Nebular hypothesis

[1] It offered explanations for a variety of properties of the Solar System, including the nearly circular and coplanar orbits of the planets, and their motion in the same direction as the Sun's rotation.

[3] Initially very hot, the disk later cools in what is known as the T Tauri star stage; here, formation of small dust grains made of rocks and ice is possible.

[4] The accumulation of gas by the core is initially a slow process, which continues for several million years, but after the forming protoplanet reaches about 30 Earth masses (ME) it accelerates and proceeds in a runaway manner.

According to some, a major critique came during the 19th century from James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879), who in some sources is claimed to have maintained that different rotation between the inner and outer parts of a ring could not allow condensation of material.

[7] However, both the critique and the attribution to Maxwell have been deemed to be incorrect upon further investigation, with the original error being made by George Gamow in some popular publications and propagated continually ever since.

[9] Brewster claimed that Sir Isaac Newton's religious beliefs had previously considered nebular ideas as tending to atheism, and quoted him as saying that "the growth of new systems out of old ones, without the mediation of a Divine power, seemed to him apparently absurd".

The birth of the modern widely accepted theory of planetary formation—the solar nebular disk model (SNDM)—can be traced to the Soviet astronomer Victor Safronov.

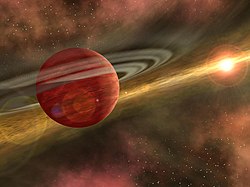

[1] While originally applied only to the Solar System, the SNDM was subsequently thought by theorists to be at work throughout the Universe; as of 26 January 2024 astronomers have discovered 7,408 extrasolar planets in our galaxy.

One possible explanation suggested by Hannes Alfvén was that angular momentum was shed by the solar wind during its T Tauri star phase.

Old theories were unable to explain how their cores could form fast enough to accumulate significant amounts of gas from the quickly disappearing protoplanetary disk.

Some calculations show that interaction with the disk can cause rapid inward migration, which, if not stopped, results in the planet reaching the "central regions still as a sub-Jovian object.

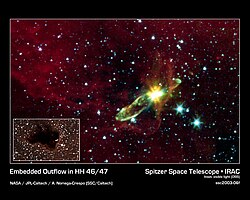

[2][38] As the collapse continues, conservation of angular momentum means that the rotation of the infalling envelope accelerates,[39][40] which largely prevents the gas from directly accreting onto the central core.

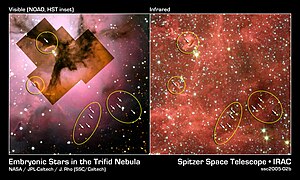

[38][42] As the infall of its material onto the disk continues, the envelope eventually becomes thin and transparent and the young stellar object (YSO) becomes observable, initially in far-infrared light and later in the visible.

[39][52] The result of this process is the growth of both the protostar and of the disk radius, which can reach 1,000 AU if the initial angular momentum of the nebula is large enough.

[19] The transport of the material from the outer disk can mix these newly formed dust grains with primordial ones, which contain organic matter and other volatiles.

This mixing can explain some peculiarities in the composition of Solar System bodies such as the presence of interstellar grains in primitive meteorites and refractory inclusions in comets.

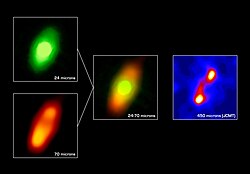

[2][54] Planetesimal formation is another unsolved problem of disk physics, as simple sticking becomes ineffective as dust particles grow larger.

[2][28] However, the differing velocities of the gas disk and the solids near the mid-plane can generate turbulence which prevents the layer from becoming thin enough to fragment due to gravitational instability.

[56] Another possible mechanism for the formation of planetesimals is the streaming instability in which the drag felt by particles orbiting through gas creates a feedback effect causing the growth of local concentrations.

[58] If these clumps migrate inward as the collapse proceeds tidal forces from the star can result in a significant mass loss leaving behind a smaller body.

Meteorites are samples of planetesimals that reach a planetary surface, and provide a great deal of information about the formation of the Solar System.

The oligarchs are kept at the distance of about 10·Hr (Hr=a(1-e)(M/3Ms)1/3 is the Hill radius, where a is the semimajor axis, e is the orbital eccentricity, and Ms is the mass of the central star) from each other by the influence of the remaining planetesimals.

[62] Rocky planets which have managed to coalesce settle eventually into more or less stable orbits, explaining why planetary systems are generally packed to the limit; or, in other words, why they always appear to be at the brink of instability.

[65] An additional difference is the composition of the planetesimals, which in the case of giant planets form beyond the so-called frost line and consist mainly of ice—the ice to rock ratio is about 4 to 1.

However, the minimum mass nebula capable of terrestrial planet formation can only form 1–2 ME cores at the distance of Jupiter (5 AU) within 10 million years.

The post-runaway-gas-accretion stage is characterized by migration of the newly formed giant planets and continued slow gas accretion.

The presence of giants tends to increase eccentricities and inclinations (see Kozai mechanism) of planetesimals and embryos in the terrestrial planet region (inside 4 AU in the Solar System).

If they form near the end of the oligarchic stage, as is thought to have happened in the Solar System, they will influence the merges of planetary embryos, making them more violent.

The absence of Super-Earths and closely orbiting planets in the Solar System may be due to the previous formation of Jupiter blocking their inward migration.

In this context, accretion refers to the process of cooled, solidified grains of dust and ice orbiting the protostar in the protoplanetary disk, colliding and sticking together and gradually growing, up to and including the high-energy collisions between sizable planetesimals.