Rotor machine

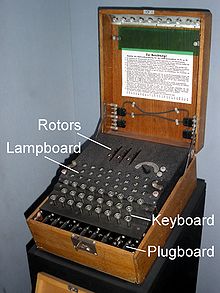

The most famous example is the German Enigma machine, the output of which was deciphered by the Allies during World War II, producing intelligence code-named Ultra.

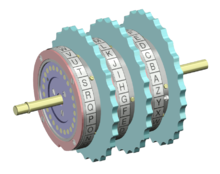

By this means, a rotor machine produces a complex polyalphabetic substitution cipher, which changes with every key press.

In classical cryptography, one of the earliest encryption methods was the simple substitution cipher, where letters in a message were systematically replaced using some secret scheme.

Monoalphabetic substitution ciphers used only a single replacement scheme — sometimes termed an "alphabet"; this could be easily broken, for example, by using frequency analysis.

The invention of rotor machines mechanised polyalphabetic encryption, providing a practical way to use a much larger number of alphabets.

Enigma, and the rotor machines generally, were just what was needed since they were seriously polyalphabetic, using a different substitution alphabet for each letter of plaintext, and automatic, requiring no extraordinary abilities from their users.

Although the key itself (mostly hidden in the wiring of the rotor) might not be known, the methods for attacking these types of ciphers don't need that information.

[citation needed] The concept of a rotor machine occurred to a number of inventors independently at a similar time.

In 2003, it emerged that the first inventors were two Dutch naval officers, Theo A. van Hengel (1875–1939) and R. P. C. Spengler (1875–1955) in 1915 (De Leeuw, 2003).

Previously, the invention had been ascribed to four inventors working independently and at much the same time: Edward Hebern, Arvid Damm, Hugo Koch and Arthur Scherbius.

Unknown to Hebern, William F. Friedman of the US Army's SIS promptly demonstrated a flaw in the system that allowed the ciphers from it, and from any machine with similar design features, to be cracked with enough work.

The most widely known rotor cipher device is the German Enigma machine used during World War II, of which there were a number of variants.

Scherbius joined forces with a mechanical engineer named Ritter and formed Chiffriermaschinen AG in Berlin before demonstrating Enigma to the public in Bern in 1923, and then in 1924 at the World Postal Congress in Stockholm.

In 1927 Scherbius bought Koch's patents, and in 1928 they added a plugboard, essentially a non-rotating manually rewireable fourth rotor, on the front of the machine.

However, the German armed forces, responding in part to revelations that their codes had been broken during World War I, adopted the Enigma to secure their communications.

The Enigma (in several variants) was the rotor machine that Scherbius's company and its successor, Heimsoth & Reinke, supplied to the German military and to such agencies as the Nazi party security organization, the SD.

On July 25, 1939, just five weeks before Hitler's invasion of Poland, the Polish General Staff's Cipher Bureau shared its Enigma-decryption methods and equipment with the French and British as the Poles' contribution to the common defense against Nazi Germany.

During World War II (WWII), both the Germans and Allies developed additional rotor machines.

A unique rotor machine called the Cryptograph was constructed in 2002 by Netherlands-based Tatjana van Vark.

A software implementation of a rotor machine was used in the crypt command that was part of early UNIX operating systems.