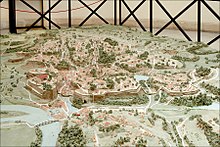

Plan of Rome (Bigot)

The Caen model, classified as a historic monument in 1978, has been the focus of dedicated work since the mid-1990s to create a virtual counterpart accessible to the public, integrating current knowledge about ancient Rome's topography.

[21] To support his hypotheses, Bigot conducted archaeological excavations funded by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres,[22] publishing the results and drawing analogies with other structures, such as the Circus of Maxentius.

The enthusiastic reception of this initial work, regarded from the start as "an impressive piece for the vivid image it provides of the ancient city,"[22] encouraged him to embark on a project that would ultimately occupy 40 years of his life.

To convey the building's scale, he then modeled the surrounding district, the city center, and eventually most of Rome[29] (excluding the Baths of Diocletian and the Vatican) with a visionary approach that might no longer be evident today.

This technique had been developed extensively in France from 1668 under the initiative of Louis XIV's minister Louvois, primarily for military purposes, representing the kingdom’s major fortified places at a scale of 1/600.

[37] The first modern models of Rome appeared at the end of the 18th century, made of cork or plaster,[38][39] intended for wealthy tourists or collectors like Louis-François-Sébastien Fauvel and Louis-François Cassas.

From 1860, scholarship recipients were divided between scientific ambitions and a desire for freedom from the Académie des Beaux-Arts' strict rules requiring depictions of the current state and a restored version of a monument.

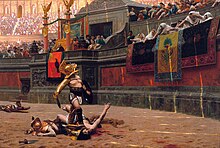

[43] The inclusion of "atmospheric reconstructions" as annexes to their submissions allowed architects to break free and present realistic scenes, which were popular at the time, inspired by artists like Théodore Chassériau, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

[44] Paul Bigot belongs to the "tradition of architect-archaeologists,"[45] and his work stands at the crossroads of the envois de Rome from the 19th and 20th centuries, situated between studies of monument complexes and those focused on colonial cities such as Selinunte, Priene, or Pompeii.

[49] For the residents of the Villa Medici, their Roman stay was a "rediscovery of planned urbanism," distinguishing between two types of cities: newly founded ones and those "shaped by the slow work of time.

[58] This period also saw significant contributions from Rodolfo Lanciani, who published numerous popular works in French and English,[54] as well as the more scientific Forma Urbis, a "turning point in Roman cartography,"[59] from 1893 to 1901.

[78] He made one final trip to Rome in 1934,[79] supported by a new subsidy,[78] to stay informed about recent discoveries related to major projects undertaken in the 1930s, particularly the construction of the Via dei Fori Imperiali, inaugurated on April 9, 1932, between the forums of Caesar and Augustus.

That same year, the Il Plastico model by Gismondi was exhibited in Rome[79] at the Mostra Augustea della Romanità, a show initiated by art historian and fascist party deputy Giulio Quirino Giglioli.

[97] Appointed a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1923 and head of a studio two years later,[24] Bigot, who was also the architect for French historical buildings [fr], collaborated with the Christofle silversmith company to create a bronze casting of the Plan of Rome.

Upon returning from captivity in Germany, Henry Bernard found two complete models in the Grand Palais rotunda,[92] one of which was donated to the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels and the other to the University of Caen.

[77] The donation to the Norman University was contingent upon the allocation of a specific space under the large amphitheaters of the law and literature faculties, which was accepted by deans Yver, Musset, and de Boüard [fr].

The installation, inaugurated on April 28, 1958,[108] included a sound and light show with illumination of the various monuments represented, along with explanations provided by Hellenist Henri Van Effenterre [fr] and historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet.

"[47] François Hinard rediscovered the work after his appointment as a professor of Roman history in 1983 and raised public and official awareness, reactivating the Association of Friends of the Plan of Rome.

The Plan of Rome at his disposal, a casting dated 1937 and exhibited at the Palais de Chaillot according to Royo, was modified by Bigot until his death[115] and intended solely for educational purposes.

[191] Lanciani's work on the Forma Urbis — the marble map was represented by Bigot in its original location on the wall of the Forum of Peace on his model[192][193] — was fundamental to his approach,[194] which later inspired Gismondi.

[214] He selected the same period as Giuseppe Gatteschi [fr] (1862-1935) for his restoration drawings of ancient Rome, placed in parallel to contemporary states, a work that took thirty years and was based on sources,[215] some of which dated back to the early 19th century.

[226] The desire for updating is responsible for the failure to transform the plan into bronze, as the Christofle company was "exasperated by Paul Bigot's meticulous perfectionism and the extra costs it entailed.

Nevertheless, he did modify the sector in the last version of his model, with treatment given to the House of Augustus and the Temple of the Vigna Barberini, leading to relocations of monuments and raising still-relevant questions.

[301] Paul Bigot's scientific and educational work inspired[302] or was imitated by the architect and archaeologist Italo Gismondi, but commissioned by Mussolini for propaganda purposes,[84] combining "antiquity and the present day, models and real constructions.

[304] Gismondi's model aligns with the fascist vision of the grandeur of Rome, serving "as an ideal reference and substitute for reality,"[304] and allowing for the extrapolation of incomplete archaeological research (such as the imperial forums, interrupted by the construction of the major axis that bears its name) or preserving the memory of destroyed elements, like those on the Velia.

[305] Exhibited at the Esposizione Universale di Roma (EUR) in the Museum of Roman Civilization, intended for the World’s Fair planned for 1942,[309] the Italian model, called Il Plastico, is larger (1/250 scale)[79] and depicts the entirety of ancient Rome.

[310] A project to restore Region XIV was under consideration in the early 1990s, as well as the creation of "a true and authentic digital map of ancient Rome" to establish a database and create "an illustrated manual for everyone.

[325] The team's work aims to propose architectural and topographical hypotheses, including mechanical systems related to buildings in use during the Roman era (velum, stage curtain, etc.).

"[344] The advantages of the virtual model are numerous and have been listed by Françoise Lecocq: in addition to the use of different scales for visits, it can also take place inside the reconstructed buildings; the visit takes place in a virtual world; multiple chronological levels can be reconstructed; the model is "evolving and reversible"; links allow for reference to sources or any interesting elements; the insertion of characters is possible; all the senses can be evoked.

[5] The scenography of the model in the new environment of the Maison de la Recherche en Sciences Humaines allows for visits by various audiences, including schools, with educational resources available for teachers.