Tercio

The Spanish tercios were one of the finest professional infantries in the world due to the effectiveness of their battlefield formations and were a crucial step in the formation of modern European armies, made up of professional volunteers, instead of levies raised for a campaign or hired mercenaries typically used by other European countries of the time.

The internal administrative organization of the tercios and their battlefield formations and tactics, grew out of the innovations of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba during the conquest of Granada and the Italian Wars in the 1490s and 1500s, being among the first to effectively mix pikes and firearms (arquebuses).

Following their formal establishment in 1534, the reputation of the tercio was built upon their effective training and high proportion of "old soldiers" (veteranos), in conjunction with the particular elan imparted by the lower nobility who commanded them.

During the Granada War (1482–1491), the soldiers of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain were divided into three classes: pikemen (modelled after the Swiss), swordsmen with shields, and crossbowmen supplemented with an early firearm the arquebus.

[citation needed] As shields disappeared and firearms replaced crossbows, Spain won victory after victory in Italy against powerful French armies, beginning under the leadership of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba (1453–1515), nicknamed El Gran Capitán (The Great Captain)[4] The military organizational and tactical changes made by Córdoba to the armies of Spanish monarchs are seen as the precursors of the tercios and their methods of warfare.

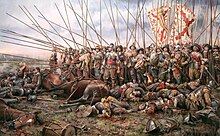

An advantage of the Spanish pike and shot formation over the Swiss compact frame that had inspired it was in its ability to divide into mobile units and even individual melee without the loss of cohesion.

[citation needed] By the middle of the 17th century, the tercios began to be raised by nobles at their own expense, patrons who appointed the captains and were effective owners of the units, as in other contemporaneous European armies.

From the conquest of Granada in 1492 to the campaigns of El Gran Capitán in the kingdom of Naples in 1495, three ordinances laid the foundations of Spanish military administration.

[citation needed] In 1557, the Spanish army completely defeated the French at the Battle of San Quentin, and again in 1558 at Gravelines, which led to a peace greatly favoring Spain.

The one tercio with spears, as the Germans brought them, which they called pikes; and the other had the name of shields [people of swords]; and the other, of crossbowmen and spit bearers.

This last explanation is supported by the field master Sancho de Londoño in a report to the Duke of Alba in the 16th century: The tercios, although they were instituted in imitation of the [Roman] legions, in few things can be compared to them, that the number is half, and although formerly there were three thousand soldiers, for which they were called tercios and not legions, already it is said like this even if they do not have more than a thousand men.

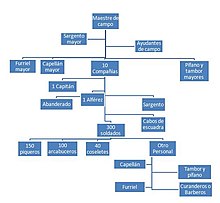

[12] Initially, each tercio that served in Italy and the Spanish Netherlands was organized into: The companies were later reduced to 250 men and the ratio of arquebusiers (later musketmen) to pikemen steadily increased.

Similar to military organization today, a tercio was led by a maestre de campo (commanding officer) appointed by the king, with a guard of eight halberdiers.

A sergeant served as second-in-command of a company and transmitted the captain's orders; furrieles provided weapons and munitions, as well as additional manpower; corporals led groups of 25 (similar to today's platoons), watching for disorder in the unit.

However, as the formation matured in practice, the number of swordsmen was reduced and then eliminated and the ratio of gunmen to pikemen increased over time.

Sometimes later tercios did not stick to the all-volunteer model of the regular Imperial Spanish army – when the Habsburg king Philip II found himself in need of more troops, he raised a tercio of Catalan criminals to fight in Flanders,[13] a trend he continued with mostly Catalan criminals for the rest of his reign.

The victor of Nieuwpoort, the Dutch stadtholder Maurice, Prince of Orange, believed he could improve on the tercio by combining its methods with the organisation of the Roman legion.

The Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) in the Low Countries continued to be characterized by sieges of cities and forts, while field battles were of secondary importance.

Maurice's reforms did not lead to a revolution in warfare, but he had created an army that could meet the tercios' battle formations on an even basis and that pointed the way to future developments.

However, the tried-and-true tactics and professionalism of the Spanish tercios played a decisive role in defeating the Swedish army at the Battle of Nördlingen.

The classic pike and shot square formations fielded by the Spanish tercios and good cavalry support continued to win major battles in the 17th century, such as Wimpfen (1622), Fleurus (1622), Breda (1624), Nördlingen (1634), Thionville (1639), and Honnecourt (1641).

[18] This Royal Military and Mathematics Academy in Flanders was renowned for the diverse origin of its officer cadets, for the innovative features of its plan of studies produced by Sebastián Fernández de Medrano, the theoretical and practical basis of its learning process apart from the relevant assignments given to its officer cadets who were also known as the “Great Masters of War” coined by the treatise writer, Count of Clonard.