Piano acoustics

Given two strings, equally taut and heavy, one twice as long as the other, the longer will vibrate with a pitch one octave lower than the shorter.

When the overtones are integer multiples (e.g., 2×, 3× ... 6× ... ) of the fundamental frequency (called harmonics), then — neglecting damping — the oscillation is periodic, i.e. it vibrates exactly the same way over and over.

Only when the bending force is much smaller than the tension of the string, are its wave-speed (and the overtones pitched as harmonics) unchanged.

If string diameter, tension, mass, uniformity, and length compromises were the only factors—all pianos could be small, spinet-sized instruments.

Piano builders, however, have found that longer strings increase instrument power, harmonicity, and reverberation, and help produce a properly tempered tuning scale.

Inharmonicity increases continuously as notes get further from the middle of the piano, and is one of the practical limits on the total range of the instrument.

The designer of a short piano is forced to use thick strings to increase mass density and is thus driven into accepting greater inharmonicity.

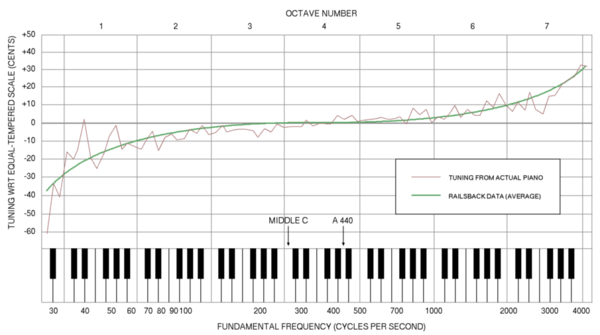

Railsback, a US college physics teacher, expresses the difference between inharmonicity-aware stretched piano tuning, and theoretically correct equal-tempered tuning in which the frequencies of successive notes are related by a constant ratio, equal to the twelfth root of two.

The curve is derived empirically from actual pianos tuned to be pleasing to the ear, not from an exact mathematical equation.

Railsback discovered that pianos were typically tuned in this manner not because of a lack of precision, but because of inharmonicity in the strings.

That stiffness is the result of piano wire's inherent hardness and ductility, together with string tension, thickness, and length.

It is a common misconception that the Railsback curve demonstrates that the middle of the piano is less inharmonic than the upper and lower regions.

[3] As expected, the graph of the actual tuning is not a smooth curve, but a jagged line with peaks and troughs.

This might be the result of imprecise tuning, inexact measurement, or the piano's innate variability in string scaling.