Pop art

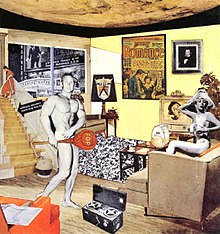

[1][2] The movement presented a challenge to traditions of fine art by including imagery from popular and mass culture, such as advertising, comic books and mundane mass-produced objects.

[2][3] Amongst the early artists that shaped the pop art movement were Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton in Britain, and Larry Rivers, Ray Johnson, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns among others in the United States.

British artists focused on the dynamic and paradoxical imagery of American pop culture as powerful, manipulative symbolic devices that were affecting whole patterns of life, while simultaneously improving the prosperity of a society.

[2][10] They were a gathering of young painters, sculptors, architects, writers and critics who were challenging prevailing modernist approaches to culture as well as traditional views of fine art.

Their group discussions centered on pop culture implications from elements such as mass advertising, movies, product design, comic strips, science fiction and technology.

[6] According to the son of John McHale, the term "pop art" was first coined by his father in 1954 in conversation with Frank Cordell,[12] although other sources credit its origin to British critic Lawrence Alloway.

In any case, sometime between the winter of 1954–55 and 1957 the phrase acquired currency in conversation..."[17] Nevertheless, Alloway was one of the leading critics to defend the inclusion of the imagery of mass culture in the fine arts.

[22] A note about the cover image in January 1958's Art News pointed out that "[Jasper] Johns' first one-man show ... places him with such better-known colleagues as Rauschenberg, Twombly, Kaprow and Ray Johnson".

[10] Rauschenberg, who like Ray Johnson attended Black Mountain College in North Carolina after World War II, was influenced by the earlier work of Kurt Schwitters and other Dada artists, and his belief that "painting relates to both art and life" challenged the dominant modernist perspective of his time.

[24] His use of discarded readymade objects (in his Combines) and pop culture imagery (in his silkscreen paintings) connected his works to topical events in everyday America.

Johns' paintings of flags, targets, numbers, and maps of the U.S. as well three-dimensional depictions of ale cans drew attention to questions of representation in art.

[10] Selecting the old-fashioned comic strip as subject matter, Lichtenstein produces a hard-edged, precise composition that documents while also parodying in a soft manner.

The paintings of Lichtenstein, like those of Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann and others, share a direct attachment to the commonplace image of American popular culture, but also treat the subject in an impersonal manner clearly illustrating the idealization of mass production.

In 1960, Martha Jackson showed installations and assemblages, New Media – New Forms featured Hans Arp, Kurt Schwitters, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Jim Dine and May Wilson.

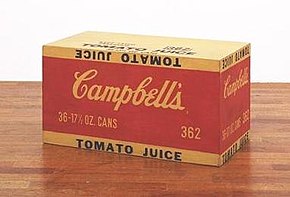

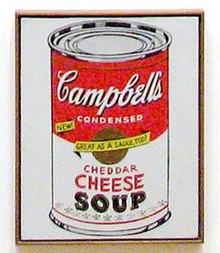

[34][35] Andy Warhol held his first solo exhibition in Los Angeles in July 1962 at Irving Blum's Ferus Gallery, where he showed 32 paintings of Campell's soup cans, one for every flavor.

The cast of colleagues in his performances included: artists Lucas Samaras, Tom Wesselmann, Carolee Schneemann, Öyvind Fahlström and Richard Artschwager; dealer Annina Nosei; art critic Barbara Rose; and screenwriter Rudy Wurlitzer.

The fifty-four artists shown included Richard Lindner, Wayne Thiebaud, Roy Lichtenstein (and his painting Blam), Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Jim Dine, Robert Indiana, Tom Wesselmann, George Segal, Peter Phillips, Peter Blake (The Love Wall from 1961), Öyvind Fahlström, Yves Klein, Arman, Daniel Spoerri, Christo and Mimmo Rotella.

Janis lost some of his abstract expressionist artists when Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Adolph Gottlieb and Philip Guston quit the gallery, but gained Dine, Oldenburg, Segal and Wesselmann.

The show was presented as a typical small supermarket environment, except that everything in it—the produce, canned goods, meat, posters on the wall, etc.—was created by prominent pop artists of the time, including Apple, Warhol, Lichtenstein, Wesselmann, Oldenburg, and Johns.

Pierre Restany wrote the original manifesto for the group, titled the "Constitutive Declaration of New Realism," in April 1960, proclaiming, "Nouveau Réalisme—new ways of perceiving the real.

"[45] This joint declaration was signed on 27 October 1960, in Yves Klein's workshop, by nine people: Yves Klein, Arman, Martial Raysse, Pierre Restany, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tinguely and the Ultra-Lettrists, Francois Dufrêne, Raymond Hains, Jacques de la Villeglé; in 1961 these were joined by César, Mimmo Rotella, then Niki de Saint Phalle and Gérard Deschamps.

However, the Spanish artist who could be considered most authentically part of "pop" art is Alfredo Alcaín, because of the use he makes of popular images and empty spaces in his compositions.

[citation needed] Also in the category of Spanish pop art is the "Chronicle Team" (El Equipo Crónica), which existed in Valencia between 1964 and 1981, formed by the artists Manolo Valdés and Rafael Solbes.

Filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar emerged from Madrid's "La Movida" subculture of the 1970s making low budget super 8 pop art movies, and he was subsequently called the Andy Warhol of Spain by the media at the time.

Kiwiana is a pop-centered, idealised representation of classically Kiwi icons, such as meat pies, kiwifruit, tractors, jandals, Four Square supermarkets; the inherent campness of this is often subverted to signify cultural messages.

The use of images of the modern world, copied from magazines in the photomontage-style paintings produced by Harue Koga in the late 1920s and early 1930s, foreshadowed elements of pop art.

Italian pop art originated in 1950s culture – the works of the artists Enrico Baj and Mimmo Rotella to be precise, rightly considered the forerunners of this scene.

In fact, it was around 1958–1959 that Baj and Rotella abandoned their previous careers (which might be generically defined as belonging to a non-representational genre, despite being thoroughly post-Dadaist), to catapult themselves into a new world of images, and the reflections on them, which was springing up all around them.

Yet this is not an exclusive element; there is a long line of artists, including Gianni Ruffi, Roberto Barni, Silvio Pasotti, Umberto Bignardi, and Claudio Cintoli, who take on reality as a toy, as a great pool of imagery from which to draw material with disenchantment and frivolity, questioning the traditional linguistic role models with a renewed spirit of "let me have fun" à la Aldo Palazzeschi.

By the end of the 1960s and early 1970s, pop art references disappeared from the work of some of these artists when they started to adopt a more critical attitude towards America because of the Vietnam War's increasingly gruesome character.