Popish Plot

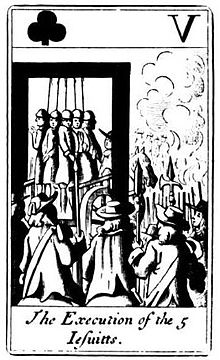

[1] Oates alleged that there was an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate Charles II, accusations that led to the show trials and executions of at least 22 men and precipitated the Exclusion Bill Crisis.

The fictitious Popish Plot must be understood against the background of the English Reformation and the subsequent development of a strong anti-Catholic nationalist sentiment among the mostly Protestant population of England.

The English Reformation began in 1533, when King Henry VIII (1509–1547) sought an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon to marry Anne Boleyn.

Under Henry's son Edward VI (1547–1553), the Church of England was transformed into a strictly Protestant body, with many remnants of Catholicism suppressed.

Mary tainted her policy with two unpopular actions: she married her cousin, King Philip II of Spain, where the Inquisition continued, and had 300 Protestants burned at the stake, causing many Englishmen to associate Catholicism with the involvement of foreign powers and religious persecution.

The magnitude of the plot, meant to kill the leading government figures in one stroke, convinced many Englishmen that Catholics were murderous conspirators who would stop at nothing to have their way, laying the groundwork for future allegations.

Anti-Catholic sentiment was a constant factor in how England perceived the events of the following decades: the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) was seen as an attempt by the Catholic Habsburgs to exterminate German Protestantism.

This, together with accounts of Catholic atrocities in Ireland in 1641, helped trigger the English Civil War (1642–1649), which led to the abolition of the monarchy and a decade of Puritan rule tolerating most forms of Protestantism, but not Catholicism.

Kenyon remarks, "At Coventry, the townspeople were possessed by the idea that the papists were about to rise and cut their throats ... A nationwide panic seemed likely, and as homeless refugees poured out from London into the countryside, they took with them stories of a kind which were to be familiar enough in 1678 and 1679.

In December 1677 an anonymous pamphlet (possibly by Andrew Marvell) spread alarm in London by accusing the Pope of plotting to overthrow the lawful government of England.

Oates and Israel Tonge, a fanatically anti-Catholic clergyman (who was widely believed to be insane), had written a large manuscript that accused the Catholic Church authorities of approving the assassination of Charles II.

[7] Charles was dismissive but Kirkby stated that he knew the names of assassins who planned to shoot the King and, if that failed, the Queen's physician, Sir George Wakeman, would poison him.

At this stage, he was already sceptical, but he was apparently not ready to rule out the possibility that there might be a plot of some sort (otherwise, Kenyon argues, he would not have given these two very obscure men a private audience).

[12] The King had a long and frank talk with Paul Barillon, the French ambassador, in which he made it clear that he did not believe that there was a word of truth in the plot, and that Oates was "a wicked man"; but that by now he had come round to the view that there must be an investigation, particularly with Parliament about to reassemble.

The meeting discussed a variety of methods which included: stabbing by Irish ruffians, shooting by two Jesuit soldiers, or poisoning by the Queen's physician, Sir George Wakeman.

A turning point came when he was shown five letters, supposedly written by well-known priests and giving details of the plot, which he was suspected of forging: Oates "at a single glance" named each of the alleged authors.

At this the council were "amazed" and began to give much greater credence to the plot; apparently it did not occur to them that Oates' ability to recognise the letters made it more likely, rather than less, that he had forged them.

The allegations gained little credence until the murder of Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey, a magistrate and strong supporter of Protestantism, to whom Oates had made his first depositions.

As Kenyon commented, "Next day, the 18th, James wrote to William of Orange that Godfrey's death was already 'laid against the Catholics', and even he, never the most realistic of men, feared that 'all these things happening together will cause a great flame in the Parliament'.

Oates' associate William Bedloe denounced the silversmith Miles Prance, who in turn named three working men, Berry, Green and Hill, who were tried, convicted and executed in February 1679; but it rapidly became clear that they were completely innocent, and that Prance, who had been subjected to torture, named them simply to gain his freedom (Kenyon suggests that he may have chosen men against whom he had a personal grudge, or he may simply have chosen them because they were the first Catholic acquaintances of his who came to mind).

The King dismissed the accusations as absurd, pointing out that Belasyse was so afflicted with gout that he could hardly stand, while Arundell and Stafford, who had not been on speaking terms for 25 years, were most unlikely to be intriguing together; but Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury had the lords arrested and sent to the Tower on 25 October 1678.

Seizing upon the anti-Catholic tide, Shaftesbury publicly demanded that the King's brother, James, be excluded from the royal succession, prompting the Exclusion crisis.

On 10 April 1679 Arundell and three of his companions (Belasyse was too ill to attend) were brought to the House of Lords to put in pleas against the articles of impeachment.

Stafford, denied the services of counsel, failed to exploit several inconsistencies in Tuberville's testimony, which a good lawyer might have turned to his client's advantage.

[21] On 24 November 1678, Oates claimed the Queen was working with the King's physician to poison him and enlisted the aid of "Captain" William Bedloe, a notorious member of the London underworld.

William Staley, a young Catholic banker, made a drunken threat against the King; within 10 days he was tried, convicted of plotting treason and executed.

The public invented their own stories, including a tale that the sound of digging had been heard near the House of Commons and rumours of a French invasion on the Isle of Purbeck.

The King, who was notably tolerant of religious differences and generally inclined to clemency, was embittered at the number of innocent men he had been forced to condemn; possibly thinking of the Indemnity and Oblivion Act 1660 (12 Cha.

On 31 August 1681, Oates was told to leave his apartments in Whitehall, but remained undeterred and even denounced the King and the Duke of York.

John Kenyon points out that European religious orders throughout the Continent were affected since many of them depended on the alms of the English Catholic community for their existence.