Political polarization in the United States

Partisans performed much more poorly when asked to evaluate data that challenged their pre-existing views about gun control laws; moreover, high mathematical skill levels did not prevent this.

[36] In the 1990s, House Speaker Newt Gingrich's use of "asymmetric constitutional hardball" led to increasing polarization in American politics driven primarily by the Republican Party.

After President George W. Bush barely won reelection in 2004, English historian Simon Schama noted that the US had not been so polarized since the American Civil War, and that a more apt name might be the Divided States of America.

Since 2011, both parties have gradually placed economic stimulation and job growth lower on their priority list, with Democrats experiencing a sharper decline of importance when compared to Republicans.

[53] The study continues to explain that, when considering geographic location, because individuals in conservative and right leaning areas are more likely to see COVID-19 as a non-threat, they are less likely to stay home and follow health guidelines.

Several institutional and structural features of the American electoral system contribute to elite-driven polarization, by selecting more ideologically extreme candidates and rewarding antagonistic legislative behavior over compromise.

Some, such as Washington Post opinion writer Robert Kaiser, argued this allowed wealthy people, corporations, unions, and other groups to push the parties' policy platforms toward ideological extremes, resulting in a state of greater polarization.

According to political scientists Matt Grossmann and David A. Hopkins, the Republican Party's gains among white voters without college degrees contributed to the rise of right-wing populism.

[108][109] The argument that redistricting, through gerrymandering, would contribute to political polarization is based on the idea that new non-competitive districts created would lead to the election of extremist candidates representing the supermajority party, with no accountability to the voice of the minority.

However, more partisan media pockets have emerged in blogs, podcasts, talk radio, websites, and cable news channels, which are much more likely to use insulting language, mockery, and extremely dramatic reactions, collectively referred to as "outrage".

[116] A 2020 paper comparing polarization across several wealthy countries found no consistent trend,[117] prompting Ezra Klein to reject the theory that the Internet and social media were the underlying cause of the increase in the United States.

[118][120] Haidt and Lukianoff argue that the filter bubbles created by the News Feed algorithm of Facebook and other social media platforms are also one of the principal factors amplifying political polarization since 2000 (when a majority of U.S. households first had at least one personal computer and then internet access the following year).

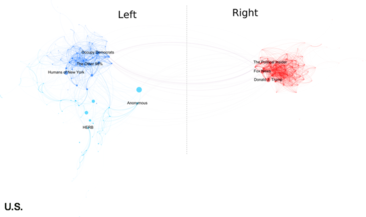

"[131] According to a report by Oxford by researchers including sociologist Philip N. Howard, social media played a major role in political polarization in the United States, due to computational propaganda -- "the use of automation, algorithms, and big-data analytics to manipulate public life"—such as the spread of fake news and conspiracy theories.

"[132] Sarah Kreps of Brookings Institution argue that in the wake of foreign influence operations which are nothing new but boosted by digital tools, the U.S. has had to spend exorbitantly on defensive measures "just to break even on democratic legitimacy.

According to committee chair Adam Schiff, "[The Russian] social media campaign was designed to further a broader Kremlin objective: sowing discord in the U.S. by inflaming passions on a range of divisive issues.

The Russians did so by weaving together fake accounts, pages, and communities to push politicized content and videos, and to mobilize real Americans to sign online petitions and join rallies and protests.

For the politicians, it creates an artificial environment where their positions appear uniformly popular and opposing views are angrily denounced, making compromise seem risky.

[139][140][141] According to Jonathan Hopkin, decades of neoliberal policies, which made the United States "the most extreme case of the subjection of society to the brute force of the market," resulted in unprecedented levels of inequality, and combined with an unstable financial system and limited political choices, paved the way for political instability and revolt, as evidenced by the resurgence of the American left as represented by Bernie Sanders 2016 presidential campaign and the rise of an "unlikely figure" like Donald Trump to the presidency of the United States.

[143] Potentially both a cause and effect of polarization is "demonization" of political opponents, such as accusing them not just of being wrong about certain legislation or policies but of hating their country, or the use of what are called ‘devil terms’ — defined by communications professor Jennifer Mercieca as “things that are so unquestionably bad that you can’t have a debate about them”.

[144] Some examples include the accusations that President Biden has a plan, to “flood our country with terrorists, fentanyl, child traffickers, and MS-13 gang members", and that "Under President Biden's leadership ... We face an unprecedented assault on the American way of life by the radical left" (Mary E. Miller-IL), that “Democrats are so enamored of power that they want to legalize cheating in elections,” (Andy Biggs-AZ), "America-hating Socialists seek to upend the American way of life based on freedom and liberty and replace it with dictatorial government that controls every aspect of our lives" (Mo Brooks-AL).

An example of the escalation in aggressive attack is Republican House leader Kevin McCarthy, who after the January 6 insurrection "implored members of his party to tone down their speech", saying, 'We all must acknowledge how our words have contributed to the discord in America ... No more name calling, us versus them.

[34] For instance, Rachel Kleinfeld, an expert on the rule of law and post-conflict governance, writes that political violence is extremely calculated and, while it may appear "spontaneous," it is the culmination of years of "discrimination and social segregation."

[171] As Mann and Ornstein argue, political polarization and the proliferation of media sources have "reinforce[d] tribal divisions, while enhancing a climate where facts are no longer driving the debate and deliberation, nor are they shared by the larger public.

There is a long-standing belief that exposure to both sides of an argument will moderate political attitudes, and there is empirical evidence that voters often do self-moderate, saying that internet users do also search for news in the opposing viewpoint.

"[162] It also influences the politics of senatorial advice and consent, giving partisan presidents the power to appoint judges far to the left or right of center on the federal bench, obstructing the legitimacy of the judicial branch.

[158] Polarization can generate strong partisan critiques of federal judges, which can damage the public perception of the justice system and the legitimacy of the courts as nonpartisan legal arbiters.

First, when the United States conducts relations abroad and appears divided, allies are less likely to trust its promises, enemies are more likely to predict its weaknesses, and uncertainty as to the country's position in world affairs rises.

[192] Elaine Kamarck of the Brookings Institution suggest ways to work within the two-party system, such as taking measures to increase voter turnout to elect more moderate representatives in Congress.

[194] Advocates for setting fixed terms for selection of the justices of the Supreme Court of the United States argue it will reduce the partisanship of confirmation battles if both major parties are satisfied they will have the chance to make a certain number of appointments.

[195] Assemblies create a space where representatives and citizens are encouraged to discuss political topics and issues in a constructive fashion, hopefully resulting in compromise or mutual understanding.