Grimoire

[3] While the term grimoire is originally European—and many Europeans throughout history, particularly ceremonial magicians and cunning folk, have used grimoires—the historian Owen Davies has noted that similar books can be found all around the world, ranging from Jamaica to Sumatra.

In the 19th century, with the increasing interest in occultism among the British following the publication of Francis Barrett's The Magus (1801), the term entered English in reference to books of magic.

[1] The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), where they have been found inscribed on cuneiform clay tablets that archaeologists excavated from the city of Uruk and dated to between the 5th and 4th centuries BC.

This likely had an influence upon books of magic, with the trend on known incantations switching from simple health and protection charms to more specific things, such as financial success and sexual fulfillment.

The 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian Josephus mentioned a book circulating under the name of Solomon that contained incantations for summoning demons and described how a Jew called Eleazar used it to cure cases of possession.

The work tells of the building of The Temple and relates that construction was hampered by demons until the archangel Michael gave the King a magical ring.

Solomon used it to lock demons in jars and commanded others to do his bidding, although eventually, according to the Testament, he was tempted into worshiping "false gods", such as Moloch, Baal, and Rapha.

The New Testament records that after the unsuccessful exorcism by the seven sons of Sceva became known, many converts decided to burn their own magic and pagan books in the city of Ephesus; this advice was adopted on a large scale after the Christian ascent to power.

As the historian Owen Davies noted, "while the [Christian] Church was ultimately successful in defeating pagan worship it never managed to demarcate clearly and maintain a line of practice between religious devotion and magic.

[15] The former was acceptable because it was viewed as merely taking note of the powers in nature that were created by God; for instance, the Anglo-Saxon leechbooks, which contained simple spells for medicinal purposes, were tolerated.

[21] Similarly, it was commonly believed by medieval people that other ancient figures, such as the poet Virgil, astronomer Ptolemy, and philosopher Aristotle, had been involved in magic, and grimoires claiming to have been written by them were circulated.

[22] However, there were those who did not believe this; for instance, the Franciscan friar Roger Bacon (c. 1214–94) stated that books falsely claiming to be by ancient authors "ought to be prohibited by law.

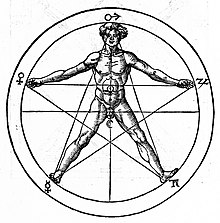

[25] A similar figure was the Swiss magician known as Paracelsus (1493–1541), who published Of the Supreme Mysteries of Nature, in which he emphasised the distinction between good and bad magic.

[26] A third such individual was Johann Georg Faust, upon whom several pieces of later literature were written, such as Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, that portrayed him as consulting with demons.

[29] Alongside these demonological works, grimoires on natural magic continued to be produced, including Magia Naturalis, written by Giambattista Della Porta (1535–1615).

[30] Iceland held magical traditions in regional work as well, most remarkably the Galdrabók, where numerous symbols of mystic origin are dedicated to the practitioner.

These pieces give a perfect fusion of Germanic pagan and Christian influence, seeking splendid help from the Norse gods and referring to the titles of demons.

Despite the advent of print, however, handwritten grimoires remained highly valued, as they were believed to contain inherent magical powers, and they continued to be produced.

[36] In 1599, the church published the Indexes of Prohibited Books, in which many grimoires were listed as forbidden, including several mediaeval ones, such as the Key of Solomon, which were still popular.

Governments tried to crack down on magicians and fortune tellers, particularly in France, where the police viewed them as social pests who took money from the gullible, often in a search for treasure.

The Petit Albert contained a wide variety of magic; for instance, dealing in simple charms for ailments, along with more complex things, such as the instructions for making a Hand of Glory.

The Black Pullet, probably authored in late-18th-century Rome or France, differs from the typical grimoires in that it does not claim to be a manuscript from antiquity, but told by a man who was a member of Napoleon's armed expeditionary forces in Egypt.

Perhaps the most notable of these was the Protestant pastor Georg Conrad Horst (1779–1832) who, from 1821 to 1826, published a six-volume collection of magical texts in which he studied grimoires as a peculiarity of the Medieval mindset.

[52] In the late 19th century, several of these texts (including The Book of Abramelin and the Key of Solomon) were reclaimed by para-Masonic magical organisations, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and Ordo Templi Orientis.

[55] The term grimoire commonly serves as an alternative name for a spell book or tome of magical knowledge in fantasy fiction and role-playing games.