Polio vaccine

[27] A novel OPV2 vaccine (nOPV2) which has been genetically modified to reduce the likelihood of disease-causing activating mutations was granted emergency licencing in 2021, and subsequently full licensure in December 2023.

Signs and symptoms of an allergic reaction, which usually appear within minutes or a few hours after receiving the injected vaccine, include breathing difficulties, weakness, hoarseness or wheezing, heart rate fluctuations, skin rash, and dizziness.

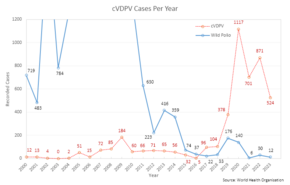

[33] The Sabin OPV results in vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) in approximately one individual per every 2.7 million doses administered, with symptoms identical to wild polio.

[36] More recently, the virus was found in certain forms of cancer in humans, for instance brain and bone tumors, pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma, and some types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

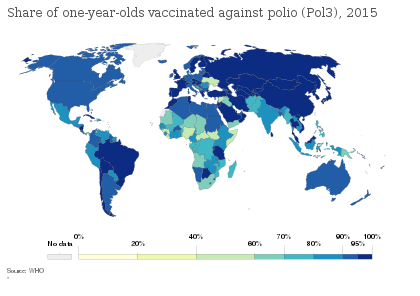

[49] The disease has since resurged in Nigeria and in several other African nations without necessary information, which epidemiologists believe is due to refusals by certain local populations to allow their children to receive the polio vaccine.

Large-scale clinical trials performed in the Soviet Union in the late 1950s to early 1960s by Mikhail Chumakov and his colleagues demonstrated the safety and high efficacy of the vaccine.

[51] The primary attenuating factor common to all three Sabin vaccines is a mutation located in the virus's internal ribosome entry site,[56] which alters stem-loop structures and reduces the ability of poliovirus to translate its RNA template within the host cell.

The development of immunity to polio efficiently blocks person-to-person transmission of wild poliovirus, thereby protecting both individual vaccine recipients and the wider community.

This virus was also notable for primarily impacting affluent children, making it a prime target for vaccine development, despite its relatively low mortality and morbidity.

[61] Despite this, the community of researchers in the field thus far had largely observed an informal moratorium on any vaccine development as it was perceived to present too high a risk for too little likelihood of success.

[62][63] This shifted in the early 1930s when American groups took up the challenge: Maurice Brodie led a team from the public health laboratory of the city of New York and John A. Kolmer collaborated with the Research Institute of Cutaneous Medicine in Philadelphia.

The rivalry between these two researchers lent itself to a race-like mentality which, combined with a lack of oversight of medical studies, was reflected in the methodology and outcomes of each of these early vaccine development ventures.

[66] Using methods of production that were later described as "hair-raisingly amateurish, the therapeutic equivalent of bath-tub gin,"[67] Kolmer ground the spinal cords of his infected monkeys and soaked them in a salt solution.

He then filtered the solution through mesh, treated it with ricinolate, and refrigerated the product for 14 days[64] to ultimately create what would later be prominently critiqued as a "veritable witches brew".

[69] He also reported that together the Research Institute of Cutaneous Medicine and the Merrell Company of Cincinnati (the manufacturer who held the patent for his ricinoleating process) had distributed 12,000 doses of vaccine to some 700 physicians across the United States and Canada.

[70] At nearly the same time as Kolmer's project, Maurice Brodie had joined immunologist William H. Park at the New York City Health Department where they worked together on poliovirus.

With the aid of grant funding from the President's Birthday Ball Commission (a predecessor to what would become the March of Dimes), Brodie was able to pursue the development of an inactivated or "killed virus" vaccine.

[69] Additionally, a polio epidemic in Raleigh, North Carolina provided an opportunity for the U.S. Public Health Service to conduct a highly structured trial of the Brodie vaccine using funding from the Birthday Ball Commission.

[62] As Rivers recalled in his oral history, "All hell broke loose, and it seemed as if everybody was trying to talk at the same time...Jimmy Leake used the strongest language that I have ever heard used at a scientific meeting.

[75] However, when three children became ill with paralytic polio following a dose of the vaccine, the directors of the Warm Springs Foundation in Georgia (acting as the primary funders for the project) requested it be withdrawn in December 1935.

[69][70] While Brodie had arguably made the most progress in the pursuit of a poliovirus vaccine, he suffered the most significant career repercussions due to his status as a less widely known researcher.

[73] Modern researchers recognize that Brodie may well have developed an effective polio vaccine, however, the basic science and technology of the time were insufficient to understand and utilize this breakthrough.

[66][62][70][76] A breakthrough came in 1948 when a research group headed by John Enders at the Children's Hospital Boston successfully cultivated the poliovirus in human tissue in the laboratory.

[43][82] The first effective polio vaccine was developed in 1952 by Jonas Salk and a team at the University of Pittsburgh that included Julius Youngner, Byron Bennett, L. James Lewis, and Lorraine Friedman, which required years of subsequent testing.

Salk went on CBS radio to report a successful test on a small group of adults and children on 26 March 1953; two days later, the results were published in JAMA.

[43] The results of the field trial were announced on 12 April 1955 (the tenth anniversary of the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose paralytic illness was generally believed to have been caused by polio).

[94] In response, the Surgeon General pulled all polio vaccines made by Cutter Laboratories from the market, but not before 260 cases of paralytic illness had occurred.

During a meeting in Stockholm to discuss polio vaccines in November 1955, Sabin presented results obtained on a group of 80 volunteers, while Koprowski read a paper detailing the findings of a trial enrolling 150 people.

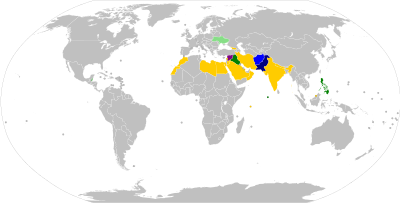

[111] As of 2014, polio virus had spread to 10 countries, mainly in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, with Pakistan, Syria, and Cameroon advising vaccinations to outbound travellers.

On 11 September 2016, two unidentified gunmen associated with the Pakistani Taliban, Jamaat-ul-Ahrar, shot Zakaullah Khan, a doctor who was administering polio vaccines in Pakistan.