Rationing in the United Kingdom

[1][2] At the start of the Second World War in 1939, the United Kingdom was importing 20 million long tons of food per year, including about 70% of its cheese and sugar, almost 80% of fruit and about 70% of cereals and fats.

[3] It was one of the principal strategies of the Germans in the Battle of the Atlantic to attack shipping bound for Britain, restricting British industry and potentially starving the nation into submission.

During the Second World War rationing—not restricted to food—was part of a strategy including controlled prices, subsidies and government-enforced standards, with the goals of managing scarcity and prioritising the armed forces and essential services, and trying to make available to everyone an adequate and affordable supply of goods of acceptable quality.

In line with its business as usual policy during the First World War, the government was initially reluctant to try to control the food markets.

[4] It fought off attempts to introduce minimum prices in cereal production, though relenting in the area of control of essential imports (sugar, meat, and grains).

Bread was subsidised from September that year; prompted by local authorities taking matters into their own hands, compulsory rationing was introduced in stages between December 1917 and February 1918 as Britain's supply of wheat decreased to just six weeks' consumption.

In the event, the trade unions of the London docks organised blockades by crowds, but convoys of lorries under military escort took the heart out of the strike, so that the measures did not have to be implemented.

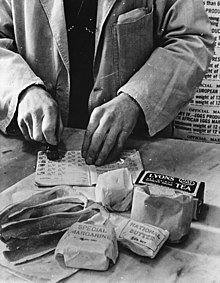

Meat, tea, jam, biscuits, breakfast cereals, cheese, eggs, lard, milk, canned and dried fruit were rationed subsequently, though not all at once.

Lemons and bananas became unobtainable for most of the war; oranges continued to be sold, but greengrocers customarily reserved them for children and pregnant women.

During the war, the Royal Navy requisitioned hundreds of trawlers for military use, leaving primarily smaller vessels thought less likely to be targeted by Axis forces to fish.

[citation needed] Due to the vital role beekeeping played in British agriculture and industry, special allotments of sugar were allowed for each hive.

In addition to rationing and price controls, the government equalised the food supply through subsidies on items consumed by the poor and the working class.

[30] In December 1939, Elsie Widdowson and Robert McCance of the University of Cambridge tested whether the United Kingdom could survive with only domestic food production if U-boats ended all imports.

Two weeks of intensive outdoor exercise simulated the strenuous wartime physical work Britons would likely have to perform.

Britons' actual wartime diet was never as severe as in the Cambridge study because imports from the United States avoided the U-boats,[31] but rationing improved the health of British people; infant mortality declined and life expectancy rose, excluding deaths caused by hostilities.

[29][32] Blackcurrant syrup and later American bottled orange juice was provided free for children under 2, and those under 5 and expectant mothers got subsidised milk.

Following the depletion of raw materials and redirection of labour towards wartime manufactures (such as uniforms),[40] alongside rising inflation, and the inclusion of purchase tax on clothing in October 1940, prices of garments and textiles increased.

Government regulation was required in order to ensure the ability to buy clothing was maintained across the civilian population.

[40] Reported in local and national newspapers, clothes rationing came as a surprise to the public, in order to avoid panic-buying.

[46] Manual workers, civilian uniform wearers, diplomats, performers and new mothers also received extra coupons.

Garments of the same description but different quality would have different prices but require the same number of coupons; the more affordable clothing would often be less robust and wear out sooner, even with repair.

[45] This, therefore, led the Government to implement the Utility Clothing Scheme in September 1941, which was introduced alongside other measures, such as the civilian population being encouraged to repair and remake old clothes; pamphlets were produced by the Ministry of Information with the slogan "Make Do and Mend" in 1943 which gave ideas and instruction as part of a larger campaign which was put in place through collaboration with voluntary organisations.

From July 1942 until June 1945, the basic ration was suspended completely, with essential-user coupons being issued only to those with official sanction.

In 1944, George Orwell wrote: In Mr Stanley Unwin's recent pamphlet Publishing in Peace and War, some interesting facts are given about the quantities of paper allotted by the Government for various purposes.

Examples included razor blades, baby bottles, alarm clocks, frying pans and pots.

Certain foodstuffs that the average 1940s British citizen would find unusual, for example whale meat and canned snoek fish from South Africa, were not rationed.

[30] At the time, this was presented as necessary to feed people in European areas under British control, whose economies had been devastated by the fighting.

[24]: 264 In the late 1940s, the Conservative Party used and encouraged growing public anger at rationing, scarcity, controls, austerity and government bureaucracy to rally middle-class supporters and build a political comeback that won the 1951 general election.

[70] The rationing never came about, in large part because increasing North Sea oil production allowed the UK to offset much of the lost imports.

By the time of the 1979 energy crisis, the United Kingdom had become a net exporter of oil, so on that occasion the government did not even have to consider petrol rationing.