Politics of Wales

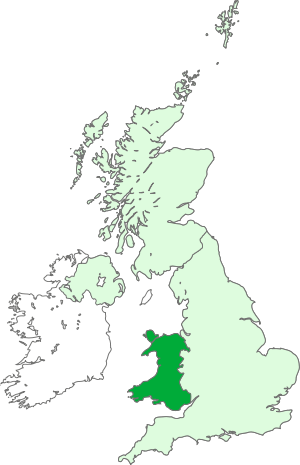

Charles III Heir Apparent William, Prince of Wales First Minister (list) Rt Hon Eluned Morgan MS (L) Deputy First Minister Huw Irranca-Davies MS (L) Counsel General-designate – Elisabeth Jones Chief Whip and Trefnydd – Jane Hutt MS (L) Permanent Secretary Sixth Senedd Llywydd (Presiding Officer) Elin Jones MS (PC) Leader of the Opposition Darren Millar MS (C) Shadow Cabinet Prime Minister Rt Hon Keir Starmer MP (L) Secretary of State for Wales Rt Hon Jo Stevens MP (L) Principal councils (leader list) Corporate Joint Committees Local twinning see also: Regional terms and Regional economy United Kingdom Parliament elections European Parliament elections (1979–2020) Local elections Police and crime commissioner elections Referendums Politics in Wales forms a distinctive polity in the wider politics of the United Kingdom, with Wales as one of the four constituent countries of the United Kingdom (UK).

Under a system of devolution adopted in the late 1990s three of the four countries of the United Kingdom, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, voted for limited self-government, subject to the ability of the UK Parliament in Westminster, nominally at will, to amend, change, broaden or abolish the national governmental systems.

In 2007, the National Assembly for Wales (renamed as the Senedd from May 2020) gained the power to enact Wales-specific Measures.

[2] Owain Glyndwr briefly restored Welsh independence in a national uprising that began in 1400 after his supporters declared him Prince of Wales.

By August 1925 unemployment in Wales rose to 28.5%, in contrast to the economic boom in the early 1920s, rendering constitutional debate an exotic subject.

Further incremental changes also took place, including the establishment of a Digest of Welsh Statistics in 1954, and the designation of Cardiff (Caerdydd) as Wales's capital city in 1955.

[12] In 1964 the incoming Labour Government of Harold Wilson created the Welsh Office under a Secretary of State for Wales, with its powers augmented to include health, agriculture and education in 1968, 1969 and 1970 respectively.

[13] Labour's incremental embrace of a distinctive Welsh polity was arguably catalysed in 1966 when Plaid Cymru president Gwynfor Evans won the Carmarthen by-election (although in fact Labour had endorsed plans for an elected council for Wales weeks before the by-election).

However, by 1967 Labour retreated from endorsing home rule mainly because of the open hostility expressed by other Welsh Labour MPs to anything "which could be interpreted as a concession to nationalism" and because of opposition by the Secretary of State for Scotland, who was responding to a growth of Scottish nationalism.

In July 1997, the government published a White Paper, A Voice for Wales, which outlined its proposals for devolution, and in September 1997 an elected Assembly with competence over the Welsh Office's powers was narrowly approved in a referendum.

Labour won the largest share of votes and seats in each election and has always been in government in Wales, either as a minority administration or in coalition, first with the Liberal Democrats (2000 to 2003) and with Plaid Cymru between 2007 and 2011.

[17] Policy divergence between Wales and England has arisen largely because Welsh governments have not followed the market-based English public service reforms introduced during the premiership of Tony Blair.

In 2002, First Minister Rhodri Morgan said that a key theme of the first four years of the Assembly was the creation of a new set of citizenship rights that are free at the point of use, universal and unconditional.

[18] Marking ten years of devolution in a 2009 speech, Morgan highlighted free prescriptions, primary school breakfasts and free swimming as 'Made in Wales' initiatives that had made "a real difference to people’s everyday lives" since the National Assembly came into being.

[19] However, some authors have argued that the approach to public services in England has been more effective than that in Wales, with health and education "cost(ing) less and delivering more".

[17] Unfavourable comparisons between National Health Service waiting lists in England and Wales were a contentious issue in the first and second Assemblies.

[20] Nevertheless, a 'progressive consensus' based on faith in the power of government, universal rather than means-tested services, co-operation rather than competition in public services, a rejection of individual choice as a guide to policy and a focus on equality of outcome continued to underpin the One Wales coalition government in the Third Assembly.

[21] The commitment to universalism may be tested by increasing budgetary constraints; in April 2009 a senior Plaid Cymru adviser warned of impending health and education cuts.

Until May 2007 one important feature of the Assembly was that there was no legal or constitutional separation of the legislative and executive functions, since it was a single corporate entity.

This model of more limited legislative powers is partly because Wales had a more similar legal system to England from 1536, when it was annexed and legally became an integral part of the Kingdom of England (although Wales retained its own judicial system, the Great Sessions, until 1830[43]).

The Assembly inherited the powers and budget of the Secretary of State for Wales and most of the functions of the Welsh Office.

This was significantly enhanced after a referendum in 2011, and the Assembly had primary legislative powers over 20 areas, including Education and Health, from that time.

The lowest tier of local government in Wales is the community council, which is analogous to a civil parish in England.

The Monarch appoints a Lord Lieutenant to represent them in the eight Preserved counties of Wales, which are combinations of council areas.

The Secretary of State for Wales has overall responsibility for the office but it is located administratively within the Department for Constitutional Affairs.

[53] According to Danny Dorling, professor of geography at the Oxford University, "If you look at the more genuinely Welsh areas, especially the Welsh-speaking ones, they did not want to leave the EU.

"[54] The Concordat on Co-ordination of European Union Policy Issues between the UK Government and the devolved administrations notes that "as all foreign policy issues are non-devolved, relations with the European Union are the responsibility of the Parliament and Government of the United Kingdom, as Member State".

Nevertheless, the Welsh Government has deployed their own envoy to America, primarily to promote Wales-specific business interests.

The primary Welsh Government Office is based out of the Washington British Embassy, with satellites in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Atlanta.

Nevertheless, a number of bodies exist across areas including the economy, social issues, housing, research, and more.