Pietism

Pietism originated in modern Germany in the late 17th century with the work of Philipp Spener, a Lutheran theologian whose emphasis on personal transformation through spiritual rebirth and renewal, individual devotion, and piety laid the foundations for the movement.

Pietism spread from Germany to Switzerland, the rest of German-speaking Europe, and to Scandinavia and the Baltics, where it was heavily influential, leaving a permanent mark on the region's dominant Lutheranism, with figures like Hans Nielsen Hauge in Norway, Peter Spaak and Carl Olof Rosenius in Sweden, Katarina Asplund in Finland, and Barbara von Krüdener in the Baltics, and to the rest of Europe.

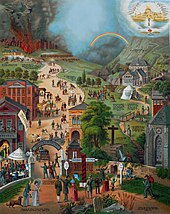

There, it influenced Protestants of other ethnic and other (non-Lutheran) denominational backgrounds, contributing to the 18th-century foundation of evangelicalism, an interdenominational movement within Protestantism that today has some 300 million followers.

[16] Pietistic Lutheranism entered Sweden in the 1600s after the writings of Johann Arndt, Philipp Jakob Spener, and August Hermann Francke became popular.

[3] As the forerunners of the Pietists in the strict sense, certain voices had been heard bewailing the shortcomings of the church and advocating a revival of practical and devout Christianity.

Born at Rappoltsweiler in Alsace, now in France, on 13 January 1635, trained by a devout godmother who used books of devotion like Arndt's True Christianity, Spener was convinced of the necessity of a moral and religious reformation within German Lutheranism.

He afterwards spent a year in Geneva, and was powerfully influenced by the strict moral life and rigid ecclesiastical discipline prevalent there, and also by the preaching and the piety of the Waldensian professor Antoine Leger and the converted Jesuit preacher Jean de Labadie.

In 1675, Spener published his Pia desideria or Earnest Desire for a Reform of the True Evangelical Church, the title giving rise to the term "Pietists".

In Pia desideria, Spener made six proposals as the best means of restoring the life of the church: This work produced a great impression throughout Germany.

Three magistrates belonging to that society, one of whom was August Hermann Francke, subsequently the founder of the famous orphanage at Halle (1695), commenced courses of expository lectures on the Scriptures of a practical and devotional character, and in the German language, which were zealously frequented by both students and townsmen.

The lectures aroused the ill-will of the other theologians and pastors of Leipzig, and Francke and his friends left the city, and with the aid of Christian Thomasius and Spener founded the new University of Halle.

Authorities within state-endorsed Churches were suspicious of pietist doctrine which they often viewed as a social danger, as it "seemed either to generate an excess of evangelical fervor and so disturb the public tranquility or to promote a mysticism so nebulous as to obscure the imperatives of morality.

[20] As a distinct movement, Pietism had its greatest strength by the middle of the 18th century; its very individualism in fact helped to prepare the way for the Enlightenment (Aufklärung), which took the church in an altogether different direction.

Yet some claim that Pietism contributed largely to the revival of Biblical studies in Germany and to making religion once more an affair of the heart and of life and not merely of the intellect.

[4] As such, Laestadius "spend the rest of his life advancing his idea of Lutheran pietism, focusing his energies on marginalized groups in the northernmost regions of the Nordic countries".

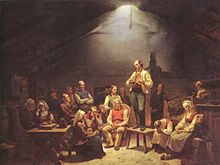

[22] Laestadian Lutherans gather in a central location for weeks at a time for summer revival services in which many young adults find their future spouses.

[6] Radical Pietism are those Christian Churches who decided to break with denominational Lutheranism in order to emphasize certain teachings regarding holy living.

John Wesley was influenced significantly by Moravians (e.g., Zinzendorf, Peter Boehler) and Pietists connected to Francke and Halle Pietism.

Balmer says that: Evangelicalism itself, I believe, is a quintessentially North American phenomenon, deriving as it did from the confluence of Pietism, Presbyterianism, and the vestiges of Puritanism.

[32] In the United States, Richard L. McCormick says, "In the nineteenth century voters whose religious heritage was pietistic or evangelical were prone to support the Whigs and, later, the Republicans."

"[33] McCormick notes that the key link between religious values and politics resulted from the "urge of evangelicals and Pietists to 'reach out and purge the world of sin'".

[35] In England in the late 19th and early 20th century, the Nonconformist Protestant denominations, such as the Methodists, Baptists and Congregationalists, formed the base of the Liberal Party.