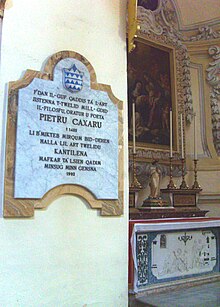

Pietru Caxaro

The Dominicans had originally arrived in Malta around 1450, and quickly forged good friendships amongst the literary population and professional people, including academics.

However, her brother, a Canon at the bishop's cathedral chapter, objected on the grounds of “spiritual affinity”, since Caxaro's father was a godfather to Franca.

[citation needed] Despite the fact that Caxaro did all he could to win Franca over, and also obtained the official blessing of the bishop of Malta, the marriage did not take place.

Peter Caxaro was virtually unknown[2] until he was made famous in 1968 by the publication of his Cantilena by the Dominican Mikiel Fsadni and Godfrey Wettinger.

[11] Both friars based their information on a common source; namely, on the Descrittione delli Tre Conventi che l’Ordine dei Predicatori tiene nell’Isola di Malta, I, 1, by Francesco Maria Azzopardo O.P., written about 1676.

[15] The composition proves that Caxaro's qualification as a philosopher, poet and orator is fully justified since its construction is professionally accomplished.

[25] It must be noticed, however, that Giovanni Francesco Abela, in his Descrittione of 1647,[26] did not include Caxaro in his list of some forty-six Houmini di Malta per varie guise d’eccellenza celebri, e famosi,[27] of which not all are that illustrious.

The known sources of Caxaro's biographical data are few, namely four,[28] the State Archives of Palermo, Sicily (Protocollo del Regno, mainly vol.

The first known date regarding Caxaro is April 1, 1438, when he set for the examination to be given the warrant of public notary of Malta and Gozo by the competent authorities in Palermo, Sicily.

In support of his claim he proposed that Caxaro's Cantilena was in fact a zajal, which in Arabic refers to a song which the Jews of Spain (and Sicily) adopted and promoted.

Wettinger and Fsadni had suggested[52] that it was the consolation which Brandan saw in the content of the composition that prompted him to leave us a memory of it, writing it down in one of the registers of his acts.

[62] In the rest of the Cantilena’s prologue, which is formally in accord with the general practice of the times,[63] the poetic rather than the philosophical or oratorical excellences of Caxaro are emphasized.

He later established himself as a translator, compiler and commentator of classical texts, therefore giving rise to a literary culture concerned with human interests.

[citation needed] Caxaro's father, in the course of his constant voyaging between Catalonia, Sicily and Malta, like so many other tradesmen of his time, came in contact with the then prevailing environment of Spain's Mediterranean city-harbours.

From the first half of the 15th century onwards, Palermo went through an enormous and impressive economic, demographic and urbanistic development,[69] manifesting a substantial cultural facelift.

Though the times were rather difficult due to the frequent incursions of the Turks, and the disastrous effect of epidemics and other diseases,[70] the enthusiasts of the humanæ litteræ were great in number.

[74] In those days, the large number of intellectuals and law students considered the juridical culture as instrumental in acquiring a worthy social standing.

Moreover, while the use of the vulgar tongues became established as a practised norm,[76] the so-called cultura del decoro of the humanists became, more than restricted to cultural circles, a quality of life.

Caxaro's sojourn at Palermo in 1438 must have recalled to him King Alphonse's stop in Malta, amidst great pomp and exultation, five years earlier.

All of these extensively admired classical antiquity, idealising its splendour and richness, and dreaming of an ideal society equivalent to that apparently gorgeous achievement.

[85] Being the cultural climax of all that has been done in the Middle Ages, the humanist wave of erudition superbly retrieved the Latin, Greek and Christian classical literature, with its proper techniques, methods, forms and tastes.

It also gave rise to the printing press, the libraries, to new universities, paternities and literary associations, such as the renowned Academic Platonica of Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499).

In other words, a true renaissance with its proper philosophy which recognises the value and dignity of man and makes him, as Protagoras would have it, the “measure of all things”, somehow taking human nature, its limits and delimits, together with its interests, as it main theme.

[91] However, much work has to be done in this field, especially by scholars with professional standing on mediaeval Arabic, Spanish and Sicilian idioms, dialects and poetic forms.

Due to the Cantilena’s uniqueness interesting results have been put forward by historical linguistics,[92] emphasising the drastic changes in the Maltese language over a span of four centuries.

It must be admitted that a foreigner, even if expert in this field of study, but unfamiliar to a Maltese way of thinking, will find the text difficult and obscure.

In March of that same year,[106] the Augustinian Matteo di Malta had been commissioned as the town-council's ambassador to lead the talks with the viceroy on the question so as to provide funds for their urgent restoration.

So as to take immediate action and prevent further immanent collapse of the walls, at the town-council sitting of January 11[108] Peter Caxaro, acting as secretary, spoke in favour of an urgent collecta (which was later effected), with the approval of the whole house.

[111] The general melancholic tone of the composition did not pass unnoticed,[112] though it had been recognised that the final note sounded the victory of hope over desperation; the building anew over the ruins of unfulfilled dreams or ambitions.

[118] Others have indeed valued its content highly,[119] wisely noting that the subject is entirely profane (as opposed to the sacred), and moreover sheds light on the concrete versus abstract thinking of the populace (a feature common amongst Mediterranean peoples unto this day); reality against illusion.