Body hair

From childhood onward, regardless of sex, vellus hair covers almost the entire area of the human body.

Exceptions include the lips, the backs of the ears, palms of hands, soles of the feet, certain external genital areas, the navel, and scar tissue.

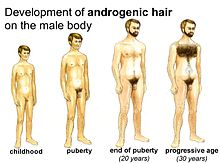

During the final stages of puberty and extending into adulthood, men grow increasing amounts of terminal hair over the chest and abdomen areas.

Terminal hair growth on arms is a secondary sexual characteristic in boys and appears in the last stages of puberty.

This type of intense arm vellus hair growth sometimes occurs in girls and children of both sexes until puberty.

[2] Visible hair appearing on the top surfaces of the feet and toes generally begins with the onset of puberty.

For a variety of reasons, people may shave their leg hair, including cultural practice or individual needs.

However, athletes of both sexes – swimmers, runners, cyclists and bodybuilders in particular – may shave their androgenic hair to reduce friction, highlight muscular development or to make it easier to get into and out of skin-tight clothing.

Zoologist Desmond Morris disputes theories that it developed to signal sexual maturity or protect the skin from chafing during copulation, and prefers the explanation that pubic hair acts as a scent trap.

At this time, the pituitary gland secretes gonadotropin hormones which trigger the production of testosterone in the testicles and ovaries, promoting pubic hair growth.

Underarm hair normally starts to appear at the beginning of puberty, with growth usually completed by the end of the teenage years.

While underarm shaving was quickly adopted in some English speaking countries, especially in the US and Canada, it did not become widespread in Europe until well after World War II.

It is common for many women to develop a few facial hairs under or around the chin, along the sides of the face (in the area of sideburns), or on the upper lip.

In some cases, female beard growth is the result of a hormonal imbalance (usually androgen excess), or a rare genetic disorder known as hypertrichosis.

When goose bumps are observed, small muscles (arrector pili muscle) contract to raise the hairs either to provide insulation, by reducing cooling of the skin by air convection, or in response to central nervous stimulus, similar to the feeling of "hairs standing up on the back of your neck".

Keratin however can easily be damaged by excessive heat and dryness, suggesting that extreme sun exposure, perhaps due to a lack of clothing, would result in perpetual hair destruction, eventually resulting in the genes being bred out in favor of high skin pigmentation.

[11] Markus J. Rantala of the Department of Biological and Environmental Science, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, said humans evolved by "natural selection" to be hairless when the trade off of "having fewer parasites" became more important than having a "warming, furry coat".

[13] Loss of fur occurred at least two million years ago, but possibly as early as 3.3 million years ago judging from the divergence of head and pubic lice, and aided persistence hunting (the ability to catch prey in very long distance chases) in the warm savannas where hominins first evolved.

The two main advantages are felt to be bipedal locomotion and greater thermal load dissipation capacity due to better sweating and less hair.

[15] Anthropologist Joseph Deniker said in 1901 that the very hirsute peoples are the Ainus, Uyghurs, Iranians, Australian aborigines (Arnhem Land being less hairy), Toda, Dravidians and Melanesians, while the most glabrous peoples are the Indigenous Americans, San, and East Asians, who include Chinese, Koreans, Mongols, and Malays.

[16] Deniker said that hirsute peoples tend to have thicker beards, eyelashes, and eyebrows but fewer hairs on their scalp.

They summarize other studies on prevalence of this trait as reporting, in general, that Caucasoids are more likely to have hair on the middle finger joint than Negroids, Australoids and Mongoloids, and collect the following frequencies from previously published literature: Andamanese 0%, Inuit 1%, African American 16% or 28%, Ethiopians 25.6%, Mexicans of the Yucatan 20.9%, Penobscot and Shinnecock 22.7%, Gurkha 33.6%, Japanese 44.6%, various Hindus 40–50%, Egyptians 52.3%, Near Eastern peoples 62–71%, various Europeans 60–80%.

[24] Milkica Nešić and her colleagues from the Department of Physiology at the University of Niš, Serbia, cited prior studies in a 2010 publication indicating that the frequency of hair on the middle finger joint (mid-phalangeal hair) in Europeans is significantly higher than in African populations, where the lowest values were found, and "completely absent" in Northern Native American (Inuit) populations.

For example, even when one's particular distinguishing features such as face and tattoos are obscured, persons can still be identified by their hair on other parts of their body.