Piano Sonata No. 31 (Beethoven)

The Allegro second movement begins with a terse but humorous scherzo, which Martin Cooper believes is based on two folk songs, followed by a trio section.

The sonata is the subject of musical analyses including studies by Donald Tovey, Denis Matthews, Heinrich Schenker, and Charles Rosen.

[3] The composer was prevented from completing the promised sonatas on schedule by several factors, including his work on the Missa solemnis (Op.

The sonata's completed autograph score bears the date 25 December 1821, but Beethoven continued to revise the last movement and did not finish until early 1822.

The sonata was published simultaneously in Paris and Berlin that year, and it was announced in the Bibliographie de la France on 14 September.

[10] Alfred Brendel characterises the main themes of the sonata as all derived from the hexachord – the first six notes of the diatonic scale – and the intervals of the third and fourth that divide it.

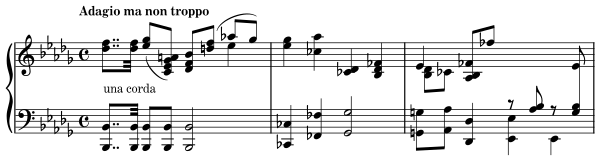

[18] The first movement in A♭ major is marked Moderato cantabile molto espressivo ("at a moderate speed, in a singing style, very expressively").

The second group of themes in the dominant E♭ includes appoggiatura figures, and a bass which descends in steps from E♭ to G three times while the melody rises by a sixth.

[23] The development section (which Rosen calls "radically simple"[21]) consists of restatements of the movement's initial theme in a falling sequence, with underlying semiquaver figures.

[24] The recapitulation begins conventionally with a restatement of the opening theme in the tonic (A♭ major), Beethoven combining it with the arpeggiated transition motif.

Martin Cooper finds that Beethoven indulged the rougher side of his humour in the scherzo by using motifs from two folk songs, "Unsa kätz häd kaz'ln g'habt" ("Our cat has had kittens") and "Ich bin lüderlich, du bist lüderlich" ("I am a draggle-tail, you are a draggle-tail").

[30] Tovey earlier decided that such theories of the themes' origins were "unscrupulous", since the first of these folk songs was arranged by Beethoven some time before this work's composition in payment for a publisher's trifling postage charge – the nature of the arrangement making it clear that the folk songs were of little importance to the composer.

After a few syncopated chords the movement's short coda comes to rest in F major (a Picardy third) via a long broken arpeggio in the bass.

[35] This then leads to an A♭ minor arioso dolente, a lament whose initial melodic contour is similar to the opening of the scherzo (although Tovey dismisses this as insignificant).

[38] Commentators (including Kinderman and Rosen) have seen the initial recitative and arioso as "operatic",[28][35] and Brendel writes that the lament resembles the aria "Es ist vollbracht" (It is finished) from Bach's St John Passion.

[40] The arioso leads into a three-voice fugue in A♭ major, whose subject is constructed from three parallel rising fourths separated by two falling thirds (see below).

[45] Kinderman contrasts the perceived "earthly pain" of the lament with the "consolation and inward strength" of the fugue[43] – which Tovey points out had not reached a conclusion.

[51] Brendel views the section that follows as a "[shaking] off" of the constraints of polyphony;[39] Tovey labels it a "peroration", calling the passage "exultant".

[53] Matthews writes that it is not fanciful to see the final movement's second fugue as a "gathering of confidence after illness or despair",[45] a theme which can be discerned in other late works by Beethoven (Brendel compares it with the Cavatina from the String Quartet No.

[39] Martin Cooper describes the coda as "passionate" and "heroic", but not out of place after the ariosos' distress or the fugues' "luminous verities".

[54] Rosen states that this movement is the first time in the history of music where the academic devices of counterpoint and fugue are integral to a composition's drama, and observes that Beethoven in this work does not "simply symbolize or represent the return to life, but persuades us physically of the process".

109–111 sonatas wrote in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung that contemporary opposition against Beethoven's works "had only small, fleeting success".

"[57] In the 1860 edition of his biography of Beethoven, Anton Schindler wrote that the fugue "is not difficult to play but is full of charm and beauty.

[28] When writing about the sonata in 1909, Hermann Wetzel observed, "Not a single note is superfluous, and there is no passage ... that can be treated as you please, no trivial ornament".

110: "In none of the other 31 piano sonatas does Beethoven cover as much emotional territory: it goes from the absolute depths of despair to utter euphoria ... it is unbelievably compact given its emotional richness, and its philosophical opening idea acts as the work’s thesis statement, permeating the work, and reaching its apotheosis in its final moments.

110 was recorded by Wilhelm Kempff in 1951,[64] Claudio Arrau in 1965,[65] Alfred Brendel in 1973,[66] Maurizio Pollini in 1975,[67] Daniel Barenboim in 1984,[68] and Igor Levit in 2019.