Portuguese Inquisition

In 1478, Pope Sixtus IV issued the papal bull Exigit sincerae devotionis affectus that allowed the installation of the Inquisition in Castile, which created a strong wave of immigration of Jews and heretics to Portugal.

[3] On 5 December 1496, as a result of the clause present in his marriage contract with Princess Isabel of Spain, King Manuel I signed an order that forced all Jews to choose between leaving Portugal or converting.

[4] In April 1497, an order was issued for the forcible removal on Easter Sunday of all Jewish sons and daughters under the age of 14 from those Jews who had chosen to leave Portugal rather than convert.

Saraiva tells us that the community of former Jews was on its way to integration when on 9 April 1506 at Lisbon, a mob killed two thousands of New Christians, accused of being the cause of drought and plague that devastated the country.

[8] After the three days massacre, the king punished those responsible and renewed the rights that the Jews had before 1497, giving the New Christians the privilege of not being questioned for their religious practices, and authorizing them to leave Portugal freely.

The basis for Clement VII's decisions was a report that recalled "the true doctrine on the conversion of the Infidels": persuasion and gentleness, following Christ's example.

The report reproduced some information about the workings of the inquisitorial courts, saying the abuses of the inquisitors were such, that it was easy to understand that they were "ministers of Satan and not of Christ", acting like "thieves and mercenaries".

[16] The Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier requested that the Goa Inquisition be set up in a letter dated 16 May 1546 to King John III of Portugal, in order to deal with false converts to Catholicism.

Beyond the Azores, the cult survived in many parts of Brazil (where it was established in the 16th through 18th centuries) and is celebrated today in all Brazilian states except two, as well as in pockets of Portuguese settlers in North America (Canada and USA), mainly among those of Azorean descent.

[27] Egipcíaca was the author of the first book to be written by a black woman in Brazil - entitled Sagrada Teologia do Amor Divino das Almas Peregrinas it detailed her religious visions and prophecies.

[28] The movements and concepts of Sebastianism and of the Fifth Empire were sometimes also targets of the Inquisition (the most intense persecution of Sebastianists being during the Philippine Dynasty, though it lasted beyond then), both considered unorthodox and even heretical.

[citation needed] The financial problems of King Sebastian in 1577 led him, in exchange for a large sum of money, to allow the free departure of New Christians, and to ban the confiscation of property by the Inquisition for 10 years.

His sympathy for the victims of the Holy Office was sharpened by his experience of its "unwholesome prisons", where he wrote that "five unfortunates were not uncommonly placed in a cell nine feet by eleven, where the only light came from a narrow opening near the ceiling, where the vessels were changed only once a week, and all spiritual consolation was denied."

[citation needed] Although officially abolished much later, the Portuguese Inquisition lost some of its strength during the second half of the 18th century under the influence of Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, the Marquis of Pombal (1699-1782), who claimed to be clearly opposed to inquisitorial methods, classing them as acts "against humanity and Christian principles".

[42] The most common accusations were mostly against crypto-judaism, but also against other numerous offences, such as crimes against morality, homosexuality, witchcraft, blasphemy, bigamy, Lutheranism, freemasonry, crypto-mohammedism, criticism of dogmas or the inquisition itself.

The main forms of punishment were the galleys, forced labor, flogging, exiles, confiscations and, as a last resort, the death penalty by fire or garrote.

Under the pretext of salvation of the soul and following divine law, exile was nothing more than the removal of undesirables by the church and the state, forming part of the judicial gears of their power.

[46][44] However, historian António José Saraiva came to the conclusion that, although the confiscated assets legally belonged to the king, they were in fact administered and enjoyed by the inquisitors; after deducting the Inquisition's expenses – salaries, visits, trips, autos de fé, among others – what was left, little or nothing, was handed over to the Royal Treasury.

Before the session, however, the accused was informed that if he died, broke a limb or lost consciousness during the torture, it would only be his fault, since he could have avoided the danger by confessing his offences without delay.

[61][62][63] The most common methods of torture were the strappado, in which the victim's arms were tied behind their back by ropes, and the interrogated person was then suspended in the air by a pulley and suddenly lowered a short distance to the ground;[64] and the rack, in its many variants, in which the body was stretched until it dislocated joints and rendered muscles useless.

After the previous phases of denunciations, arrests, interrogations and torture, the accusation was made by an official of the Holy Office, the Promoter, who acted as an agent of the Inquisition's public prosecution service.

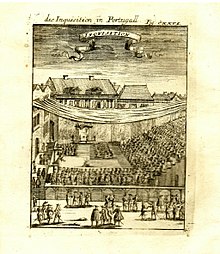

[78][79] Preparations began several weeks in advance, in time to build the scaffold and the amphitheatres, and to make the sanbenitos, a kind of penitential garment the condemned would wear at the auto de fé.

However, the majority of the Goa archives (16,202 trial records) were destroyed and the rest were transported to Brazil, where they can be found in the National Library in Rio de Janeiro.

So, at the conference of the Royal Academy of Portuguese History on 5 January 1721, Father Pedro Monteiro, of the Dominican Order, was entrusted with the task of a study of the Inquisition.

[103] After that, a Historia dos principais actos e procedimentos da Inquisição em Portugal, was published around 1847 anonymously, but later was attributed to Antonio Joaquim Moreira (and José Lourenço de Mendonça).

[106] In more recent times in Portugal, in the 1960s, PIDE (the political police of the right wing Estado Novo) considered banning the António José Saraiva's work on the Portuguese Inquisition.

According to the officer who analysed the book, it didn't make sense to ban it, then in its third edition, but rather to prevent it from being publicised; moreover, the work was found less severe than Alexandre Herculano's, which was much older, on the same subject.

[107] Reflection on the inquisitorial activity of the Catholic Church began in earnest in the run-up to the Great Jubilee of 2000, at the initiative of John Paul II, who called for repentance from "examples of thought and action that are in fact a source of anti-testimony and scandal".

On 12 March 2000, during the celebration of the Jubilee, the Pope John Paul II, on behalf of the entire Catholic Church as well as all Christians, apologised for these acts and in general for several others.

They brought up, among other things, the beatification, at the same time, of Pope Pius IX, notorious for his anti-Semitic views and for the kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara, a six-year-old taken by force from his Jewish family.