Piano Sonata No. 29 (Beethoven)

[5] Amongst the sketches for the first movement is an idea for an abandoned cantata for Archduke Rudolph, using the text 'Vivat Rudolphus' and a melody resembling that of the 'Hammerklavier' sonata.

This intention was confirmed in a letter dated 3 March 1819, in which Beethoven wrote that the sonata had long been 'wholly intended in my heart' for the archduke.

[7] Musicologist William Kinderman attributed this to his preoccupation with his nephew Karl van Beethoven, his health problems,[1] and an increasing focus on each of his major new compositions, usually large-scale works.

[12] The reason for this rearrangement was purely economical, as Charles Rosen believed Beethoven's sole concern for publishing the sonata in London was to obtain additional financial benefit.

[18] In addition to the thematic connections within the movements and the use of traditional Classical formal structures, Charles Rosen has described how much of the piece is organised around the motif of a descending third (major or minor).

[15] This descending third is quite ubiquitous throughout the work but most clearly recognizable in the following sections: the opening fanfare of the Allegro; in the scherzo's imitation of the aforementioned fanfare, as well as in its trio theme; in bar two of the adagio; and in the fugue in both its introductory bass octave-patterns and in the main subject, as the seven-note runs which end up on notes descended by thirds.

[20] The metronome mark was given at the beginning of a letter to Ferdinand Ries, dated 16 April 1819, that states the tempo of 138 BPM on the half note for the first movement.

[21] This is considered so fast that it is routinely dismissed by performers based on theories that it was caused by a mistake from the composer, a faulty metronome, or Beethoven's deafness.

The exposition ends with a largely stepwise figure in the treble clef in a high register, while the left hand moves in an octave-outlining accompaniment in eighth notes.

The retransition is brought about by a sequence of rising intervals that get progressively higher, until the first theme is stated again in the home key of B♭, signalling the beginning of the recapitulation.

The coda repetitively cites motives from the opening statement over a shimmering pedal point and disappears into pianississimo until two fortissimo B♭ major chords conclude the movement.

Following this dark interlude, Beethoven inserts a more intense presto section in 24 meter, still in B♭ minor,[31] which eventually segues back to the scherzo, marked "dolce".

[37] Structurally, it follows traditional Classical-era sonata form, but the recapitulation of the main theme is varied to include extensive figurations in the right hand that anticipate some of the techniques of Romantic piano music.

NPR's Ted Libbey writes, "An entire line of development in Romantic music—passing through Schubert, Chopin, Schumann, Brahms, and even Liszt—springs from this music.

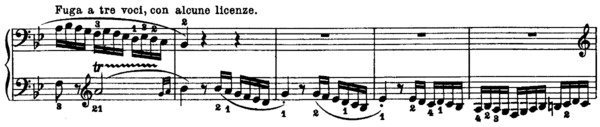

[40] The subject of the fugue can be divided itself into three parts: a tenth leap followed by a trill to the tonic; a 7-note scale figure repeated descending by a third; and a tail semiquaver passage marked by many chromatic passing tones, whose development becomes the main source for the movement's unique dissonance.

Marked con alcune licenze ("with some licenses"), the fugue, one of Beethoven's greatest contrapuntal achievements, as well as making tremendous demands on the performer, moves through a number of contrasting sections and includes a number of "learned" contrapuntal devices, often, and significantly, wielded with a dramatic fury and dissonance inimical to their conservative and academic associations.

In such cases, the artist coming after should try to correct the great men's lives after the fact; for example, a master of all orchestral effects would do so by restoring to life the symphony that had suffered an apparent pianistic death.