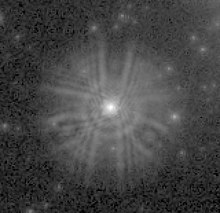

Point spread function

The PSF in many contexts can be thought of as the shapeless blob in an image that should represent a single point object.

The images of the individual object-plane impulse functions are called point spread functions (PSF), reflecting the fact that a mathematical point of light in the object plane is spread out to form a finite area in the image plane.

In microscope image processing and astronomy, knowing the PSF of the measuring device is very important for restoring the (original) object with deconvolution.

[2] The point spread function may be independent of position in the object plane, in which case it is called shift invariant.

With these two assumptions, i.e., that the PSF is shift-invariant and that there is no distortion, calculating the image plane convolution integral is a straightforward process.

The utility of the point source concept comes from the fact that a point source in the 2D object plane can only radiate a perfect uniform-amplitude, spherical wave — a wave having perfectly spherical, outward travelling phase fronts with uniform intensity everywhere on the spheres (see Huygens–Fresnel principle).

We also note that a perfect point source radiator will not only radiate a uniform spectrum of propagating plane waves, but a uniform spectrum of exponentially decaying (evanescent) waves as well, and it is these which are responsible for resolution finer than one wavelength (see Fourier optics).

This follows from the following Fourier transform expression for a 2D impulse function, The quadratic lens intercepts a portion of this spherical wave, and refocuses it onto a blurred point in the image plane.

It can be shown (see Fourier optics, Huygens–Fresnel principle, Fraunhofer diffraction) that the field radiated by a planar object (or, by reciprocity, the field converging onto a planar image) is related to its corresponding source (or image) plane distribution via a Fourier transform (FT) relation.

That is, a uniformly-illuminated circular aperture that passes a converging uniform spherical wave yields an Airy disk image at the focal plane.

Therefore, the converging (partial) spherical wave shown in the figure above produces an Airy disc in the image plane.

In other words, if Θmax is small, the Airy disc is large (which is just another statement of Heisenberg's uncertainty principle for Fourier Transform pairs, namely that small extent in one domain corresponds to wide extent in the other domain, and the two are related via the space-bandwidth product).

By virtue of this, high magnification systems, which typically have small values of Θmax (by the Abbe sine condition), can have more blur in the image, owing to the broader PSF.

Due to intrinsic limited resolution of the imaging systems, measured PSFs are not free of uncertainty.

The diffraction theory of point spread functions was first studied by Airy in the nineteenth century.

He developed an expression for the point spread function amplitude and intensity of a perfect instrument, free of aberrations (the so-called Airy disc).

The theory of aberrated point spread functions close to the optimum focal plane was studied by Zernike and Nijboer in the 1930–40s.

A central role in their analysis is played by Zernike's circle polynomials that allow an efficient representation of the aberrations of any optical system with rotational symmetry.

The ENZ-theory has also been applied to the characterization of optical instruments with respect to their aberration by measuring the through-focus intensity distribution and solving an appropriate inverse problem.

In microscopy, experimental determination of PSF requires sub-resolution (point-like) radiating sources.

[6][7] Theoretical models as described above, on the other hand, allow the detailed calculation of the PSF for various imaging conditions.

In observational astronomy, the experimental determination of a PSF is often very straightforward due to the ample supply of point sources (stars or quasars).

A complete description of the PSF will also include diffusion of light (or photo-electrons) in the detector, as well as tracking errors in the spacecraft or telescope.

This, in conjunction with a CCD camera and an adaptive optics system, can be used to visualize anatomical structures not otherwise visible in vivo, such as cone photoreceptors.