Short octave

In contrast, low C and D, both roots of very common chords, are sorely missed if a harpsichord with lowest key E is tuned to match the keyboard layout.

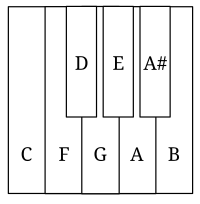

When scholars specify the pitch range of instruments with this kind of short octave, they write "C/E", meaning that the lowest note is a C, played on a key that normally would sound E. A second type of short octave used the keys to play the G major scale Here, the exotic bass notes C♯ and D♯ are sacrificed to obtain the more essential G and A.

The 18th-century author Quirinus van Blankenburg suggested that the C/E short octave originated as an extension of keyboards that went down only to F; the addition of just one key (nominal E) and the reassignment of the F♯ and G♯ added three new notes to the bass range.

[2] Edward Kottick notes that the short octave persisted for a long time, suggests that a kind of mutual inertia between composers and instrument builders may have been responsible: Our forebears were much more practical than we are.

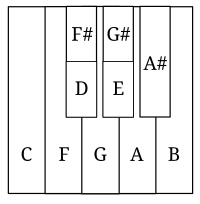

Gerlach (2007) describes this keyboard arrangement as follows: The notes leading down to F1 were accommodated on the keys of a "short-scaled octave" from c to C (only F♯1 and G♯1, as well as C♯ and E♭ continued to be omitted.

[6] The assignment of notes to keys, which strikingly included a triple-split key, was as shown in the following diagram, adapted from (Maunder 1998): Richard Maunder (who uses the term "multiple-broken short octave") observes that the Viennese bass octave, like its predecessors, imposed distortions on the string scaling of the harpsichord: it "leads to extreme foreshortening of the scale in the bass."

[8] While the short octave seems primarily to have been an economy measure, it does have the advantage that the player's left hand can in certain cases span a greater number of notes.

"[a] A later composer who wrote music conveniently playable only on a broken-octave instrument was Joseph Haydn, whose early work for keyboard was intended for harpsichord, not piano.

[6] As Gerlach (2007) points out, Haydn's "Capriccio in G on the folk song 'Acht Sauschneider müssen sein'", H. XVII:1 (1765) is evidently written for a harpsichord employing the Viennese bass octave.

On orthodox keyboards this would be an impossible stretch for most players, but as on the Viennese bass octave it would have been easy to play, with the fingers depressing keys that visually appeared as D–G–B (see diagram above).