Pike (weapon)

[citation needed] It was approximately 2 to 6 kg (4.4 to 13.2 lb) in weight, with the 16th-century military writer Sir John Smythe recommending lighter rather than heavier pikes.

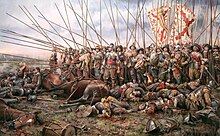

When the troops of opposing armies both carried the pike, it often grew in a sort of arms race, getting longer in both shaft and head length to give one side's pikemen an edge in combat.

The men were all moving forward facing in a single direction and could not turn quickly or efficiently to protect the vulnerable flanks or rear of the formation.

[citation needed] As a result, such mobile pike formations sought to have supporting troops protect their flanks or would maneuver to smash the enemy before they could be outflanked themselves.

[4] Although very long spears had been used since the dawn of organized warfare (notably illustrated in art showing Sumerian and Minoan warriors and hunters), the earliest recorded use of a pike-like weapon in the tactical method described above involved the Macedonian sarissa, used by the troops of Alexander the Great's father, Philip II of Macedon, and successive dynasties, which dominated warfare for several centuries in many countries.

These formations were essentially immune to the attacks of mounted men-at-arms as long as the knights obligingly threw themselves on the spear wall and the foot soldiers remained steady under the morale challenge of facing a cavalry charge, but the closely packed nature of pike formations rendered them vulnerable to enemy archers and crossbowmen who could shoot them down with impunity, especially when the pikemen did not have adequate armor.

At the Battle of Laupen (1339), Bernese pikemen overwhelmed the infantry forces of the opposing Habsburg/Burgundian army with a massive charge before wheeling over to strike and rout the Austro-Burgundian horsemen as well.

At the same time however such aggressive action required considerable tactical cohesiveness or suitable terrain to protect the vulnerable flanks of the pike formations especially from the attack of mounted man-at-arms.

[citation needed] The constant success of the Swiss mercenaries in the later period was attributed to their extreme discipline and tactical unity due to semi-professional nature, allowing a pike block to somewhat alleviate the threat presented by flanking attacks.

In 1391, a decree by Gian Galeazzo Visconti ordered the pikes to be at least 10 feet long in Milan, equivalent to 4.35 m (14.3 ft) and their tips to be reinforced with iron strips to prevent enemies, given their length, from cutting or breaking them.

The Scots predominantly used shorter spears in their schiltron formation; their attempt to adopt the longer Continental pike was dropped for general use after its ineffective use led to humiliating defeat at the Battle of Flodden.

Such Swiss and Landsknecht phalanxes also contained men armed with two-handed swords, or Zweihänder, and halberdiers for close combat against both infantry and attacking cavalry.

The deep pike attack column remained the primary form of effective infantry combat for the next forty years, and the Swabian War saw the first conflict in which both sides had large formations of well-trained pikemen.

Apart from being used by soldiers in battle, a tassel fixed to the socket of the head together with optional further embellishment made the Schefflin an appropriate main weapon for princely bodyguards and courtly officials.

[citation needed] The quintessential example of this development was the Spanish tercio, which consisted of a large square of pikemen with small, mobile squadrons of arquebusiers moving along its perimeter, as well as traditional men-at-arms.

The Tercio deployed smaller numbers of pikemen than the huge Swiss and Landsknecht columns, and their formation ultimately proved to be much more flexible on the battlefield.

Furthermore, improvements in artillery caused most European armies to abandon large formations in favor of multiple staggered lines, both to minimize casualties and to present a larger frontage for volley fire.

Thick hedges of bayonets proved to be an effective anti-cavalry solution, and improved musket firepower was now so deadly that combat was often decided by shooting alone.

[14] During the American Revolution (1775–1783), pikes called "trench spears" made by local blacksmiths saw limited use until enough bayonets could be procured for general use by both Continental Army and attached militia units.

Throughout the Napoleonic era, the spontoon, a type of shortened pike that typically had a pair of blades or lugs mounted to the head, was retained as a symbol by some NCOs; in practice it was probably more useful for gesturing and signaling than as a weapon for combat.

As late as Poland's Kościuszko Uprising in 1794, the pike reappeared as a child of necessity which became, for a short period, a surprisingly effective weapon on the battlefield.

The peasant "pikemen" armed with these crude instruments played a pivotal role in securing a near impossible victory against a far larger and better equipped Russian army at the Battle of Racławice, which took place on 4 April 1794.

As late as the Napoleonic Wars, at the beginning of the 19th century, even the Russian militia (mostly landless peasants, like the Polish partisans before them) could be found carrying shortened pikes into battle.

As the 19th century progressed, the obsolete pike would still find a use in such countries as Ireland, Russia, China, and Australia, generally in the hands of desperate peasant rebels who did not have access to firearms.

One attempt to resurrect the pike as a primary infantry weapon occurred during the American Civil War (1861–1865) when the Confederate States of America planned to recruit twenty regiments of pikemen in 1862.

The great Hawaiian warrior king Kamehameha I had an elite force of men armed with very long spears who seem to have fought in a manner identical to European pikemen, despite the usual conception of his people's general disposition for individualistic dueling as their method of close combat.

However, these hand-held weapons never left the stores after the pikes had "generated an almost universal feeling of anger and disgust from the ranks of the Home Guard, demoralised the men and led to questions being asked in both Houses of Parliament".