Suanpan

The word "abacus" was first mentioned by Xu Yue (160–220) in his book suanshu jiyi (算数记遗), or Notes on Traditions of Arithmetic Methods, in the Han dynasty.

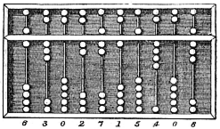

As it described, the original abacus had five beads (suan zhu) bunched by a stick in each column, separated by a transverse rod, and arrayed in a wooden rectangle box.

The long scroll Along the River During Qing Ming Festival painted by Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145) during the Song dynasty (960–1279) might contain a suanpan beside an account book and doctor's prescriptions on the counter of an apothecary.

In the 13th century, Guo Shoujing (郭守敬) used Zhusuan to calculate the length of each orbital year and found it to be 365.2425 days.

However, no direct connection can be demonstrated, and the similarity of the abaci could be coincidental, both ultimately arising from counting with five fingers per hand.

Another possible source of the suanpan is Chinese counting rods, which operated with a place value decimal system with empty spot as zero.

[9]The most mysterious and seemingly superfluous fifth lower bead, likely inherited from counting rods as suggested by the image above, was used to simplify and speed up addition and subtraction somewhat, as well as to decrease the chances of error.

[10] Its use was demonstrated, for example, in the first book devoted entirely to suanpan: Computational Methods with the Beads in a Tray (Pánzhū Suànfǎ 盤珠算法) by Xú Xīnlǔ 徐心魯 (1573, Late Ming dynasty).

In the past, the chinese used the traditional system of measurements called the Shì yòng zhì (市用制) for its suanpan.

In Shì yòng zhì (市用制), the unit of weight the jīn (斤), was defined as 16 liǎng (兩), which made it necessary to perform calculations in hexadecimal.

When the intermediate result (in multiplication and division) is larger than 15 (fifteen), the second (extra) upper bead is moved halfway to represent ten (xuanchu, suspended).

The mnemonics/readings of the Chinese division method [Qiuchu] has its origin in the use of bamboo sticks [Chousuan], which is one of the reasons that many believe the evolution of suanpan is independent of the Roman abacus.

[14] Zhusuan is named after the Chinese name of abacus, which has been recognised as one of the Fifth Great Innovation in China[15] While deciding on the inscription, the Intergovernmental Committee noted that "Zhusuan is considered by Chinese people as a cultural symbol of their identity as well as a practical tool; transmitted from generation to generation, it is a calculating technique adapted to multiple aspects of daily life, serving multiform socio-cultural functions and offering the world an alternative knowledge system.

For example, ‘Iron Abacus’ (鐵算盤) refers to someone good at calculating; ‘Plus three equals plus five and minus two’ (三下五除二; +3 = +5 − 2) means quick and decisive; ‘3 times 7 equals 21’ indicates quick and rash; and in some places of China, there is a custom of telling children's fortune by placing various daily necessities before them on their first birthday and letting them choose one to predict their future lives.

Early electronic calculators could only handle 8 to 10 significant digits, whereas suanpans can be built to virtually limitless precision.

As digitalised calculators seemed to be more efficient and user-friendly, their functional capacities attract more technological-related and large scale industries in application.

It contributes to the advancement of calculating techniques and intellectual development, which closely relate to the cultural-related industry like architecture and folk customs.