Plant disease resistance

Plant disease resistance is crucial to the reliable production of food, and it provides significant reductions in agricultural use of land, water, fuel, and other inputs.

The world's first mass-cultivated banana cultivar Gros Michel was lost in the 1920s to Panama disease caused by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum.

Other epidemics include chestnut blight, as well as recurrent severe plant diseases such as rice blast, soybean cyst nematode, and citrus canker.

Activation of PRRs leads to intracellular signaling, transcriptional reprogramming, and biosynthesis of a complex output response that limits colonization.

ETI is typically activated by the presence of specific pathogen "effectors" and then triggers strong antimicrobial responses (see R gene section below).

Individual R genes have been demonstrated to mediate resistance to specific virus, bacteria, oomycete, fungus, nematode or insect strains.

Well-studied bacterial plant pathogens typically express a few dozen effectors, often delivered into the host by a Type III secretion apparatus.

[18][19] Advances in genome‐wide studies revealed a massive adaptation of host miRNA expression patterns after infection by fungal pathogens Fusarium virguliforme,[20] Erysiphe graminis,[21] Verticillium dahliae,[22] and Cronartium quercuum,[23] and the oomycete Phytophthora sojae.

[24] Changes to sRNA expression in response to fungal pathogens indicate that gene silencing may be involved in this defense pathway.

[28] There is also evidence that plant EVs can allow for interspecies transfer of sRNAs by RNA interference such as Host-Induced Gene Silencing (HIGS).

[29][30] The transport of RNA between plants and fungi seems to be bidirectional as sRNAs from the fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea have been shown to target host defense genes in Arabidopsis and tomato.

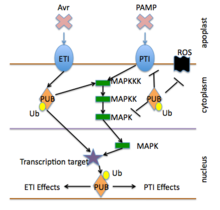

Examples:[36] Ubiquitination plays a central role in cell signaling that regulates processes including protein degradation and immunological response.

[37] Although one of the main functions of ubiquitin is to target proteins for destruction, it is also useful in signaling pathways, hormone release, apoptosis and translocation of materials throughout the cell.

Without ubiquitin's proper functioning, the invasion of pathogens and other harmful molecules would increase dramatically due to weakened immune defenses.

Horizontal or broad-spectrum resistance against an entire pathogen species is often only incompletely effective, but more durable, and is often controlled by many genes that segregate in breeding populations.

[47][48] Crops such as potato, apple, banana, and sugarcane are often propagated by vegetative reproduction to preserve highly desirable plant varieties, because for these species, outcrossing seriously disrupts the preferred traits.

[50] Combining coat protein genes from three different viruses, scientists developed squash hybrids with field-validated, multiviral resistance.

No other crop with engineered disease resistance against microbial pathogens had reached the market by 2013, although more than a dozen were in some state of development and testing.

Identification of functional PRRs and their transfer to a recipient species that lacks an orthologous receptor could provide a general pathway to additional broadened PRR repertoires.

Research performed at Sainsbury Laboratory demonstrated that deployment of EFR into either Nicotiana benthamiana or Solanum lycopersicum (tomato), which cannot recognize EF-Tu, conferred resistance to a wide range of bacterial pathogens.

The first “effector-rationalized” search for a potentially durable R gene followed the finding that avrBs2 is found in most disease-causing Xanthomonas species and is required for pathogen fitness.

[1] Another class of plant disease resistance genes opens a “trap door” that quickly kills invaded cells, stopping pathogen proliferation.

Xanthomonas and Ralstonia transcription activator–like (TAL) effectors are DNA-binding proteins that activate host gene expression to enhance pathogen virulence.

Both the rice and pepper lineages independently evolved TAL-effector binding sites that instead act as an executioner that induces hypersensitive host cell death when up-regulated.

[1] Engineered executor genes were demonstrated by successfully redesigning the pepper Bs3 promoter to contain two additional binding sites for TAL effectors from disparate pathogen strains.

For example, a mutation disabled an Arabidopsis gene encoding pectate lyase (involved in cell wall degradation), conferring resistance to the powdery mildew pathogen Golovinomyces cichoracearum.

[1] Xa13/Os-8N3 is required for pollen development, showing that such mutant alleles can be problematic should the disease-susceptibility phenotype alter function in other processes.

Similarly, Capsicum chinense plants carrying the Tsw gene can become systemically infected with Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) at 32°C.

[57] Monocrop agricultural systems provide an ideal environment for pathogen evolution, because they offer a high density of target specimens with similar/identical genotypes.

Some pathogen species have much greater capacity to overcome plant disease resistance than others, often because of their ability to evolve rapidly and to disperse broadly.