatodraco specimen is gray and mottled with orange, and contained fossils including of the fish Serratolamna, Rhombodus, and Enchodus, and the mosasaur Prognathodon, as well as small nodules.

Longrich and colleagues suggested in 2018 that, although the fauna was overwhelmingly marine, the presence of terrestrial dinosaurs and azhdarchids indicates the coast was nearby.