Infrared sensing in snakes

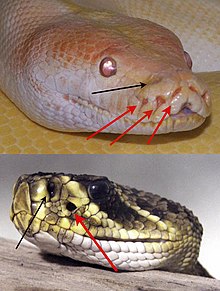

The ability to sense infrared thermal radiation evolved independently in three different groups of snakes, consisting of the families of Boidae (boas), Pythonidae (pythons), and the subfamily Crotalinae (pit vipers).

The more advanced infrared sense of pit vipers allows these animals to strike prey accurately even in the absence of light, and detect warm objects from several meters away.

In crotalines, information from the pit organ is relayed to the nucleus reticularus caloris in the medulla via the lateral descending trigeminal tract.

In boas and pythons, information from the labial pit is sent directly to the contralateral optic tectum via the lateral descending trigeminal tract, bypassing the nucleus reticularus caloris.

This portion of the brain receives other sensory information as well, most notably optic stimulation, but also motor, proprioceptive and auditory.

However, studies that have visualized the thermal images seen by the facial pit using computer analysis have suggested that the resolution is extremely poor.

It senses infrared signals through a mechanism involving warming of the pit organ, rather than chemical reaction to light.

This is consistent with the very thin pit membrane, which would allow incoming infrared radiation to quickly and precisely warm a given ion channel and trigger a nerve impulse, as well as the vascularization of the pit membrane in order to rapidly cool the ion channel back to its original temperature state.

While the molecular precursors of this mechanism are found in other snakes, the protein is both expressed to a much lower degree and much less sensitive to heat.

[12] Infrared sensing snakes use pit organs extensively to detect and target warm-blooded prey such as rodents and birds.