Populism

[19] As noted by the political scientist Margaret Canovan, "there has been no self-conscious international populist movement which might have attempted to control or limit the term's reference, and as a result those who have used it have been able to attach it a wide variety of meanings.

[22] The political scientist Ben Stanley noted that "although the meaning of the term has proven controversial in the literature, the persistence with which it has recurred suggests the existence at least of an ineliminable core: that is, that it refers to a distinct pattern of ideas.

"[44] Political scientist David Art argues that the concept of populism brings together disparate phenomena in an unhelpful manner, and ultimately obscures and legitimizes figures who are more comprehensively defined as nativists and authoritarians.

[50] Author Thomas Frank has criticized the common use of the term Populism to refer to far-right nativism and racism, noting that the original People's Party was relatively liberal on the rights of women and minorities by the standards of the time.

[58] The political scientist Manuel Anselmi proposed that populism be defined as featuring a "homogeneous community-people" which "perceives itself as the absolute holder of popular sovereignty" and "expresses an anti-establishment attitude.

[80] Populist leaders thus "come in many different shades and sizes" but, according to Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, share one common element: "a carefully crafted image of the vox populi".

[114] The Zambian populist Michael Sata for instance adopted a xenophobic stance during his campaigns by focusing his criticism on the country's Asian minority, decrying Chinese and Indian ownership of businesses and mines.

[123] An example of this populist understanding of the general will can be seen in Chávez's 2007 inaugural address, when he stated that "All individuals are subject to error and seduction, but not the people, which possesses to an eminent degree of consciousness of its own good and the measure of its independence.

[144] Kurt Weyland defined this conception of populism as "a political strategy through which a personalist leader seeks or exercises government power based on direct, unmediated, uninstitutionalized support from large numbers of mostly unorganized followers".

[200] An example of this is Umberto Bossi, the leader of the right-wing populist Italian Lega Nord, who at rallies would state "the League has a hard-on" while putting his middle-finger up as a sign of disrespect to the government in Rome.

[199] In South Africa, the populist Julius Malema and members of his Economic Freedom Fighters attended parliament dressed as miners and workers to distinguish themselves from the other politicians wearing suits.

[204] Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser noted that "in reality, most populist leaders are very much part of the national elite", typically being highly educated, upper-middle class, middle-aged males from the majority ethnicity.

[212] Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser suggested that populist personalist leadership was more common in countries with a presidential system rather than a parliamentary one because these allow for the election of a single individual to the role of head of government without the need for an accompanying party.

[244] These could improve political participation among poorer sectors of Venezuelan society, although also served as networks through which the state transferred resources to those neighbourhoods which produced high rates of support for Chavez government.

[257] For this reason, some democratic politicians have argued that they need to become more populist: René Cuperus of the Dutch Labour Party for instance called for social democracy to become "more 'populist' in a leftist way" in order to engage with voters who felt left behind by cultural and technological change.

[272] Various mainstream centrist figures, such as Hillary Clinton and Tony Blair, have argued that governments needed to restrict migration to hinder the appeal of right-wing populists utilising anti-immigrant sentiment in elections.

[275] In some cases, when the populists have taken power, their political rivals have sought to violently overthrow them; this was seen in the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt, when mainstream groups worked with sectors of the military to unseat Hugo Chávez's government.

Such actions, Weyland argues, proves that populism is a strategy for winning and exerting state power and stands in tension with democracy and the values of pluralism, open debate, and fair competition.

[299] In 2019, Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart classified over 50 European political parties as "authoritarian-populist" as well as world leaders like Donald Trump, Silvio Berlusconi, Viktor Orbán, Hugo Chávez, Nicolás Maduro, Jair Bolsonaro, Narendra Modi, and Rodrigo Duterte.

In particular, it was during this era that terms such as "people" and "popular sovereignty" became a major part of the vocabulary of insurgent political movements that courted mass support among an expanding electorate by claiming that they uniquely embodied their interests[.]

[314] In the early 20th century, adherents of both Marxism and fascism flirted with populism, but both movements remained ultimately elitist, emphasising the idea of a small elite who should guide and govern society.

[322] Since the late 1980s, populist experiences emerged in Spain around the figures of José María Ruiz Mateos, Jesús Gil and Mario Conde, businessmen who entered politics chiefly to defend their personal economic interests, but by the turn of the millennium their proposals had proved to meet a limited support at the ballots at the national level.

[326] Blair's government also employed populist rhetoric; in outlining legislation to curtail fox hunting on animal welfare grounds, it presented itself as championing the desires of the majority against the upper-classes who engaged in the sport.

[363] They suggested that this was the case because it was a region with a long tradition of democratic governance and free elections, but with high rates of socio-economic inequality, generating widespread resentments that politicians can articulate through populism.

[371] Prominent examples included Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Cristina de Kirchner in Argentina, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua.

In the region, various populist governments took power but were removed soon after: these include the administrations of Joseph Estrada in the Philippines, Roh Moo-hyun in South Korea, Chen Shui-bian in Taiwan, and Thaksin Shinawatra in Thailand.

[396] The rise of populism in Western Europe is, in large part, a reaction to the failure of traditional parties to respond adequately in the eyes of the electorate to a series of phenomena such as economic and cultural globalisation, the speed and direction of European integration, immigration, the decline of ideologies and class politics, exposure of elite corruption, etc.

[398] As private media companies have had to compete against each other, they have placed an increasing focus on scandals and other sensationalist elements of politics, in doing so promoting anti-governmental sentiments among their readership and cultivating an environment prime for populists.

Norris suggests that events such as globalisation, China's membership of the World Trade Organisation and cheaper imports have left the unsecured members of society (low-waged unskilled workers, single parents, the long term unemployed and the poorer white populations) seeking populist leaders such as Donald Trump and Nigel Farage.

[3][407] Using Brexit and Trump's election as examples, Michael Sandel in his 2020 book The Tyranny of Merit argues that populism came out of disenchantment with 'meritocratic' elites ruling over disenchanted working people.

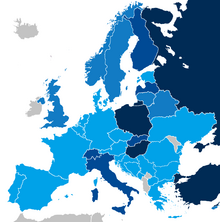

Right-wing populists represented in the parliament

Right-wing populists providing external support for government

Right-wing populists involved in the government

Right-wing populists appoint prime minister/president