Plasmid

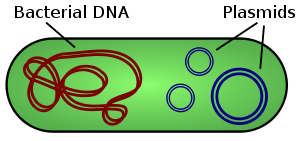

They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; however, plasmids are sometimes present in archaea and eukaryotic organisms.

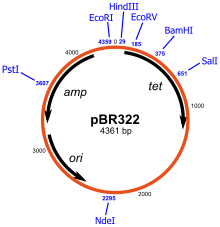

[1][page needed][2] Plasmids often carry useful genes, such as those involved in antibiotic resistance, virulence,[3][4][5] secondary metabolism[6] and bioremediation.

[7][8] While chromosomes are large and contain all the essential genetic information for living under normal conditions, plasmids are usually very small and contain additional genes for special circumstances.

Artificial plasmids are widely used as vectors in molecular cloning, serving to drive the replication of recombinant DNA sequences within host organisms.

Unlike viruses, which encase their genetic material in a protective protein coat called a capsid, plasmids are "naked" DNA and do not encode genes necessary to encase the genetic material for transfer to a new host; however, some classes of plasmids encode the conjugative "sex" pilus necessary for their own transfer.

The term plasmid was coined in 1952 by the American molecular biologist Joshua Lederberg to refer to "any extrachromosomal hereditary determinant.

A typical bacterial replicon may consist of a number of elements, such as the gene for plasmid-specific replication initiation protein (Rep), repeating units called iterons, DnaA boxes, and an adjacent AT-rich region.

Some of these genes encode traits for antibiotic resistance or resistance to heavy metal, while others may produce virulence factors that enable a bacterium to colonize a host and overcome its defences or have specific metabolic functions that allow the bacterium to utilize a particular nutrient, including the ability to degrade recalcitrant or toxic organic compounds.

[20] However, recent studies show that they may play a role in antibiotic resistance by contributing to heteroresistance within bacterial populations.

These elements carry core genes and have codon usage similar to the chromosome, yet use a plasmid-type replication mechanism such as the low copy number RepABC.

These plasmids serve as important tools in genetics and biotechnology labs, where they are commonly used to clone and amplify (make many copies of) or express particular genes.

DNA structural instability can be defined as a series of spontaneous events that culminate in an unforeseen rearrangement, loss, or gain of genetic material.

Accessory regions pertaining to the bacterial backbone may engage in a wide range of structural instability phenomena.

Well-known catalysts of genetic instability include direct, inverted, and tandem repeats, which are known to be conspicuous in a large number of commercially available cloning and expression vectors.

[38] Insertion sequences can also severely impact plasmid function and yield, by leading to deletions and rearrangements, activation, down-regulation or inactivation of neighboring gene expression.

[39] Therefore, the reduction or complete elimination of extraneous noncoding backbone sequences would pointedly reduce the propensity for such events to take place, and consequently, the overall recombinogenic potential of the plasmid.

Zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) offer a way to cause a site-specific double-strand break to the DNA genome and cause homologous recombination.

Plasmids encoding ZFN could help deliver a therapeutic gene to a specific site so that cell damage, cancer-causing mutations, or an immune response is avoided.

However, developments in adeno-associated virus recombination techniques, and zinc finger nucleases, have enabled the creation of a new generation of isogenic human disease models.

[48] A benefit of using plasmids to transfer BGC is demonstrated by using a suitable host that can mass produce specialized metabolites, some of these molecules are able to control microbial population.

[50] BGC's can also be transfers to the host organism's chromosome, utilizing a plasmid vector, which allows for studies in gene knockout experiments.

[52] The term episome was introduced by François Jacob and Élie Wollman in 1958 to refer to extra-chromosomal genetic material that may replicate autonomously or become integrated into the chromosome.

[57] In the context of eukaryotes, the term episome is used to mean a non-integrated extrachromosomal closed circular DNA molecule that may be replicated in the nucleus.

Episomes in eukaryotes behave similarly to plasmids in prokaryotes in that the DNA is stably maintained and replicated with the host cell.

Some episomes, such as herpesviruses, replicate in a rolling circle mechanism, similar to bacteriophages (bacterial phage viruses).

When these viral episomes initiate lytic replication to generate multiple virus particles, they generally activate cellular innate immunity defense mechanisms that kill the host cell.

[63] Circular plasmids have been isolated and found in many different plants, with those in Vicia faba and Chenopodium album being the most studied and whose mechanism of replication is known.

The yield is a small amount of impure plasmid DNA, which is sufficient for analysis by restriction digest and for some cloning techniques.

These programs record the DNA sequence of plasmid vectors, help to predict cut sites of restriction enzymes, and to plan manipulations.

Examples of software packages that handle plasmid maps are ApE, Clone Manager, GeneConstructionKit, Geneious, Genome Compiler, LabGenius, Lasergene, MacVector, pDraw32, Serial Cloner, UGENE, VectorFriends, Vector NTI, and WebDSV.