William Osler

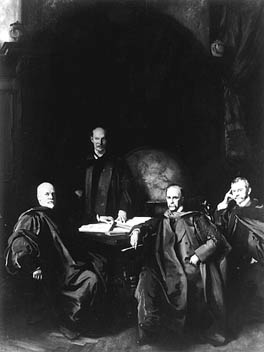

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, FRS FRCP (/ˈɒzlər/; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the "Big Four" founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital.

[5] One of William's uncles, Edward Osler (1798–1863), a medical officer in the Royal Navy, wrote the Life of Lord Exmouth and the poem The Voyage.

In 1831, Featherstone Osler was invited to serve on HMS Beagle as the science officer for Charles Darwin's historic voyage to the Galápagos Islands, but he turned it down because his father was dying.

[7] As a teenager, Featherstone Osler was aboard HMS Sappho when it was nearly destroyed by Atlantic storms and remained adrift for weeks.

When Featherstone and his bride, Ellen Free Picton, arrived in Canada, they were nearly shipwrecked again on Egg Island in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

In 1867, Osler announced that he would follow his father's footsteps into the ministry and entered Trinity College of the University of Toronto, in the autumn.

Osler lived with James Bovell for a time, and through Johnson, he was introduced to the writings of Sir Thomas Browne; his Religio Medici caused a deep impression on him.

Following post-graduate training under Rudolf Virchow in Germany, Osler returned to the McGill University Faculty of Medicine as a professor in 1874.

When he left Philadelphia in 1889, his farewell address, "Aequanimitas",[14] was about the imperturbability (calm amid storm) and equanimity (moderated emotion, tolerance) necessary for physicians.

While at Hopkins, Osler established the full-time, sleep-in residency system whereby staff physicians lived in the administration building of the hospital.

[2] The contribution to medical education of which he was proudest was his idea of clinical clerkship – having third- and fourth-year students work with patients on the wards.

He was instrumental in founding the Medical Library Association in North America, alongside employee and mentee Marcia Croker Noyes,[28] and served as its second president from 1901 to 1904.

Osler said Canada should be a "white man's country" in a 1914 speech given around the time of the Komagata Maru incident involving immigration from India.

[37][38] Under the pseudonym "Egerton Yorrick Davis", Osler mocked Indigenous people: "Every primitive tribe retains some vile animal habit not yet eliminated in the upward march of the race.

"[39] Uncovering this historical context, the journalists David Bruser and Markus Grill and the archivist Nils Seethaler reconstruct the shipment of several indigenous skulls by Osler from Canada to Germany, which were (previously unknown) in the custody of the State Museums of Berlin.

Osler, who had a well-developed humorous side to his character, was in his mid-fifties when he gave the speech and in it he mentioned Anthony Trollope's The Fixed Period (1882), which envisaged a college where men retired at 67 and after being given a year to settle their affairs, would be "peacefully extinguished by chloroform".

[42] The concept of mandatory euthanasia for humans after a "fixed period" (often 60 years) became a recurring theme in 20th century science fiction—for example, Isaac Asimov's 1950 novel Pebble in the Sky and Half a Life (Star Trek: The Next Generation).

An inveterate prankster, he wrote several humorous pieces under the pseudonym "Egerton Yorrick Davis", even fooling the editors of the Philadelphia Medical News into publishing a report on the extremely rare phenomenon of penis captivus, on December 13, 1884.

[45] Davis, a prolific writer of letters to medical societies, purported to be a retired U.S. Army surgeon living in Caughnawaga, Quebec (now Kahnawake), author of a fake paper on the obstetrical habits of Native American tribes that was intended as a joke on his rival, Dr. William A. Molson.

At the time of his death in August 1917, he was a second lieutenant in the (British) Royal Field Artillery;[47] Lt. Osler's grave is in the Dozinghem Military Cemetery in West Flanders, Belgium.

[48] According to one biographer, Osler was emotionally crushed by the loss; he was particularly anguished by the fact that his influence had been used to procure a military commission for his son, who had mediocre eyesight.

Osler was a founding donor of the American Anthropometric Society, a group of academics who pledged to donate their brains for scientific study.

![Arms of Osler of Toronto[19]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/95/Arms_of_Osler_of_Toronto.png/80px-Arms_of_Osler_of_Toronto.png)

From left to right: William Henry Welch , William Stewart Halsted , William Osler, Howard Kelly