Cipher Bureau (Poland)

Five weeks before the outbreak of World War II, on 25 July 1939, in Warsaw, the Polish Cipher Bureau revealed its Enigma-decryption techniques and equipment to representatives of French and British military intelligence, which had been unable to make any headway against Enigma.

This Polish intelligence-and-technology transfer would give the Allies an unprecedented advantage (Ultra) in their ultimately victorious prosecution of World War II.

[4]) During the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921), approximately a hundred Russian ciphers were broken by a sizable cadre of Polish cryptologists who included army Lieutenant Jan Kowalewski and three world-famous professors of mathematics – Stefan Mazurkiewicz, Wacław Sierpiński, and Stanisław Leśniewski.

The Poles were able to follow the whole operation of Budionny's Cavalry Army in the second half of August 1920 with incredible precision, just by monitoring his radiotelegraphic correspondence with Tukhachevsky, including the famous and historic conflict between the two Russian commanders.

His insistent demands alerted the customs officials, who notified the Polish General Staff's Cipher Bureau, which took a keen interest in new developments in radio technology.

[15] In September 1932, Maksymilian Ciężki hired three young graduates of the Poznań course to be Bureau staff members: Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski.

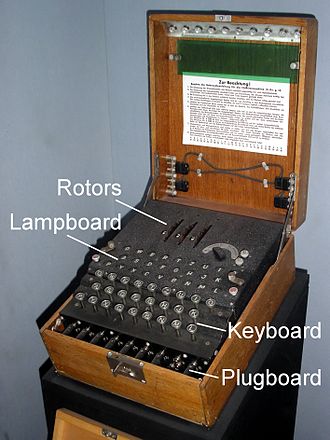

[17] In December 1932, Marian Rejewski made what historian David Kahn describes as one of the greatest advances in cryptologic history, by applying pure mathematics – the theory of permutations and groups – to breaking the German armed forces' Enigma machine ciphers.

Henryk Zygalski devised a manual method that used 26 perforated sheets, and Marian Rejewski commissioned the AVA company to produce the bomba kryptologiczna (cryptologic bomb).

[35] Until 1937 the Cipher Bureau's German section, BS-4, had been housed in the Polish General Staff building – the stately 18th-century "Saxon Palace" – in Warsaw.

Strolling agents, even if lacking access to the Staff building, could observe personnel entering and leaving, and photograph them with concealed miniature cameras.

Annual Abwehr intelligence assignments for German agents in Warsaw placed a priority on securing informants at the Polish General Staff.

[36] It was in the Kabaty Woods, at Pyry, on 25 and 26[d] July 1939, with war looming, that, on instructions from the Polish General Staff, the Cipher Bureau's chiefs, Lt. Col. Gwido Langer and Major Maksymilian Ciężki, the three civilian mathematician-cryptologists, and Col. Stefan Mayer, chief of intelligence, revealed Poland's achievements to cryptanalytical representatives of France and Britain, explaining how they had broken Enigma.

Former Bletchley Park mathematician-cryptologist Gordon Welchman later wrote: "Ultra would never have gotten off the ground if we had not learned from the Poles, in the nick of time, the details both of the German military ... Enigma machine, and of the operating procedures that were in use.

[43] British prime minister Winston Churchill's greatest wartime fear, even after Hitler had suspended Operation Sea Lion and invaded the Soviet Union, was that the German submarine wolfpacks would succeed in strangling sea-locked Britain.

[45] Had Britain capitulated to Hitler, the United States would have been deprived of an essential forward base for its subsequent involvement in the European and North African theaters.

[47] On 5 September 1939, as it became clear that Poland was unlikely to halt the ongoing German invasion, BS-4 received orders to destroy part of its files and evacuate essential personnel.

[49] At PC Bruno, outside Paris, on 20 October 1939 the Poles resumed work on German Enigma ciphers in close collaboration with Britain's Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park.

[51] As late as December 1939, when Lt. Col. Gwido Langer, accompanied by Captain Braquenié, visited London and Bletchley Park, the British asked that the Polish cryptologists be turned over to them.

Before fighting had started in Norway in April 1940, the Polish-French team solved an uncommonly hard three-letter code used by the Germans to communicate with fighter and bomber squadrons and for exchange of meteorological data between aircraft and land.

The Germans' carelessness meant that now the Poles, having after midnight solved Enigma's daily setting, could with no further effort also read the Luftwaffe signals.

[58][f] The Germans, just before opening their 10 May 1940 offensive in the west that would trample Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands in order to reach the borders of France, once again changed their procedure for enciphering message keys, rendering the Zygalski sheets "completely useless"[59][60] and temporarily defeating the joint British–Polish cryptologic attacks on Enigma.

[63] Over the two years since its establishment in October 1940, Cadix had decrypted thousands of Wehrmacht, SS and Gestapo messages, originating not only from French territory but from across Europe, which provided invaluable intelligence to Allied commands and resistance movements.

[65] Having departed Cadix, the Polish personnel evaded the occupying Italian security police and German Gestapo and sought to escape France via Spain.

[66] Jerzy Różycki, Jan Graliński and Piotr Smoleński had died in the January 1942 sinking, in the Mediterranean Sea, of a French passenger ship, the SS Lamoricière, in which they had been returning to southern France from a tour of duty in Algeria.

[71] Finally, with the end of the two mathematicians' cryptologic work at the close of World War II, the Cipher Bureau ceased to exist.

From nearly its inception in 1931 until war's end in 1945, the Bureau, sometimes incorporated into aggregates under cryptonyms (PC Bruno and Cadix), had been essentially the same agency, with most of the same core personnel, carrying out much the same tasks; now it was extinguished.

Cadix's Polish military chiefs, Langer and Ciężki, had also been captured—by the Germans, as they tried to escape from France into Spain on the night of 10–11 March 1943—along with three other Poles: Antoni Palluth, Edward Fokczyński and Kazimierz Gaca.

[75] Despite the varyingly dire circumstances in which they were held, none of them—Stefan Mayer emphasizes—betrayed the secret of Enigma's decryption, thus making it possible for the Allies to continue exploiting this vital intelligence resource.

[76] Before the war, Palluth, a lecturer in the 1929 secret Poznań University cryptology course, had been co-owner of AVA, which produced equipment for the Cipher Bureau, and knew many details of the decryption technology.

[79] The 1979 Polish film Sekret Enigmy (The Enigma Secret)[80][better source needed] is a generally fair, if superficial, account of the Cipher Bureau's story.