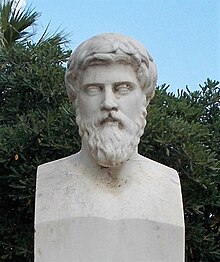

Plutarch

[3][a] Plutarch was born to a prominent family in the small town of Chaeronea,[4] about 30 kilometres (19 mi) east of Delphi, in the Greek region of Boeotia.

[6] As a Roman citizen, Plutarch would have been of the equestrian order, he visited Rome some time c. AD 70 with Florus, who served also as a historical source for his Life of Otho.

[7][6] Plutarch was on familiar terms with a number of Roman nobles, particularly the consulars Quintus Sosius Senecio, Titus Avidius Quietus, and Arulenus Rusticus, all of whom appear in his works.

[10] Some time c. AD 95, Plutarch was made one of the two sanctuary priests for the temple of Apollo at Delphi; the site had declined considerably since the classical Greek period.

[3] The portrait of a philosopher exhibited at the exit of the Archaeological Museum of Delphi, dates to the 2nd century; due to its inscription, in the past it had been identified with Plutarch.

[13] In addition to his duties as a priest of the Delphic temple, Plutarch was also a magistrate at Chaeronea and he represented his home town on various missions to foreign countries during his early adult years.

[17][page needed] According to the 8th/9th-century historian George Syncellus, late in Plutarch's life, Emperor Hadrian appointed him nominal procurator of Achaea – which entitled him to wear the vestments and ornaments of a consul.

A letter is still extant, addressed by Plutarch to his wife, bidding her not to grieve too much at the death of their two-year-old daughter, who was named Timoxena after her mother, which also mentions the loss of a young son, Chaeron.

[27] Plutarch's best-known work is the Parallel Lives, a series of biographies of illustrious Greeks and Romans, arranged in pairs to illuminate their common moral virtues and vices, thus it being more of an insight into human nature than a historical account.

As is explained in the opening paragraph of his Life of Alexander,[28] Plutarch was not concerned with history so much as the influence of character, good or bad, on the lives and destinies of men.

Whereas sometimes he barely touched on epoch-making events, he devoted much space to charming anecdote and incidental triviality, reasoning that this often said far more for his subjects than even their most famous accomplishments.

He sought to provide rounded portraits, likening his craft to that of a painter; indeed, he went to tremendous lengths (often leading to tenuous comparisons) to draw parallels between physical appearance and moral character.

[citation needed] Extant Lives include those on Solon, Themistocles, Aristides, Agesilaus II, Pericles, Alcibiades, Nicias, Demosthenes, Pelopidas, Philopoemen, Timoleon, Dion of Syracuse, Eumenes, Alexander the Great, Pyrrhus of Epirus, Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Coriolanus, Theseus, Aemilius Paullus, Tiberius Gracchus, Gaius Gracchus, Gaius Marius, Sulla, Sertorius, Lucullus, Pompey, Julius Caesar, Cicero, Cato the Elder, Cato the Younger, Mark Antony, and Marcus Junius Brutus.

"It is not histories I am writing, but lives; and in the most glorious deeds there is not always an indication of virtue or vice, indeed a small thing like a phrase or a jest often makes a greater revelation of a character than battles where thousands die."

It includes anecdotes and descriptions of events that appear in no other source, just as Plutarch's portrait of Numa Pompilius, the putative second king of Rome, holds much that is unique on the early Roman calendar.

He also draws extensively on the work of Lysippos, Alexander's favourite sculptor, to provide what is probably the fullest and most accurate description of the conqueror's physical appearance.

When it comes to his character, Plutarch emphasizes his unusual degree of self-control and scorn for luxury: "He desired not pleasure or wealth, but only excellence and glory."

It is an eclectic collection of seventy-eight essays and transcribed speeches, including "Concerning the Face Which Appears in the Orb of the Moon" (a dialogue on the possible causes for such an appearance and a source for Galileo's own work),[31] "On Fraternal Affection" (a discourse on honour and affection of siblings toward each other), "On the Fortune or the Virtue of Alexander the Great" (an important adjunct to his Life of the great king), and "On the Worship of Isis and Osiris" (a crucial source of information on ancient Egyptian religion);[32] more philosophical treatises, such as "On the Decline of the Oracles", "On the Delays of the Divine Vengeance", and "On Peace of Mind"; and lighter fare, such as "Odysseus and Gryllus", a humorous dialogue between Homer's Odysseus and one of Circe's enchanted pigs.

Galba-Otho can be found in the appendix to Plutarch's Parallel Lives as well as in various Moralia manuscripts, most prominently in Maximus Planudes' edition where Galba and Otho appear as Opera XXV and XXVI.

[38][39] Lost works that would have been part of the Moralia include "Whether One Who Suspends Judgment on Everything Is Condemned to Inaction", "On Pyrrho's Ten Modes", and "On the Difference between the Pyrrhonians and the Academics".

[41] However pure Plutarch's idea of God is, and however vivid his description of the vice and corruption which superstition causes, his warm religious feelings and his distrust of human powers of knowledge led him to believe that God comes to our aid by direct revelations, which we perceive the more clearly the more completely that we refrain in "enthusiasm" from all action; this made it possible for him to justify popular belief in divination in the way which had long been usual among the Stoics.

In 1519, Hieronymus Emser translated De capienda ex inimicis utilitate (wie ym eyner seinen veyndt nutz machen kan, Leipzig).

Montaigne's Essays draw extensively on Plutarch's Moralia and are consciously modelled on the Greek's easygoing and discursive inquiries into science, manners, customs and beliefs.

He went to Italy and studied the Vatican text of Plutarch, from which he published a French translation of the Lives in 1559 and Moralia in 1572, which were widely read by educated Europe.

Ralph Waldo Emerson and the transcendentalists were greatly influenced by the Moralia and in his glowing introduction to the five-volume, 19th-century edition, he called the Lives "a bible for heroes".

[49] Other admirers included Ben Jonson, Alexander Hamilton, John Milton, Edmund Burke, Joseph De Maistre, Mark Twain, Louis L'amour, and Francis Bacon, as well as such disparate figures as Cotton Mather and Robert Browning.