Catholic Church and Nazi Germany

[2] Mary Fulbrook wrote that when politics encroached on the church, Catholics were prepared to resist; the record was patchy and uneven, though, and (with notable exceptions) "it seems that, for many Germans, adherence to the Christian faith proved compatible with at least passive acquiescence in, if not active support for, the Nazi dictatorship".

[23] Voting preferences in the Weimar Republic were mainly determined by social class and religion, and the Catholics formed a distinguishable and tight-knit subculture within Germany, being alienated from the mainstream Protestant society as a result of the Kulturkampf and the NSDAP's strongly anti-Catholic identity.

Pius XI issued his Mit brennender Sorge encyclical, condemning racism and accusing the Nazis of violations of its treaty and "fundamental hostility" to the church;[28] Germany renewed its crackdown on and propaganda campaign against Catholics.

[41] Resistance by Bishops Johannes de Jong and Jules-Géraud Saliège, papal diplomat Angelo Rotta, and the nun Margit Slachta contrasts with the apathy and collaborationism of Slovakia's Jozef Tiso and clergy Croat nationalists.

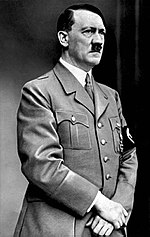

[64] Although Article 24 of the NSDAP party platform called for conditional toleration of Christian denominations and the Reichskonkordat with the Vatican was signed in 1933 (purportedly guaranteeing religious freedom for Catholics), Hitler considered religion fundamentally incompatible with Nazism.

This task does not consist solely in overcoming an ideological opponent but must be accompanied at every step by a positive impetus: in this case, that means the reconstruction of the German heritage in the widest and most comprehensive sense.Himmler saw the main task of his Schutzstaffel (SS) organisation as "acting as the vanguard in overcoming Christianity and restoring a 'Germanic' way of living" to prepare for the coming conflict between "humans and subhumans";[76] although the Nazi movement opposed Jews and Communists, "by linking de-Christianisation with re-Germanization, Himmler had provided the SS with a goal and purpose all of its own"[76] and made it a "cult of the Teutons".

Imprisoned after the 1923 Munich Beer Hall Putsch, he used the time to produce Mein Kampf; he claimed that an effeminate Jewish-Christian ethic was enfeebling Europe, and Germany needed a man of iron to restore itself and build an empire.

Dominican Province of Teutonia provincial and German resistance spiritual leader Laurentius Siemer was influential in the Committee for Matters Relating to the Orders, which formed in response to Nazi attacks on Catholic monasteries to encourage the bishops to oppose the regime more effectively.

[160] Fritz Gerlich, editor of Munich's Catholic weekly Der Gerade Weg, was killed for his criticism of the Nazis;[161] writer and theologian Dietrich von Hildebrand was forced to flee Germany.

Bishop Clemens von Galen of Münster refused, saying that interference in the curriculum violated the Reichskonkordat and children would be confused about their "obligation to act with charity to all men" and the historical mission of the people of Israel.

Faulhaber, Galen, and Pius XI continued to oppose Communism as anxiety reached a high point with what the Vatican called a "red triangle" formed by the USSR, Republican Spain and revolutionary Mexico.

The government refused to halt the program in writing, and the Vatican declared on 2 December that the policy was contrary to natural and divine law: "The direct killing of an innocent person because of mental or physical defects is not allowed".

[219] Although some clergy refused to feign support for Hitler's government, the Catholic hierarchy adopted a strategy of "seeming acceptance of the Third Reich" by couching their criticisms as motivated by a desire to "point out mistakes that some of its overzealous followers committed".

Frings wrote a pastoral letter instructing his diocese not to violate the inherent rights of others "not of our blood", even during war, and preached that "no one may take the property or life of an innocent person just because he is a member of a foreign race".

[240] Among other Catholic clerics sent to Dachau were Father Jean Bernard of Luxembourg; the Dutch Carmelite Titus Brandsma (d. 1942), Stefan Wincenty Frelichowski (d. 1945), Hilary Paweł Januszewski (d. 1945), Lawrence Wnuk, Ignacy Jeż and Adam Kozłowiecki of Poland, and Josef Lenzel and August Froehlich of Germany.

