Placebo in history

The full sentence, from the Vulgate, is Placebo Domino in regione vivorum 'I will please the Lord in the land of the living', from Psalm 116:9.

It was moving towards a paradigm in which the patient became the recipient of a more standardized form of intervention that was determined by the prevailing opinions of the medical profession of the day.

[9] The last vestiges of the "consoling" approach to treatment were the prescription of morale-boosting and pleasing remedies, such as the "sugar pill", electuary or pharmaceutical syrup; all of which had no known pharmacodynamic action, even at the time.

[citation needed] In 1811, Hooper's Quincy's Lexicon–Medicum defined placebo as "an epithet given to any medicine adapted more to please than benefit the patient".

Early implementations of placebo controls date back to 16th-century Europe with Catholic efforts to discredit exorcisms.

He suggests to solve this dilemma by appropriating the meaning response in medicine, that is make use of the placebo effect, as long as the "one administering... is honest, open, and believes in its potential healing power".

[3] In 1903, Richard Cabot said that he was brought up to use placebos,[3] but he ultimately concluded by saying that "I have not yet found any case in which a lie does not do more harm than good".

[15] The placebo effect of new drugs was known anecdotally in the 18th century, as demonstrated by Michel-Philippe Bouvart's 1780s quip to a patient that she should "take [a remedy] ... and hurry up while it [still] cures.

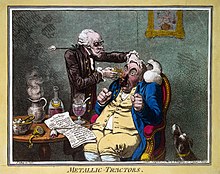

[21] He tested a popular medical treatment of his time, called "Perkins tractors", which were metal pointers supposedly able to 'draw out' disease.

[22] The wooden pointers were just as useful as the expensive metal ones, showing "to a degree which has never been suspected, what powerful influence upon diseases is produced by mere imagination".

[25] At the Royal London Hospital in 1933, William Evans and Clifford Hoyle experimented with 90 subjects and published studies which compared the outcomes from the administration of an active drug and a dummy simulator ("placebo") in the same trial.

[26] A similar experiment was carried out by Harry Gold, Nathaniel Kwit and Harold Otto in 1937, with the use of 700 subjects.

Recently Beecher’s article was reanalyzed with surprising results: In contrast to his claim, no evidence was found of any placebo effect in any of the studies cited by him.In 1961 Henry K. Beecher concluded[31] that surgeons he categorized as enthusiasts relieved their patients' chest pain and heart problems more than skeptic surgeons.

[11] In 1961 Walter Kennedy introduced the word nocebo to refer to a neutral substance that creates harmful effects in a patient who takes it.