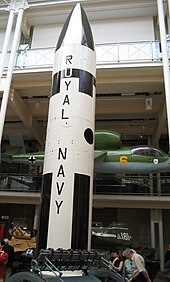

UGM-27 Polaris

A crash program to develop a missile suitable for carrying such warheads began as Polaris, launching its first shot less than four years later, in February 1960.

This led to new infighting between the Navy and the U.S. Air Force, the latter responding by developing the counterforce concept that argued for the strategic bomber and ICBM as key elements in flexible response.

[8] On September 13, 1955, James R. Killian, head of a special committee organized by President Eisenhower, recommended that both the Army and Navy come together under a program aimed at developing an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM).

The two knew each other well: Mark was named head of the theoretical division of Los Alamos in 1947, a job that was originally offered for Teller.

[13] Almost four decades later, Teller said, referring to Mark's performance, that it was “an occasion when I was happy about the other person being bashful.”[13] When the Atomic Energy Commission backed up Teller's estimate in early September, Admiral Burke and the Navy Secretariat decided to support SPO in heavily pushing for the new missile, now named Polaris by Admiral Raborn.

Second, an argument was made that liquid-fueled rockets gave relatively low initial acceleration, which is disadvantageous in launching a missile from a moving platform in certain sea states.

By mid-July 1956, the Secretary of Defense's Scientific Advisory Committee had recommended that a solid-propellant missile program be fully instigated but not using the unsuitable Jupiter payload and guidance system.

By October 1956, a study group comprising key figures from Navy, industry and academic organizations considered various design parameters of the Polaris system and trade-offs between different sub-sections.

Ongoing problems with the W-47 warhead, especially with its mechanical arming and safing equipment, led to large numbers of the missiles being recalled for modifications, and the U.S. Navy sought a replacement with either a larger yield or equivalent destructive power.

Waves and swells rocking the boat or submarine, as well as possible flexing of the ship's hull, had to be taken into account to properly aim the missile.

The launch of a second Russian satellite and pressing public and government opinions caused Secretary Wilson to move the project along more quickly.

Developed by the Autonetics Division of North American Aviation for the U.S. Air Force Navaho, the XN6 was a system designed for air-breathing cruise missiles, but by 1958 had proved useful for installment on submarines.

Two American physicists at Johns Hopkins's Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), William Guier and George Weiffenbach, began this work in 1958.

The initial test model of the Polaris was referred to as the AX series and made its maiden flight from Cape Canaveral on September 24, 1958.

When the final AX flight was conducted a year after the program began, 17 Polaris missiles had been flown of which five met all of their test objectives.

The two-stage solid propellant missile had a length of 28.5 ft (8.7 m), a body diameter of 54 inches (1.4 m), and a launch weight of 28,800 pounds (13,100 kg).

Work on its W47 nuclear warhead began in 1957 at the facility that is now called the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory by a team headed by John Foster and Harold Brown.

They were mostly useful for attacking dispersed military surface targets (airfields or radar sites), clearing a pathway for heavy bombers, although in the general public perception Polaris was a strategic second-strike retaliatory weapon.

To obtain the major gains in performance of the Polaris A3 in comparison to early models, there were many improvements, including propellants and material used in the construction of the burn chambers.

The A-3 featured multiple re-entry vehicles (MRVs) which spread the warheads about a common target, and the B-3 was to have penetration aids to counter Soviet Anti-Ballistic Missile defenses.

Under the agreement, the United Kingdom paid an additional 5% of their total procurement cost of 2.5 billion dollars to the U.S. government as a research and development contribution.

The main aim is to replace obsolete components at minimal cost by using commercial off the shelf (COTS) hardware; all the while maintaining the demonstrated performance of the existing Trident II missiles.

It began in 1985 in response to concerns that the supply of surplus Minuteman I boosters used to launch targets and other experiments on intercontinental ballistic missile flight trajectories in support of the Strategic Defense Initiative would be depleted by 1988.

[28] In return, the British agreed to assign control over their Polaris missile targeting to the SACEUR (Supreme Allied Commander, Europe), with the provision that in a national emergency when unsupported by the NATO allies, the targeting, permission to fire, and firing of those Polaris missiles would reside with the British national authorities.

When replaced by the Chevaline warhead, the sum total of deployed RVs and warheads was reduced to three boatloads.The original U.S. Navy Polaris had not been designed to penetrate anti-ballistic missile (ABM) defenses, but the Royal Navy had to ensure that its small Polaris force operating alone, and often with only one submarine on deterrent patrol, could penetrate the ABM screen around Moscow.

Various aspects of the Polaris, such as increasing deployment efficiency and creating ways to improve the penetrative power were specific items considered in the tests conducted during the Antelope program.

[28] The Ministry of Defence upgraded its nuclear missiles to the longer-ranged Trident after much political wrangling within the Callaghan Labour Party government over its cost and whether it was necessary.

Consequently, many spare parts and repair facilities for the Polaris that were located in the U.S. ceased to be available (such as at Lockheed, which had moved on first to the Poseidon and then to the Trident missile).

During its reconstruction program in 1957–1961, the Italian cruiser Giuseppe Garibaldi was fitted with four Polaris missile launchers located in the aft part of the ship.

The Joint Congressional Committee report on Atomic Energy accentuated the three previous factors in Italy's decision to switch to the Polaris missiles.