Picatrix

Picatrix is the Latin name used today for a 400-page book of magic and astrology originally written in Arabic under the title Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm (Arabic: غاية الحكيم), or Ghayat al-hakim wa-ahaqq al-natijatayn bi-altaqdim[1] which most scholars assume was originally written in the middle of the 11th century,[2] though an argument for composition in the first half of the 10th century has been made.

[5] Another researcher summarizes it as "the most thorough exposition of celestial magic in Arabic", indicating the sources for the work as "Arabic texts on Hermeticism, Sabianism, Ismailism, astrology, alchemy and magic produced in the Near East in the ninth and tenth centuries A.D."[6] Eugenio Garin declares, "In reality the Latin version of the Picatrix is as indispensable as the Corpus Hermeticum or the writings of Albumasar for understanding a conspicuous part of the production of the Renaissance, including the figurative arts.

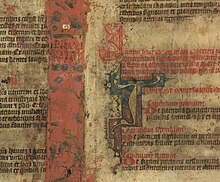

The manuscript in the British Library passed through several hands: Simon Forman, Richard Napier, Elias Ashmole and William Lilly.

Jean Seznec observed, "Picatrix prescribes propitious times and places and the attitude and gestures of the suppliant; he also indicates what terms must be used in petitioning the stars."

I conjure thee, O Supreme Father, by Thy great benevolence and Thy generous bounty, to do for me what I ask [...][10]According to Garin: The work's point of departure is the unity of reality divided into symmetrical and corresponding degrees, planes or worlds: a reality stretched between two poles: the original One, God the source of all existence, and man, the microcosm, who, with his science (scientia) brings the dispersion back to its origin, identifying and using their correspondences.

Scholem also specifically noted Henry Corbin's work in documenting the concept of the perfected nature in Iranian and Islamic religion.

[18] According to Scholem, the following passage from the Picatrix (itself similar to a passage in an earlier Hermetic text called the Secret of Creation) tracks very closely with the Kabbalistic concept of tselem:[19] When I wished to find knowledge of the secrets of Creation, I came upon a dark vault within the depths of the earth, filled with blowing winds.

... Then there appeared to me in my sleep a shape of most wondrous beauty [giving me instructions how to conduct myself in order to attain knowledge of the highest things].

Moreover, the author states that he started writing the Picatrix after he completed his previous book, Rutbat al-Ḥakīm رتبة الحكيم in 343 AH (~ 954 CE).

[23] More recent attributions of authorship range from "the Arabic version is anonymous" to reiterations of the old claim that the author is "the celebrated astronomer and mathematician Abu l-Qasim Maslama b. Ahmad Al-Majriti".

[24] One recent study in Studia Islamica suggests that the authorship of this work should be attributed to Maslama b. Qasim al-Qurtubi, who died 964 CE (353 AH) and, according to Ibn al-Faradi, was "a man of charms and talismans".

"[33] Martin Plessner suggests that a translator of the Picatrix established a medieval definition of scientific experiment by changing a passage in the Hebrew translation of the Arabic original, establishing a theoretical basis for the experimental method: "the invention of an hypothesis in order to explain a certain natural process, then the arranging of conditions under which that process may intentionally be brought about in accordance with the hypothesis, and finally, the justification or refutation of the hypothesis, depending on the outcome of the experiment".Plessner notes that it is generally agreed that awareness of "the specific nature of the experimental method—as distinct from the practical use of it—is an achievement of the 16th and 17th centuries."

However, as the passage by the translator of the Hebrew version makes clear, the fundamental theoretical basis for the experimental method was here established prior to the middle of the 13th century.