Polacanthus

indicated two possible unique traits, autapomorphies: the floor of the neural canal is deeply cut by a groove with a V-shaped transverse profile; the caudal spikes have triangular bases in side view and narrow points.

[8] In 2020, a study concluded to a single autapomorphy: the ischia at half length curve towards each other, their rear ends touching at their inner sides.

Polacanthus foxii was discovered by the Reverend William Fox on the Isle of Wight in early 1865, at Barnes High at the southwest coast.

Fox at first planned to have his friend Alfred Tennyson name the new dinosaur during a meeting on 23 July 1865, when the remains were shown to paleontologist Richard Owen.

[13] The text of the lecture, only published in 1866, was more or less reproduced by him in anonymous articles in the Geological Magazine and the Illustrated London News of 16 September 1865.

The generic name is derived from Greek πολύς, polys, "many" and ἄκανθα, akantha, "thorn", in reference to the many spikes of the armour.

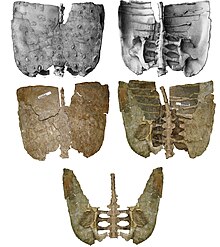

It is an incomplete skeleton with the head, neck, anterior armour and forelimbs missing but including dorsal vertebrae, a sacral rod of five dorsosacrals, the sacrum, most of the pelvis, most of the left hindleg, the right thighbone, twenty-two tail vertebrae, ribs, chevrons, ossified tendons, a pelvic shield, twenty-two spikes and numerous ossicles.

Hulke published the first detailed description of the find, noting that the specimen had badly deteriorated over the years, the dermal armour having almost fully fallen apart.

[17] The same year Fox died, his collection was acquired by the British Museum of Natural History, including the Polacanthus fossil.

This was after arrival in the museum in 1882, reassembled by preparator Caleb Barlow, painstakingly putting all the pieces together with Canada balsam, much to the wonder of Hulke who in 1881 had called this a hopeless undertaking.

[10] In 1905, when it was mounted by the museum, the specimen was again described by Franz Nopcsa who for the first time provided an illustration of the possible spike configuration.

[18] In 1859, geologist Ernest P. Wilkins mentioned the presence in his collection of numerous scutes, spikes and vertebrae from Wight, referred by him to Hylaeosaurus.

A second partial skeleton, from which parts had been removed since 1876, was identified and fully excavated by Dr. William T. Blows in 1979;[20] it is also in the London Natural History Museum as specimen NHMUK R9293.

In 2014 a partial skeleton was reported from Bexhill in Sussex, specimen BEXHM 1999.34.1-2011.23.1 discovered in the early summer of 1998 by David Brockhurst in the Ashdown Pevensey Quarry.

[22][23][24] A 2020 review of British ankylosaurian fossils concluded that none of these additional specimens could be confidently referred to Polacanthus, which would therefore be represented only by the holotype.

In 1996, a Polacanthus rudgwickensis was named by Blows,[27] after a review of some fossil material found in 1985 and thought to have been Iguanodon, which was on display at the Horsham Museum in Sussex.

The material, holotype HORSM 1988.1546, is fragmentary and includes several incomplete vertebrae, a partial scapulocoracoid, the distal end of a humerus, a nearly complete right tibia, rib fragments, and two osteoderms.

P. rudgwickensis seems to have been about 30% longer than type species P. foxii and differs from it in numerous characters of the vertebrae and dermal armour.

[35] An alternative hypothesis, first suggested by Tracy Lee Ford in 2000,[36] is that there existed a clade Polacanthidae below the Nodosauridae + Ankylosauridae node.