Plesiosaur

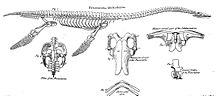

Their limbs had evolved into four long flippers, which were powered by strong muscles attached to wide bony plates formed by the shoulder girdle and the pelvis.

[8] In 1605, Richard Verstegen of Antwerp illustrated in his A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence plesiosaur vertebrae that he referred to fishes and saw as proof that Great Britain was once connected to the European continent.

[10] Other naturalists during the seventeenth century added plesiosaur remains to their collections, such as John Woodward; these were only much later understood to be of a plesiosaurian nature and are today partly preserved in the Sedgwick Museum.

Important collectors were the reverends William Mounsey and Baptist Noel Turner, active in the Vale of Belvoir, whose collections were in 1795 described by John Nicholls in the first part of his The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicestershire.

[12] One of Turner's partial plesiosaur skeletons is still preserved as specimen NHMUK PV R.45 (formerly BMNH R.45) in the British Museum of Natural History; this is today referred to Thalassiodracon.

The generic name was derived from the Ancient Greek πλήσιος, plèsios, "closer to" and the Latinised saurus, in the meaning of "saurian", to express that Plesiosaurus was in the Chain of Being more closely positioned to the Sauria, particularly the crocodile, than Ichthyosaurus, which had the form of a more lowly fish.

In 1823, Thomas Clark reported an almost complete skull, probably belonging to Thalassiodracon, which is now preserved by the British Geological Survey as specimen BGS GSM 26035.

[26] Excited, Cope concluded to have discovered an entirely new group of reptiles: the Streptosauria or "Turned Saurians", which would be distinguished by reversed vertebrae and a lack of hindlimbs, the tail providing the main propulsion.

[27] After having published a description of this animal,[28] followed by an illustration in a textbook about reptiles and amphibians,[29] Cope invited Marsh and Joseph Leidy to admire his new Elasmosaurus platyurus.

Some of this is taking place away from the traditional areas, e.g. in new sites developed in New Zealand, Argentina, Chile,[37] Norway, Japan, China and Morocco, but the locations of the more original discoveries have proven to be still productive, with important new finds in England and Germany.

Other adaptations allowing them to colonise the open seas included stiff limb joints; an increase in the number of phalanges of the hand and foot; a tighter lateral connection of the finger and toe phalanx series, and a shortened tail.

[51][52] From the earliest Jurassic, the Hettangian stage, a rich radiation of plesiosaurs is known, implying that the group must already have diversified in the Late Triassic; of this diversification, however, only a few (very) basal forms have been discovered, the most derived Rhaeticosaurus.

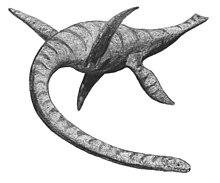

By the Toarcian, about 180 million years ago, other groups, among them the Plesiosauridae, became more numerous and some species developed longer necks, resulting in total body lengths of up to ten metres (33 feet).

Later in the Early Cretaceous, the Elasmosauridae appeared; these were among the longest plesiosaurs, reaching up to fifteen metres (fifty feet) in length due to very long necks containing as many as 76 vertebrae, more than any other known vertebrate.

[55] At the beginning of the Late Cretaceous, the Ichthyosauria became extinct; perhaps a plesiosaur group evolved to fill their niches: the Polycotylidae, which had short necks and peculiarly elongated heads with narrow snouts.

Plesiosauria was in 2010 by Hillary Ketchum and Roger Benson defined as such a stem-based taxon: "all taxa more closely related to Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus and Pliosaurus brachydeirus than to Augustasaurus hagdorni".

Ketchum and Benson (2010) also coined a new clade Neoplesiosauria, a node-based taxon that was defined by as "Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus, Pliosaurus brachydeirus, their most recent common ancestor and all of its descendants".

[55] The clade Neoplesiosauria very likely is materially identical to Plesiosauria sensu Druckenmiller & Russell, thus would designate exactly the same species, and the term was meant to be a replacement of this concept.

The group thus contained some of the largest marine apex predators in the fossil record, roughly equalling the longest ichthyosaurs, mosasaurids, sharks and toothed whales in size.

[65] To power the flippers, the shoulder girdle and the pelvis had been greatly modified, developing into broad bone plates at the underside of the body, which served as an attachment surface for large muscle groups, able to pull the limbs downwards.

However, modern research has confirmed an earlier conjecture of Williston that the long plate-like spines on top of the vertebrae, the processus spinosi, strongly limited vertical neck movement.

The upper temporal fenestrae formed large openings at the sides of the rear skull roof, the attachment for muscles closing the lower jaws.

In the early twentieth century, the newly discovered principles of bird flight suggested to several researchers that plesiosaurs, like turtles and penguins, made a flying movement while swimming.

During both strokes, down and up, according to Bernoulli's principle, forward and upward thrust is generated by the convexly curved upper profile of the flipper, the front edge slightly inclined relative to the water flow, while turbulence is minimal.

However, despite the evident advantages of such a swimming method, in 1924 the first systematic study on the musculature of plesiosaurs by David Meredith Seares Watson concluded they nevertheless performed a rowing movement.

In 1957, Lambert Beverly Halstead, at the time using the family name Tarlo, proposed a variant: the hindlimbs would have rowed in the horizontal plane but the forelimbs would have paddled, moved to below and to the rear.

They proposed a more limited flying model in which a powerful downstroke was combined with a largely unpowered recovery, the flipper returning to its original position by the momentum of the forward moving and temporarily sinking body.

The vertebrae show no such damage: they were probably protected by a superior blood supply, made possible by the arteries entering the bone through the two foramina subcentralia, large openings in their undersides.

[124] However, these results are problematic in view of general principles of vertebrate physiology (see Kleiber's law); evidence from isotope studies of plesiosaur tooth enamel indeed suggests endothermy at lower RMRs, with inferred body temperatures of ca.

However, as those limbs no longer had functional elbow or knee joints and the underside by its very flatness would have generated a lot of friction, already in the nineteenth century it was hypothesised that plesiosaurs had been viviparous.