Positional notation

Initially inferred only from context, later, by about 700 BC, zero came to be indicated by a "space" or a "punctuation symbol" (such as two slanted wedges) between numerals.

287–212 BC) invented a decimal positional system based on 108 in his Sand Reckoner;[2] 19th century German mathematician Carl Gauss lamented how science might have progressed had Archimedes only made the leap to something akin to the modern decimal system.

[3] Hellenistic and Roman astronomers used a base-60 system based on the Babylonian model (see Greek numerals § Zero).

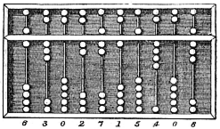

With counting rods or abacus to perform arithmetic operations, the writing of the starting, intermediate and final values of a calculation could easily be done with a simple additive system in each position or column.

This approach required no memorization of tables (as does positional notation) and could produce practical results quickly.

Decimal fractions were first developed and used by the Chinese in the form of rod calculus in the 1st century BC, and then spread to the rest of the world.

[6][7] J. Lennart Berggren notes that positional decimal fractions were first used in the Arab by mathematician Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi as early as the 10th century.

[8] The Jewish mathematician Immanuel Bonfils used decimal fractions around 1350, but did not develop any notation to represent them.

[9] The Persian mathematician Jamshīd al-Kāshī made the same discovery of decimal fractions in the 15th century.

[10][11] The adoption of the decimal representation of numbers less than one, a fraction, is often credited to Simon Stevin through his textbook De Thiende;[12] but both Stevin and E. J. Dijksterhuis indicate that Regiomontanus contributed to the European adoption of general decimals:[13] In the estimation of Dijksterhuis, "after the publication of De Thiende only a small advance was required to establish the complete system of decimal positional fractions, and this step was taken promptly by a number of writers ... next to Stevin the most important figure in this development was Regiomontanus."

Dijksterhuis noted that [Stevin] "gives full credit to Regiomontanus for his prior contribution, saying that the trigonometric tables of the German astronomer actually contain the whole theory of 'numbers of the tenth progress'.

When describing base in mathematical notation, the letter b is generally used as a symbol for this concept, so, for a binary system, b equals 2.

Another common way of expressing the base is writing it as a decimal subscript after the number that is being represented (this notation is used in this article).

But if the number-base is increased to 11, say, by adding the digit "A", then the same three positions, maximized to "AAA", can represent a number as great as 1330.

Hex is 0–9 A–F, where the ten numerics retain their usual meaning, and the alphabetics correspond to values 10–15, for a total of sixteen digits.

Converting each digit is a simple lookup table, removing the need for expensive division or modulus operations; and multiplication by x becomes right-shifting.

However, other polynomial evaluation algorithms would work as well, like repeated squaring for single or sparse digits.

[citation needed] This contrasts with the numbers used by Hellenistic and Renaissance astronomers, who used thirds, fourths, etc.

In the 1930s, Otto Neugebauer introduced a modern notational system for Babylonian and Hellenistic numbers that substitutes modern decimal notation from 0 to 59 in each position, while using a semicolon (;) to separate the integral and fractional portions of the number and using a comma (,) to separate the positions within each portion.

Hexadecimal, decimal, octal, and a wide variety of other bases have been used for binary-to-text encoding, implementations of arbitrary-precision arithmetic, and other applications.

Base-12 systems (duodecimal or dozenal) have been popular because multiplication and division are easier than in base-10, with addition and subtraction being just as easy.

The Welsh language continues to use a base-20 counting system, particularly for the age of people, dates and in common phrases.

It was cursive by rounding off rational numbers smaller than 1 to 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64, with a 1/64 term thrown away (the system was called the Eye of Horus).

A number of Australian Aboriginal languages employ binary or binary-like counting systems.

For example, in Kala Lagaw Ya, the numbers one through six are urapon, ukasar, ukasar-urapon, ukasar-ukasar, ukasar-ukasar-urapon, ukasar-ukasar-ukasar.

A base-8 system (octal) was devised by the Yuki tribe of Northern California, who used the spaces between the fingers to count, corresponding to the digits one through eight.

[23] Many ancient counting systems use five as a primary base, almost surely coming from the number of fingers on a person's hand.

The Telefol language, spoken in Papua New Guinea, is notable for possessing a base-27 numeral system.

Interesting properties exist when the base is not fixed or positive and when the digit symbol sets denote negative values.

This system can be used to solve the balance problem, which requires finding a minimal set of known counter-weights to determine an unknown weight.

Lower row horizontal form