Vitruvius

He states that all buildings should have three attributes: firmitas, utilitas, and venustas ("strength", "utility", and "beauty"),[3] principles reflected in much Ancient Roman architecture.

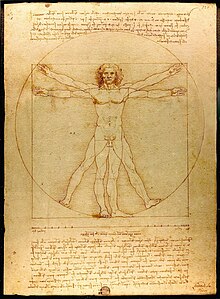

His discussion of perfect proportion in architecture and the human body led to the famous Renaissance drawing of the Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci.

Vitruvius' De architectura was well-known and widely copied in the Middle Ages and survives in many dozens of manuscripts,[6] though in 1414 it was "rediscovered" by the Florentine humanist Poggio Bracciolini in the library of Saint Gall Abbey.

Bramante, Michelangelo, Palladio, Vignola and earlier architects are known to have studied the work of Vitruvius, and consequently it has had a significant impact on the architecture of many European countries.

Vitruvius was a military engineer (praefectus fabrum), or a praefect architectus armamentarius of the apparitor status group (a branch of the Roman civil service).

He is mentioned in Pliny the Elder's table of contents for Naturalis Historia (Natural History), in the heading for mosaic techniques.

He had the charge of providing carriages, bathhouses and the proper tools for sawing and cutting wood, digging trenches, raising parapets, sinking wells and bringing water into the camp.

He likewise had the care of furnishing the troops with wood and straw, as well as the rams, onagri, balistae and all the other engines of war under his direction.

This post was always conferred on an officer of great skill, experience and long service, and who consequently was capable of instructing others in those branches of the profession in which he had distinguished himself.

In his work describing the construction of military installations, he also commented on the miasma theory – the idea that unhealthy air from wetlands was the cause of illness, saying: For fortified towns the following general principles are to be observed.

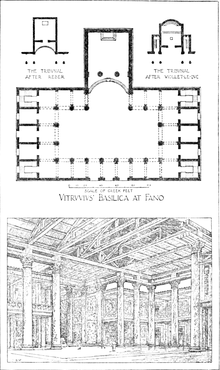

The Basilica di Fano (to give the building its Italian name) has disappeared so completely that its very site is a matter of conjecture, although various attempts have been made to visualise it.

In later years the emperor Augustus, through his sister Octavia Minor, sponsored Vitruvius, entitling him with what may have been a pension to guarantee financial independence.

[citation needed] Gerolamo Cardano, in his 1552 book De subtilitate rerum, ranks Vitruvius as one of the 12 persons whom he supposes to have excelled all men in the force of genius and invention; and might have given him first place if it was clear that he had set down his own discoveries.

[25] James Anderson's "The Constitutions of the Free-Masons" (1734), reprinted by Benjamin Franklin, describes Vitruvius as "the Father of all true Architects to this Day.

According to Petri Liukkonen, this text "influenced deeply from the Early Renaissance onwards artists, thinkers, and architects, among them Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), and Michelangelo (1475–1564).

However, we know there was a significant body of writing about architecture in Greek, where "architects habitually wrote books about their work", including two we know of about the Parthenon alone.

[28] Vitruvius is famous for asserting in his book De architectura that a structure must exhibit the three qualities of firmitatis, utilitatis, venustatis – that is, stability, utility, and beauty.

As birds and bees built their nests, so humans constructed housing from natural materials, that gave them shelter against the elements.

This led Vitruvius in defining his Vitruvian Man, as drawn later by Leonardo da Vinci: the human body inscribed in the circle and the square (the fundamental geometric patterns of the cosmic order).

Practice is the frequent and continued contemplation of the mode of executing any given work, or of the mere operation of the hands, for the conversion of the material in the best and readiest way.

[31]He goes on to say that the architect should be versed in drawing, geometry, optics (lighting), history, philosophy, music, theatre, medicine, and law.

[27] Implicitly challenging the reader that they have never heard of some of these people, Vitruvius goes on and predicts that some of these individuals will be forgotten and their works lost, while other, less deserving political characters of history will be forever remembered with pageantry.

[38] Translations followed in Italian (Cesare Cesariano, 1521), French (Jean Martin, 1547[39]), English, German (Walther H. Ryff, 1543) and Spanish and several other languages.

Filippo Brunelleschi, for example, invented a new type of hoist to lift the large stones for the dome of the cathedral in Florence and was inspired by De Architectura as well as surviving Roman monuments such as the Pantheon and the Baths of Diocletian.

Latin Italian French English Books VIII, IX and X form the basis of much of what we know about Roman technology, now augmented by archaeological studies of extant remains, such as the water mills at Barbegal in France.

He also describes the construction of sundials and water clocks, and the use of an aeolipile (the first steam engine) as an experiment to demonstrate the nature of atmospheric air movements (wind).

Vitruvius was writing in the 1st century BC when many of the finest Roman aqueducts were built, and survive to this day, such as those at Segovia and the Pont du Gard.

Vitruvius is cited as one of the earliest sources to connect lead mining and manufacture, its use in drinking water pipes, and its adverse effects on health.

They were essential in all building operations, but especially in aqueduct construction, where a uniform gradient was important to the provision of a regular supply of water without damage to the walls of the channel.

He also advises on using a type of regulator to control the heat in the hot rooms, a bronze disc set into the roof under a circular aperture which could be raised or lowered by a pulley to adjust the ventilation.