Austerity

For example, when an economy is operating at or near capacity, higher short-term deficit spending (stimulus) can cause interest rates to rise, resulting in a reduction in private investment, which in turn reduces economic growth.

[11] The fascist government utilized austerity policies to prevent the democratization of Italy following World War I, with Luigi Einaudi, Maffeo Pantaleoni, Umberto Ricci and Alberto de' Stefani leading this movement.

In such a situation, banks and investors may lose confidence in a government's ability or willingness to pay, and either refuse to roll over existing debts, or demand extremely high interest rates.

[19] Keynesian theory is proposed as being responsible for post-war boom years, before the 1970s, and when public sector investment was at its highest across Europe, partially encouraged by the Marshall Plan.

The approach bunches countries into groups (or "buckets") with similar multiplier values, based on their characteristics, and taking into account the effect of (some) temporary factors such as the state of the business cycle.

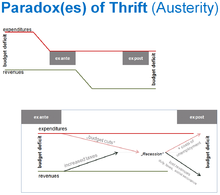

[9] According to economist Martin Wolf, the U.S. and many Eurozone countries experienced rapid increases in their budget deficits in the wake of the 2008 crisis as a result of significant private-sector retrenchment and ongoing capital account surpluses.

[33] Economist Richard Koo described similar effects for several of the developed world economies in December 2011: "Today private sectors in the U.S., the U.K., Spain, and Ireland (but not Greece) are undergoing massive deleveraging [paying down debt rather than spending] in spite of record low interest rates.

With borrowers disappearing and banks reluctant to lend, it is no wonder that, after nearly three years of record low interest rates and massive liquidity injections, industrial economies are still doing so poorly.

"[36] Other anti-austerity economists, such as Seymour[37] have argued that the debate must be reframed as a social and class movement, and its impact judged accordingly, since statecraft is viewed as the main goal.

[47] Economist Martin Wolf analyzed the relationship between cumulative GDP growth in 2008 to 2012 and total reduction in budget deficits due to austerity policies in several European countries during April 2012 (see chart at right).

[48] Similarly, economist Paul Krugman analyzed the relationship between GDP and reduction in budget deficits for several European countries in April 2012 and concluded that austerity was slowing growth.

[56] Keynesian economists and commentators such as Paul Krugman have suggested that this has in fact been occurring, with austerity yielding worse results in proportion to the extent to which it has been imposed.

[65][66] In April and May 2012, France held a presidential election in which the winner, François Hollande, had opposed austerity measures, promising to eliminate France's budget deficit by 2017 by canceling recently enacted tax cuts and exemptions for the wealthy, raising the top tax bracket rate to 75% on incomes over one million euros, restoring the retirement age to 60 with a full pension for those who have worked 42 years, restoring 60,000 jobs recently cut from public education, regulating rent increases, and building additional public housing for the poor.

In the legislative elections in June, Hollande's Socialist Party won a supermajority capable of amending the French Constitution and enabling the immediate enactment of the promised reforms.

[69][70] While Anders Åslund maintains[71] that internal devaluation was not opposed by the Latvian public, Jokubas Salyga has recently chronicled[72] widespread protests against austerity in the country.

The IMF, EU, and other international donors provided substantial financial assistance to Latvia as part of an agreement to defend the currency's peg to the euro in exchange for the government's commitment to stringent austerity measures.

[73] Eighteen months after harsh austerity measures were enacted (including both spending cuts and tax increases),[74] economic growth began to return, although unemployment remained above pre-crisis levels.

Even in Keynesian models, a small open economy can, in the long run, restore full employment through deflation and internal devaluation; the point, however, is that it involves many years of suffering".

In many situations, austerity programs are implemented by countries that were previously under dictatorial regimes, leading to criticism that citizens are forced to repay the debts of their oppressors.

[97][98][99] In 2009, 2010, and 2011, workers and students in Greece and other European countries demonstrated against cuts to pensions, public services, and education spending as a result of government austerity measures.

Opponents point to cases in Ireland and Spain in which austerity measures instituted in response to financial crises in 2009 proved ineffective in combating public debt and placed those countries at risk of defaulting in late 2010.

[104] On 3 February 2015, Joseph Stiglitz wrote: "Austerity had failed repeatedly from its early use under US president Herbert Hoover, which turned the stock-market crash into the Great Depression, to the IMF programs imposed on East Asia and Latin America in recent decades.

[106] According to a 2020 study, which used survey experiments in the UK, Portugal, Spain, Italy and Germany, voters strongly disapprove of austerity measures, in particular spending cuts.

[111] The first study added that "no firm conclusions can be drawn about cause and effect, but the findings back up other research in the field" and campaigners have claimed that cuts to benefits, healthcare and mental health services lead to more deaths including through suicide.

Decisions on future consolidation, tackling the issues that will bring sustained fiscal improvement, create space in the near term for policies that support growth.

[155] An analysis by Hübscher et al. of 166 elections across Europe since 1980 demonstrates that austerity measures lead to increased electoral abstention and a rise in votes for non-mainstream parties, thereby exacerbating political polarization.

[156] A study by Gabriel et al., analyzing elections in 124 European regions from eight countries between 1980 and 2015, found that fiscal consolidations increased the vote share of extreme parties, lowered voter turnout, and heightened political fragmentation.

Notably, after the European debt crisis, a 1% reduction in regional public spending resulted in an approximate 3 percentage point rise in the vote share of extreme parties.

She traces the origins of modern austerity to post-World War I Britain and Italy, when it served as a "powerful counteroffensive" to rising working class agitation and anti-capitalist sentiment.

If the rate is so low that monetary policies cannot mitigate the negative impact of the austerity measures, the significant decrease of tax base makes the revenue of the government and the budget position worse.