Popularity

1800s: Martineau · Tocqueville · Marx · Spencer · Le Bon · Ward · Pareto · Tönnies · Veblen · Simmel · Durkheim · Addams · Mead · Weber · Du Bois · Mannheim · Elias In sociology, popularity is how much a person, idea, place, item or other concept is either liked or accorded status[1][2][3] by other people.

According to psychologist Tessa Lansu at the Radboud University Nijmegen, "Popularity [has] to do with being the middle point of a group and having influence on it.

[7] While popularity is a trait often ascribed to an individual, it is an inherently social phenomenon and thus can only be understood in the context of groups of people.

[8] Notwithstanding the above, popularity as a concept can be applied, assigned, or directed towards objects such as songs, movies, websites, activities, soaps, foods etc.

Individuals who have perceived popularity are often highly socially visible and frequently emulated but rarely liked.

The 3 Factor Model proposed attempts to reconcile the two concepts of sociometric and perceived popularity by combining them orthogonally and providing distinct definitions for each.

According to Freedman, an individual's place in the social landscape is determined by a combination of three factors: what they are; who they are; and the situation.

The Volume-Control Model offers analytical framework to understand how popularity is used to gain political and economic power.

Both popularization and personalization are employed together by tech companies, organizations, governments or individuals as complementing mechanisms to gain economic, political, and social power.

On a sports team, this means that the best players are usually elected captain and in study groups people might be more inclined to like an individual who has a lot of knowledge to share.

[18] Additionally, they are judged to possess many other positive traits such as mental health, intelligence, social awareness, and dominance.

Research shows that attractive people are often perceived to have many positive traits based on nothing other than their looks, regardless of how accurate these perceptions are.

There are two main categories of aggression, relational and overt, both of which have varying consequences for popularity depending on several factors, such as the gender and attractiveness of the aggressor.

For an attractive aggressor however, relational aggression has been found to actually have a positive relationship with perceived popularity.

This peer functioning and gaining popularity is a key player in increasing interest in social networks and groups in the workplace.

To succeed in such a work environment, adults then place popularity as a higher priority than any other goal, even romance.

This acts like Zipf's Law, where the cohesion is a confounding factor that forces the greater links in the smaller minority, causing them to be more noticed and thus more popular.

Additionally, White and Hispanic children were rated as more popular the better they succeeded in school and came from a higher socioeconomic background.

[27] More tasks in the workplace are being done in teams, leading to a greater need of people to seek and feel social approval.

[28][29] Popularity also leads to students in academic environments to receive more help, have more positive relationships and stereotypes, and be more approached by peers.

[31] According to the mere-exposure effect, employees in more central positions that must relate to many others throughout the day, such as a manager, are more likely to be considered popular.

This greatest contribution principle is perceived as a great asset to the team, and members view the leader more favorably and he gains popularity.

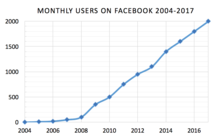

[34] Popularity is a term widely applicable to the modern era thanks primarily to social networking technology.

[37] Experts paid to predict sales often fail but not because they are bad at their jobs; instead, it is because they cannot control the information cascade that ensues after first exposure by consumers.

However, since popularity is primarily constructed as a general consensus of a group's attitude towards something, word-of-mouth is a more effective way to attract new attention.

[42] Popular people may not be those who are best liked interpersonally by their peers, but they do receive most of the positive behavior from coworkers when compared to nonpopular workers.

[citation needed] During interactions with others in the work environment, more popular individuals receive more organizational citizenship behavior (helping and courteousness from others) and less counter productive work behavior (rude reactions and withheld information) than those who are considered less popular in the workplace.

While popularity has proven to be a big determiner of getting more positive feedback and interactions from coworkers, such a quality matters less in organizations where workloads and interdependence is high, such as the medical field.

Attractiveness plays a large role in the workplace and physical appearance influences hiring, whether or not the job might benefit from it.

Because of the prevalence of this problem during the hiring process in all cultures, researchers have recommended training a group to ignore such influencers, just like legislation has worked to control for differences in sex, race, and disabilities.