Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

His mainstream scientific achievements include his palaeontological research in China, taking part in the discovery of the significant Peking Man fossils from the Zhoukoudian cave complex near Beijing.

He inherited the double surname from his father, who was descended on the Teilhard side from an ancient family of magistrates from Auvergne originating in Murat, Cantal, ennobled under Louis XVIII of France.

At that time he read Creative Evolution by Henri Bergson, about which he wrote that "the only effect that brilliant book had upon me was to provide fuel at just the right moment, and very briefly, for a fire that was already consuming my heart and mind.

In 1922, with the support of the Catholic Church and the French Concession, Licent built a special building for the museum on the land adjacent to the Tsin Ku University, which was founded by the Jesuits in China.

Many of the publications and writings of the museum and its related institute were included in the world's database of zoological, botanical, and palaeontological literature, which is still an important basis for examining the early scientific records of the various disciplines of biology in northern China.

At this site, the scientists discovered the so-called Peking man (Sinanthropus pekinensis), a fossil hominid dating back at least 350,000 years, which is part of the Homo erectus phase of human evolution.

[17] John Allen Grim, the co-founder and co-director of the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology, said: "I think you have to distinguish between the hundreds of papers that Teilhard wrote in a purely scientific vein, about which there is no controversy.

Two theological essays on original sin were sent to a theologian at his request on a purely personal basis: The Church required him to give up his lecturing at the Catholic Institute in order to continue his geological research in China.

He joined the ongoing excavations of the Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian as an advisor in 1926 and continued in the role for the Cenozoic Research Laboratory of the China Geological Survey following its founding in 1928.

Teilhard resided in Manchuria with Émile Licent, staying in western Shanxi and northern Shaanxi with the Chinese paleontologist Yang Zhongjian and with Davidson Black, Chairman of the China Geological Survey.

Answering an invitation from Henry de Monfreid, Teilhard undertook a journey of two months in Obock, in Harar in the Ethiopian Empire, and in Somalia with his colleague Pierre Lamarre, a geologist,[22] before embarking in Djibouti to return to Tianjin.

Professor von Koenigswald had also found a tooth in a Chinese apothecary shop in 1934 that he believed belonged to a three-meter-tall ape, Gigantopithecus, which lived between one hundred thousand and around a million years ago.

[24] In 1937, Teilhard wrote Le Phénomène spirituel (The Phenomenon of the Spirit) on board the boat Empress of Japan, where he met Sylvia Brett, Ranee of Sarawak[25] The ship took him to the United States.

A decree of the Holy Office dated 30 June 1962, under the authority of Pope John XXIII, warned: [I]t is obvious that in philosophical and theological matters, the said works [Teilhard's] are replete with ambiguities or rather with serious errors which offend Catholic doctrine.

[28] On the evening of Easter Sunday, 10 April 1955, during an animated discussion at the apartment of Rhoda de Terra, his personal assistant since 1949, Teilhard suffered a heart attack and died.

The unfolding of the material cosmos is described from primordial particles to the development of life, human beings and the noosphere, and finally to his vision of the Omega Point in the future, which is "pulling" all creation towards it.

[43] Even after World War II Teilhard continued to argue for racial and individual eugenics in the name of human progress, and denounced the United Nations declaration of the Equality of Races (1950) as "scientifically useless" and "practically dangerous" in a letter to the agency's director Jaime Torres Bodet.

"[44] Writing from China in October 1936, shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Teilhard expressed his stance towards the new political movement in Europe, "I am alarmed at the attraction that various kinds of Fascism exert on intelligent (?)

He felt that the choice between what he called "the American, the Italian, or the Russian type" of political economy (i.e. liberal capitalism, Fascist corporatism, Bolshevik Communism) had only "technical" relevance to his search for overarching unity and a philosophy of action.

For this reason, the most eminent and most revered Fathers of the Holy Office exhort all Ordinaries as well as the superiors of Religious institutes, rectors of seminaries and presidents of universities, effectively to protect the minds, particularly of the youth, against the dangers presented by the works of Fr.

"[59] Theodosius Dobzhansky, writing in 1973, drew upon Teilhard's insistence that evolutionary theory provides the core of how man understands his relationship to nature, calling him "one of the great thinkers of our age".

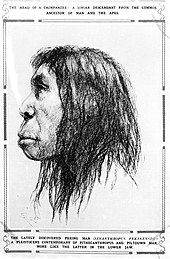

In an essay published in the magazine Natural History (and later compiled as the 16th essay in his book Hen's Teeth and Horse's Toes), American biologist Stephen Jay Gould made a case for Teilhard's guilt in the Piltdown Hoax, arguing that Teilhard has made several compromising slips of the tongue in his correspondence with paleontologist Kenneth Oakley, in addition to what Gould termed to be his "suspicious silence" about Piltdown despite having been, at that moment in time, an important milestone in his career.

In November, 1981, Oakley himself published a letter in New Scientist saying: "There is no proved factual evidence known to me that supports the premise that Father Teilhard de Chardin gave Charles Dawson a piece of fossil elephant molar tooth as a souvenir of his time spent in North Africa.

The shock value of the suggestion that the philosopher-hero was also a criminal was stunning.” Two years later, Lukas published a more detailed article in the British scholarly journal Antiquity in which she further refuted Gould, including an extensive timeline of events.

[74] William G. Pollard, the physicist and founder of the prestigious Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies (and its director until 1974), praised Teilhard’s work as "A fascinating and powerful presentation of the amazing fact of the emergence of man in the unfolding drama of the cosmos.

[81] At the same time, he supports the idea of the presence of embryos of consciousness from the very genesis of the universe: "We are logically forced to assume the existence [...] of some sort of psyche" infinitely diffuse in the smallest particle.

[93] Lucien Cuénot, the biologist who proved that Mendelism applied to animals as well as plants through his experiments with mice, wrote: "Teilhard's greatness lay in this, that in a world ravaged by neurosis he provided an answer to out modern anguish and reconciled man with the cosmos and with himself by offering him an "ideal of humanity that, through a higher and consciously willed synthesis, would restore the instinctive equilibrium enjoyed in ages of primitive simplicity.

[109][110] In 1972, the Uruguayan priest Juan Luis Segundo, in his five-volume series A Theology for Artisans of a New Humanity, wrote that Teilhard "noticed the profound analogies existing between the conceptual elements used by the natural sciences—all of them being based on the hypothesis of a general evolution of the universe.

"[111] Marguerite Teillard-Chambon [fr], (alias Claude Aragonnès) was a French writer who edited and had published three volumes of correspondence with her cousin, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, "La genèse d'une pensée" ("The Making of a Mind") being the last, after her own death in 1959.

They had shared a childhood in Auvergne; she it was who encouraged him to undertake a doctorate in science at the Sorbonne; she eased his entry into the Catholic Institute, through her connection to Emmanuel de Margerie and she introduced him to the intellectual life of Paris.