[41] During the winter of 1939–40, with Poland overrun and France and Low Countries yet to be attacked, early German military resistance sought papal assistance in preparations for a coup; Colonel Hans Oster of the Abwehr sent attorney Josef Müller on a clandestine trip to Rome.

Beginning in 1942, Sommer started to receive detailed information about the situation in Jewish ghettos, which she described as "30 to 80 people inhabiting one room; no heating; no plumbing, and four small slices of bread for a day's rations".

[273] Despite Sommer constantly pressuring the German clergy towards acting, what really lacked was intervention from the Vatican itself; historian Michael Phayer concludes that "the bishops would have risked a breach with their government had either the Pope or his nuncio in Berlin, Cesare Orsenigo, pushed or led them in this direction.

Wirmer was a leftist member of the Centre Party, had worked to forge ties between the civilian resistance and the trade unions, and was a confidant of Jakob Kaiser (a leader of the Christian trade-union movement, which Hitler banned after taking office).

[287] According to Mary Fulbrook, Catholics were prepared to resist when politics encroached on the church; otherwise, their record was uneven: "It seems that, for many Germans, adherence to the Christian faith proved compatible with at least passive acquiescence in, if not active support for, the Nazi dictatorship".

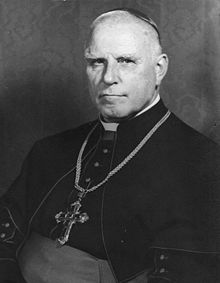

"[79] Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber drafted the Holy See's response to the Nazi-Fascist axis in January 1937; Pius issued Mit brennender Sorge in March, noting the "threatening storm clouds" of a religious war over Germany.

"[304] Heinrich Himmler's SS newspaper, Das Schwarze Korps (The Black Corps), had called Pacelli a "co-conspirator with Jews and Communists against Nazism" and decried his election as "the "Chief Rabbi of the Christians, boss of the firm of Judah-Rome.

[337] Pius protested the deportation of Slovakian Jews to the Bratislava government in 1942; the following year, he wrote: "The Holy See would fail in its Divine Mandate if it did not deplore these measures, which gravely damage man in his natural right, mainly for the reason that these people belong to a certain race.

[b] In December 1942, when Secretary of State Maglione was asked if Pius would issue a proclamation similar to the Allied "German Policy of Extermination of the Jewish Race", he replied that the Vatican was "unable to denounce publicly particular atrocities".

[341] Although the assessment of Pius's role during World War II was positive shortly after his death, historical documents have revealed his early knowledge of the Shoah and his refusal to perform vital actions in order to save Jews when the opportunities to do so presented themselves.

[343][344] During the summer of 1942, Pius explained to the College of Cardinals the theological gulf between Jews and Christians: "Jerusalem has responded to His call and to His grace with the same rigid blindness and stubborn ingratitude that has led it along the path of guilt to the murder of God."

[346] A number of historians have refuted Cornwell's conclusions;[347][348][349][350][351] he later moderated his accusations,[348][349][352] saying that it was "impossible to judge [Pius'] motives"[350][351] but "nevertheless, due to his ineffectual and diplomatic language in respect of the Nazis and the Jews, I still believe that it was incumbent on him to explain his failure to speak out after the war.

Evidence suggests that Pius XII tacitly approved his work; according to reports from Counterintelligence Corps agent Robert Mudd, about 100 Ustaše were in hiding at the Pontifical Croatian College of St. Jerome in the hope of reaching Argentina (with Vatican knowledge).

In 1948, he brought Nazi collaborator and wanted war criminal Ante Pavelić to the Pontifical Latin American College disguised as a priest until Argentine President Juan Perón invited him to his country.

Catholic clergy smuggled Jews from Germany and German-occupied Austria through "monastery routes"(*Klosterroute*), where they either lived in Italian refugee camps in relative safety or were given falsified papers and emigrated to South America.